Pearl Harbour at 20: Was it really as disastrous as reviews made out, or has it improved with age?

Michael Bay’s 2001 film was savaged by critics when it was released but it wasn’t without merits, writes Geoffrey Macnab

Is it time to cut Michael Bay some slack? To his many detractors, the American director is an abominable figure, a purveyor of macho, explosive and inane movies that are as noisy as they are incomprehensible. Reviewers, though, rarely give him an even break.

Twenty years ago, when Bay’s three-hour Second World War epic Pearl Harbour (2001) was first released in cinemas, many critics agreed that this was among the very worst films they had seen.

“Forty minutes of redundant special effects, surrounded by a love story of stunning banality … directed without grace, vision, or originality,” leading US critic Roger Ebert pronounced.

“A bomb, make no mistake,” the New York Daily News concurred. The film was described as “blockheaded and hollow-hearted”. Watching it was likened to having “a large, pointy lump of rock drop on your head”.

With a reported budget of $145m, Bay’s Disney-backed folly cost less than James Cameron’s $200m Titanic (1997), made for Fox and Paramount, but it was still then the most expensive film financed by a single studio. It wasn’t a Pixar cartoon or part of a franchise but a live-action, character-driven drama about a real historical event which had been a disaster for the US. The young actors, Ben Affleck, Josh Hartnett and Kate Beckinsale, weren’t household names.

Hollywood was already changing when Bay embarked on Pearl Harbour. The first Harry Potter movie came out in the same year. The original X-Men had been released the previous summer. Kevin Feige, creator of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the figure who was to dominate blockbuster moviemaking over the next two decades, was just beginning his producing career in earnest. Bay’s producer Jerry Bruckheimer was shortly to step aboard the even more expensive but wildly successful Pirates of the Caribbean pictures.

Never again after Pearl Harbour would a big studio spend so much money on such a downbeat project. For Bay, though, this was one from the heart. He had listened to the tearful reminiscences of survivors and was determined to honour the memories of those who had died. He talked about his sense of mission. The director of Bad Boys, The Rock and Armageddon was trying to give the audience “the overall essence of the attack on Pearl Harbour”.

Producer Bruckheimer was taking the project equally seriously. “More than anybody, Jerry understood what was owed to the people who actually experienced this Pearl Harbour,” Affleck said of him. “I think he really cared that this be done in the right way and not be a fast-food movie. He wanted it to be resonant and significant.”

As such remarks attest, Pearl Harbour was a strange endeavour: a summer blockbuster that set out to satisfy survivors, military buffs and historians while entertaining a mass audience.

For most younger cinema goers, the events in Hawaii on that December Sunday morning in 1941 had no resonance whatsoever. However, thanks to the efforts of Bay and Bruckheimer, they were about to live through it. The Japanese attack on the US fleet lasted less than two hours – in other words, it was over considerably quicker than Bay’s movie.

Bay and his screenwriter Randall Wallace created characters based on real-life prototypes. Wallace also came up with the fictional conceit of two childhood friends from rural Tennessee who go on to join the US army air corps. Rafe (Ben Affleck) and Danny (Josh Hartnett) are best buddies who’ll do anything for each other, clean-cut all-American heroes.

Two decades on, the storytelling still creaks. We know from the outset that the Japanese are coming. To provide a focus beyond US navy ships being sunk and Americans dying, the filmmakers throw in an absurd love triangle drama. Rafe and Danny both fall in love with a beautiful nurse, Evelyn (Kate Beckinsale).

Rafe begins an affair with her but joins the Eagle Squadron, an American outfit fighting with the RAF during the Battle of Britain. When his plane is shot down, he’s presumed dead. That is the cue for Danny to make his move on Evelyn. Rafe, though, is very much alive, and when he returns he is appalled to find that his best friend has taken his girl. The pals are briefly estranged although it is very obvious they are at least as besotted with each other as with the lustrous-haired nurse.

Bay gives his young leads an incongruously glamorous sheen. Whether it’s a scene in which Evelyn is sticking a syringe in Rafe’s butt or the moments when the pilots are drinking shots together, the actors always have a glossy, luminous look, as if they are models in a department store catalogue.

“The idea was to make the kind of movie that could have been released in the Forties – unironic, slightly naïve – with new technology,” Affleck told GQ. But in trying to portray a lost world of innocence, Pearl Harbour risked seeming simple-minded rather than evocative. Affleck and Hartnett presented an absurdly idealised picture of American masculinity. They were cocky but squeaky clean.

Many have compared Pearl Harbour, unfavourably, with Fred Zinnemann’s James Jones adaptation, From Here to Eternity (1953), also set in the build up to the attack. Whereas Bay made Hawaii look like a sun-drenched holiday camp, Zinnemann deliberately shot in black and white and took a very downbeat approach. He made military life seem tough and tedious. There was homesickness, heavy drinking, infidelity and bullying. In Zinnemann’s film, lonely, introspective soldiers like Montgomery Clift’s Prewitt are a world away from the self-confident jocks played by Affleck and Hartnett.

Pearl Harbour may have won an Oscar for sound editing but its heavy-handed use of music ranges from the maudlin to the bombastic.

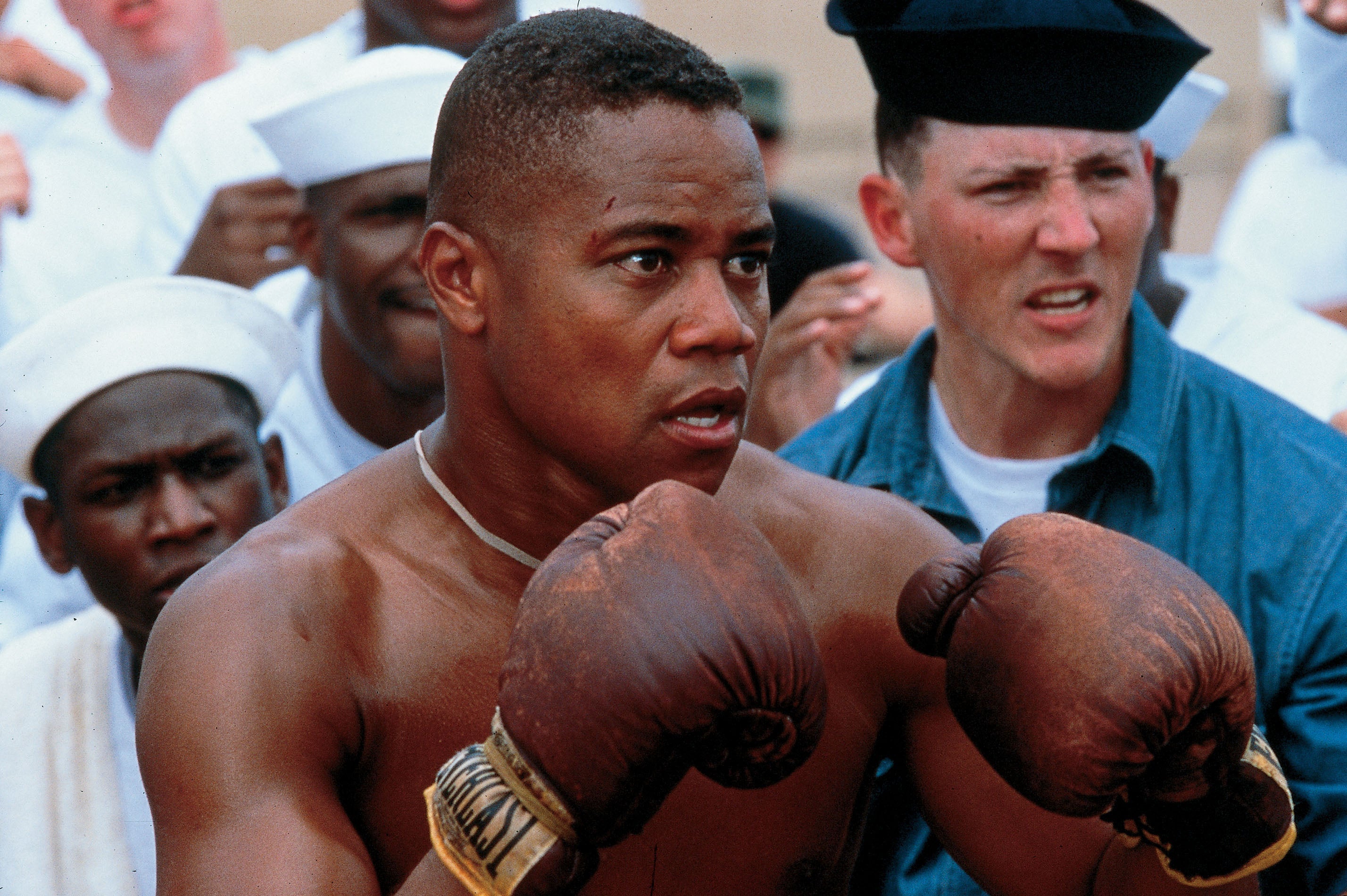

As clunky as the music is the patronising portrayal of the Cuba Gooding Jnr character, the African-American cook Dorie Miller who finally gets to come up on deck and show his courage when the Japanese attack.

However, what the critics who pounded Pearl Harbour failed to acknowledge was Bay’s formal mastery and the breathtaking quality of much of the filmmaking. “He has the best eye for multiple levels of pure visual adrenaline,” Steven Spielberg said of him.

Once the Japanese raid starts in earnest, the director demonstrates his unique ability for shooting and choreographing action. The film shows astonishing visual inventiveness, whether it’s the (admittedly wildly improbable) Top Gun-like sequences of Affleck and Hartnett taking to the skies to fight back against the Japanese planes, the nurses trying to rescue their patients amid the ongoing destruction, the slow-motion strafing of the civilians or the extraordinary shot of a Japanese bomb landing on a US ship from a very great height.

Immense detail went into scenes that last only a second or two. In the aftermath of the attack, for example, Bay shows a minister up to his waist in water as he prays for the victims floating beside him. At another point, we see a fishing net full of corpses.

The director displayed a certain forbearance in waiting until about 80 minutes into the movie to start the pyrotechnics. Once he begins, though, he won’t stop. As the stunts and explosions multiply, their impact diminishes. It feels like a theme park ride that’s lasting too long.

Nonetheless, the film is dealing with a seismic moment in American history, “a date which will live in infamy” as President Roosevelt (Jon Voight) calls it. “We’ve been trained to think that we are invincible. Now, our proudest ships have been destroyed by an enemy we considered inferior. We are on the ropes, gentlemen,” Roosevelt tells his advisers and chiefs of staff of the knock to national morale and self-esteem. The final part of the film deals with the revenge raid on Tokyo led by General Doolittle (Alec Baldwin) in the spring of 1942, but this assertion of American might can’t wipe away the humiliation in Hawaii.

Despite the negative reviews, Pearl Harbour performed moderately well at the box office and then did bumper business on DVD when released at the end of 2001, shortly after 9/11, a similarly scarring moment on the American psyche. “All of a sudden it was cool to be patriotic again,” Bay later commented to GQ about the film’s newfound burst of popularity.

Two decades on, no one is going to pretend that Pearl Harbour is a masterpiece. Its flaws and contradictions are self-evident. However, it is a reminder of a time in Hollywood, now sadly long passed, when big budget movies could still be made without superheroes. In its own erratic, scattergun way, it was teaching younger cinemagoers about an episode in American history that might otherwise have passed them by. Compared to some of Bay’s later movies, it’s a model of subtlety and restraint. The irony is that the biggest bombs weren’t on screen – they were the ones being lobbed in Bay’s direction by critics determined to do to his film exactly what the Japanese did to the American fleet.

‘Pearl Harbour’ is available on Amazon Prime

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments