‘The lunatics have taken over the asylum’: Scarlett Johansson’s row with Disney is a familiar Hollywood story

As the ‘Black Widow’ star’s bitter dispute with Disney over profits rumbles on, Geoffrey Macnab looks back at the long line of actors who have challenged their Hollywood paymasters and asks: does star power ever win?

Scarlett Johansson may not look or behave like a lunatic but she is now regarded as one in certain quarters of Hollywood.

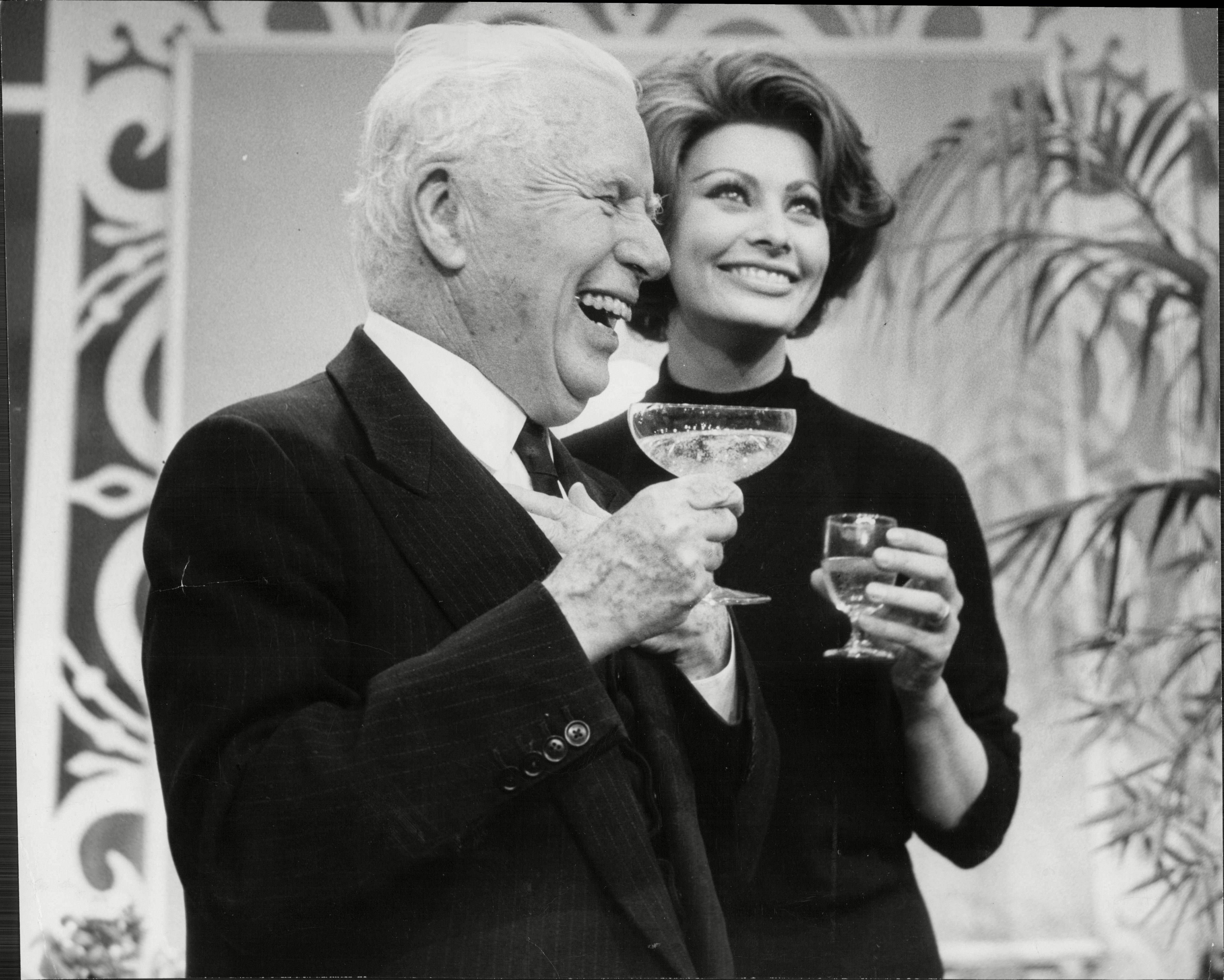

“So the lunatics have taken charge of the asylum,” a senior studio executive commented in 1919 when he discovered that the three leading movie stars of the day – Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks – together with the top director, DW Griffith, had founded their own breakaway company, United Artists. They were determined to hold on to the profits from their films. They were the “talent”, after all, and were deeply suspicious that the Hollywood moguls were trying to railroad them into signing highly restrictive contracts that would curb both their artistic freedoms and their salaries.

Chaplin, Pickford and co issued a high-minded statement in which they vowed to protect the public from “threatening combinations and trusts that would force upon them mediocre productions and machine-made entertainment”.

Flash-forward just over a century and you find a very similar situation. The threatening “combination” in 2021 goes by the name of Disney+, the new streaming service that controls Pixar, Marvel and Star Wars, among many other brands. The rebel with a cause, this time, is Johansson. She may not have launched her own studio but she, too, is in open revolt against the Hollywood bosses.

Disney is pushing hard to boost subscriber numbers on Disney+. Its recent blockbuster, Black Widow, which Johansson executive-produced as well as starred in, was released simultaneously in cinemas and on the streaming platform. The film has been well-received but box office receipts are puny by comparison with the billions other Marvel superhero movies have made, primarily because it hasn’t had the same lengthy exclusive cinema run as its predecessors.

Last week, Johansson issued a lawsuit against the studio, claiming that Disney’s decision to make Black Widow available on VOD at the same time as it hit the big screen “dramatically decreased box office revenue”.

According to The Wall Street Journal, the decision may have cost her more than $50m in lost earnings. The suit also claimed that the Disney top brass benefit financially from the performance of Disney+ and therefore have a vested interested in showcasing the film on the new platform.

The dispute has quickly turned very nasty. Disney is briefing against Johansson. The company dismissed her lawsuit as having “no merit whatsoever”, calling it “sad” and “callous”. They also revealed that she had been paid $20m to star in it. This was a calculated attempt to portray her as pampered, overpaid and out of touch with public feeling during the Covid crisis.

It remains to be seen what long-term damage might be caused to the Avengers franchise and to the Disney family-friendly brand, or whether Johansson will work with the company again. What makes the spat so intriguing is how similar the language being bandied about now is to the rhetoric used over a century ago, when Pickford, Chaplin and co were trying to break away from the studio system.

The same complaints are being made now as in 1919 about “crazy actors getting astronomical salaries”. There is also the same move towards consolidation among the major companies. Using the pandemic as a smokescreen, corporations like Disney and Warner Bros are reinventing their distribution models, increasingly bypassing or sidelining cinemas. In doing so, they are weakening the power of the stars whose remuneration has long been tied to box-office performance.

Johansson isn’t the only leading actor currently in dispute with her paymasters. Action hero Gerard Butler is suing independent movie company Nu Image/Millennium for missing profits from his 2013 thriller, Olympus Has Fallen. Other stars have made their displeasure clear about Warner Bros’ decision to release all their movies in the US this year simultaneously in cinemas and on their streaming service HBO Max.

These disputes highlight the studios’ extreme distrust towards the “talent” with which they work so closely. The history of Hollywood is one of attrition and continual bad feeling between the stars and the executives who hire them. They are mutually dependent but resent each other enormously.

The BFI has just launched an extensive Bette Davis season. One of the films screening is Of Human Bondage – and that title sums up perfectly the acerbic star’s attitude towards her working conditions in Hollywood, which she once likened to slavery. Davis bitterly resented the way Warner Bros forced her to take roles in films she despised. In 1938, she was suspended by the studio after refusing to appear in a project called Comet Over Broadway. Davis felt ill at the time but, as she told the press, she would have soldiered on anyway if the film had been any good. “I did not feel justified in jeopardising my health on behalf of such an atrocious script,” she explained.

This followed on from Davis’s actions two years previously when she had been suspended for refusing to appear as a female logger in God’s Country and the Woman (1936). She had reacted to the punishment by heading off to Britain, hoping to make films there instead, even if in flagrant violation of her Warner Bros contract. The studio took her to court where the prosecutor, using outrageously sexist language, described her as “a naughty young lady”. She lost the case. Two years into a seven-year contract, a chastened Davis returned to Hollywood “to serve five years in the Warner jail”, as she acidly put it.

Like Johansson, Davis felt the studio was riding roughshod over her rights. She wanted more money and more control over her career. Her experiences paved the way for her fellow Warner Bros contract artist Olivia de Havilland, who sued the studio in 1943 and won her case. The so-called “de Havilland law” stopped the studios from arbitrarily extending the contracts of their stars and thereby keeping them in Hollywood’s (admittedly very gilded) version of indentured servitude.

Johansson can be seen as a modern-day successor to Davis and de Havilland – an A-list star with the gumption to stand up to the Hollywood studio chiefs. Many believe she is being treated with the same condescension and contempt that they once were.

“This gendered character attack has no place in a business dispute and contributes to an environment in which women and girls are perceived as less able than men to protect their own interests without facing ad hominem criticism,” activist groups Women In Film, ReFrame and Time’s Up complained of Disney’s statement about Johansson.

If you want to know why Hollywood stars get paid as much as they do, you need to look at the 1950 black and white western, Winchester ‘73, one of the first and best of many collaborations between director Anthony Mann and star James Stewart. The way the film was financed was revolutionary at the time, with Stewart encouraged by his agent Lew Wasserman to waive his normal $200,000 fee (which cash-strapped Universal could barely afford to pay anyway) in return for half the profits. The film’s success instantly turned Stewart into Hollywood’s best-paid actor and gave him a power that few stars before had ever possessed. That was the moment when the lunatics really did begin to take over the asylum.

Robert Downey Jr earned an estimated $75m from Avengers: Endgame thanks to his share of the back-end. This is roughly what Johansson might have expected from Black Widow in more normal times. Instead, after turning up with such haste on Disney+, it has become the most pirated film of the year and has prompted Johansson to launch her landmark legal case against the studio. Is she fighting for money or artistic freedom? As history has shown, in the Hollywood madhouse these two subjects can never really be prised apart.

‘Black Widow’ is on Disney+ and in selected cinemas. The BFI Bette Davis season runs throughout the month

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks