Oasis are reforming and the signs are everywhere that it’s a return to 1997 all over again

With an Oasis reunion confirmed just a few months after a Labour recreated Tony Blair’s landslide victory, Richard Benson, who was editor of ‘The Face’ during the time of ‘Cool Britannia’ , explains why the Nineties was such a vintage era from politics to music and fashion

The day I heard Vanity Fair was coming to do a special report on London’s 1990s pop culture, I was at Liam Gallagher and Patsy Kensit’s home in St John’s Wood, trying to interview them for a cover story in The Face magazine.

I say “trying”, because Liam’s mum Peggy was also there, and she kept chipping in with thoughts about the new houses she and Liam had been looking at. Possibly distracted by their conversation (“I think I like the one with the tennis court better than the one with the big swimming pool, Liam”), I barely noticed when Patsy said Vanity Fair had been in touch about a special London issue. To be honest, it hardly seemed plausible – Vanity Fair was then commanding a huge Hollywood heft, and Liam and Patsy being, well, Liam and Patsy.

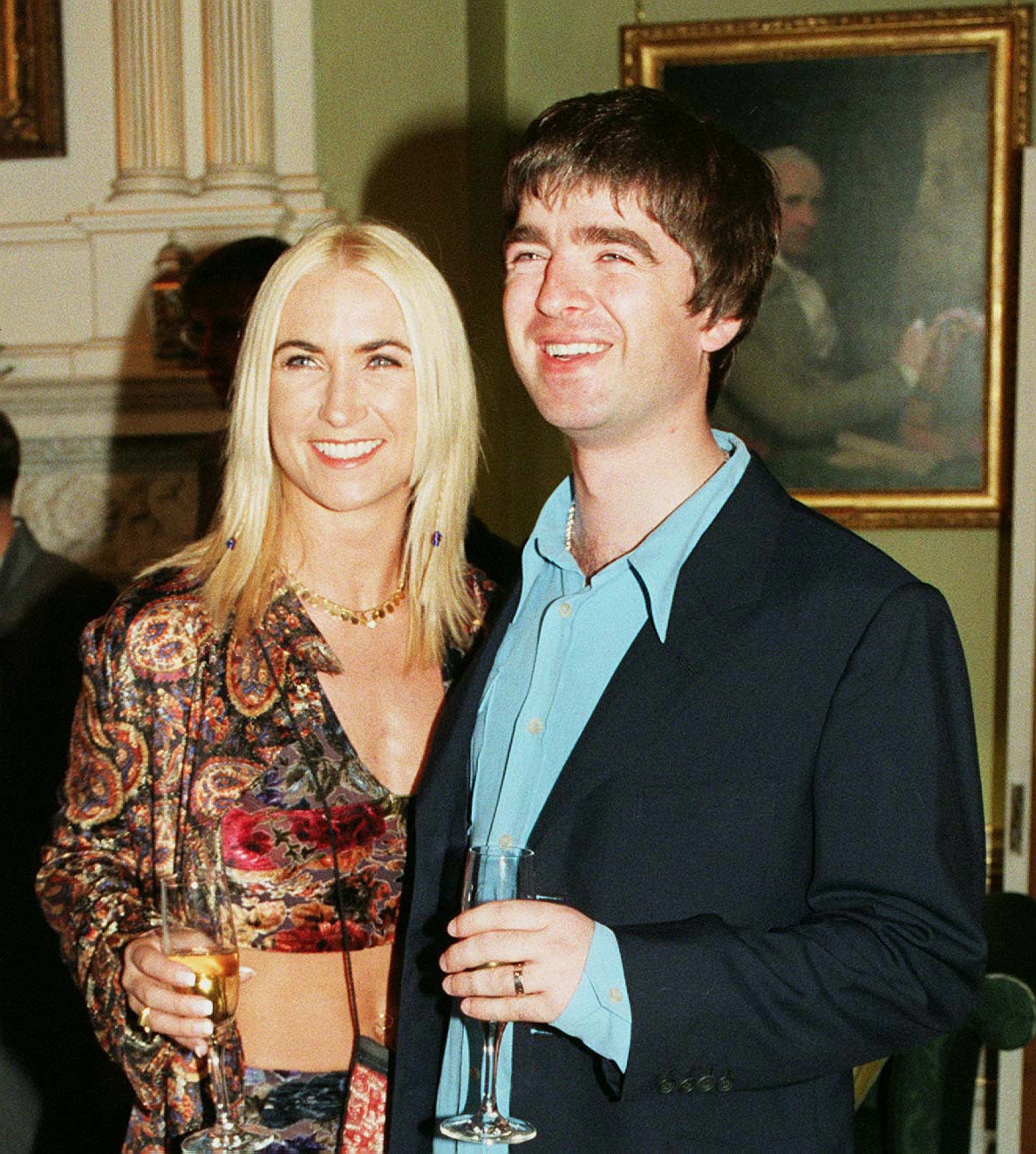

A few months later in February 1997, however, it appeared: a VF cover (featuring the happy couple in bed under the line “LONDON SWINGS AGAIN!”) and 25 pages on how London “got its groove back”. Of course the trendy response was to shrug and say it was all already out of date, mate, but as a Brit it did feel a bit flattering.

People in the UK – not just London – had already felt something interesting was happening in the culture, you could tell that from the way newspapers and TV bulletins had begun covering fashion, house clubs and indie music. But up to that point, it had all been very instinctive and hedonistic. Once you knew serious-minded people overseas were studying it all, you wondered if it might, in the words of Jarvis Cocker, not just be 20,000 people standing in a field, but also about what The Future was meant to feel.

This was all brought to mind again with the 1997-style general election landslide. You can certainly see the parallels between May 97 and now: in both cases Labour trounced a Conservative party dogged by economic incompetence and sleaze and infighting. And in both cases, its representatives’ actual behaviour has made their newly weaponised values of patriotism feel so absurd that the rest of us in the cheap seats are left hooting derision.

But if there’s a difference, between then and now it’s in the mood. Post-pandemic, current-cost of living crisis, people are angrier and more bitter, and that feels intensified by social media, which expresses and fosters hate much better than it does laughter. By 1997, money had started to come back into the economy, and the ubiquitous spite of social media hadn’t poisoned the national mindset; where 2023 has furious memes, the 1990s had a Viz cartoon about a corrupt Tory called Baxter Basics.

The day after the election in 1997, the entire Face office staff gathered around a TV (no smartphones then, and only very techy people could get the telly on their computers) to watch Tony Blair’s famous, choreographed entry to Downing Street. It did feel like living through A Historical Moment, and it seemed vaguely connected to that returning “groove”. In the preceding months there had been a lot in the culture that felt new and exciting, that spoke to a Gen X audience big on irony and pop, and that you knew was going to be significant for the future, good or bad.

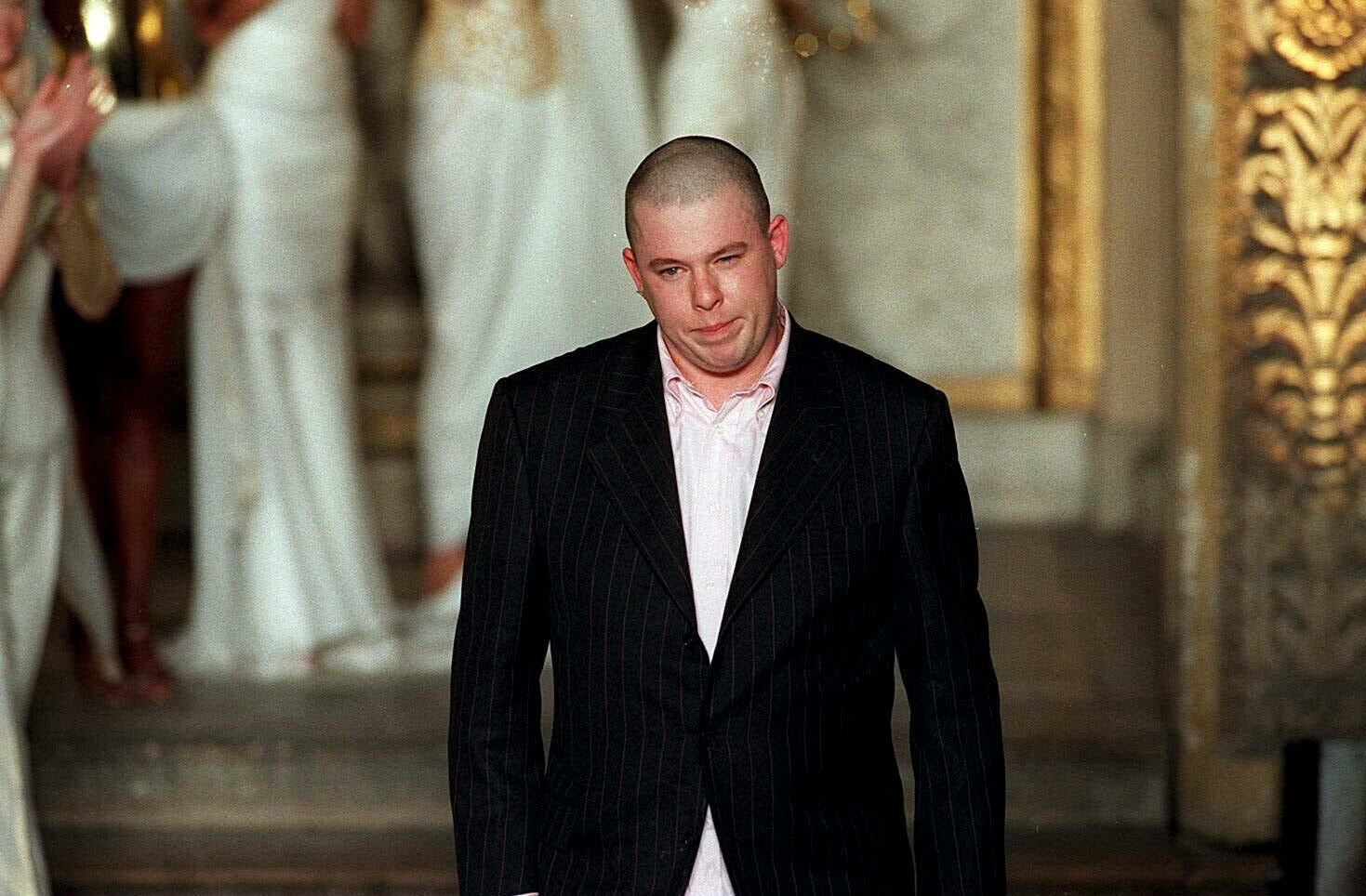

Not just Trainspotting and Tarantino, but the post-modern knowing reboot of the Bond franchise and the first Harry Potter novel; not just Britpop, but Jay-Z, Portishead, drum’n’bass, Daft Punk and, oh alright then, the Spice Girls; not just baggy Nineties fashion but Miuccia Prada, Casely-Hayford, Julien Macdonald and Alexander McQueen.

All these seem so familiar and respected now that it’s hard to imagine how rule-breaking it all felt back then and how much the arts and media establishment of the early 1990s hated it. Don’t forget that the Conservatives seriously tried to get rid of raves by passing a law banning music with “repetitive beats”. Even the liberal boomers in charge of the arts pages then didn’t really understand the irony, the heavy pop-culture referencing and the use of pop as a serious medium that was Gen X’s hallmark.

An example: I once wrote a review of an early Alexander McQueen show, and had the temerity to suggest that it could be seen as a piece of theatre in its own right. A week later, a newspaper carried a short piece laughing at the idea that “fashion” could be linked with “theatre”. Now that feels just par for the course.

No one thought New Labour were going to change the world: in fact, a lot of people had rather given up on the idea of changing the whole world, and retreated into the idea of cocooning in their own subcultures. But you did think that in that famous “big tent” of theirs, your voice and your culture might get noticed rather than mocked or attacked. Noel Gallagher and Stella McCartney were invited to Tony’s No 10 “opening” party and it did feel like a new clean brush was sweeping out the “old” ways. That’s why it’s important to remember that the attractive, early version of New Labour talked more about inclusivity than “centrism”.

And there was a sense that the party had been listening.

Working on The Face in the 1990s put you in the fortunate position of talking to the smarter people in pop about serious ideas, and in those conversations, it became apparent in the early 1990s that articulate musicians, DJs and artists, (Brett Anderson, Louise Wener, Damon Albarn, Trevor Nelson, Andrew Weatherall, Jeremy Deller) were becoming interested in reinventing the idea of Britishness.

The basic idea was that if you celebrated all sections of society, then you could create a kind of positive, open nationalism that wouldn’t be aggressive but would foster self-respect and allow everyone to express themselves.

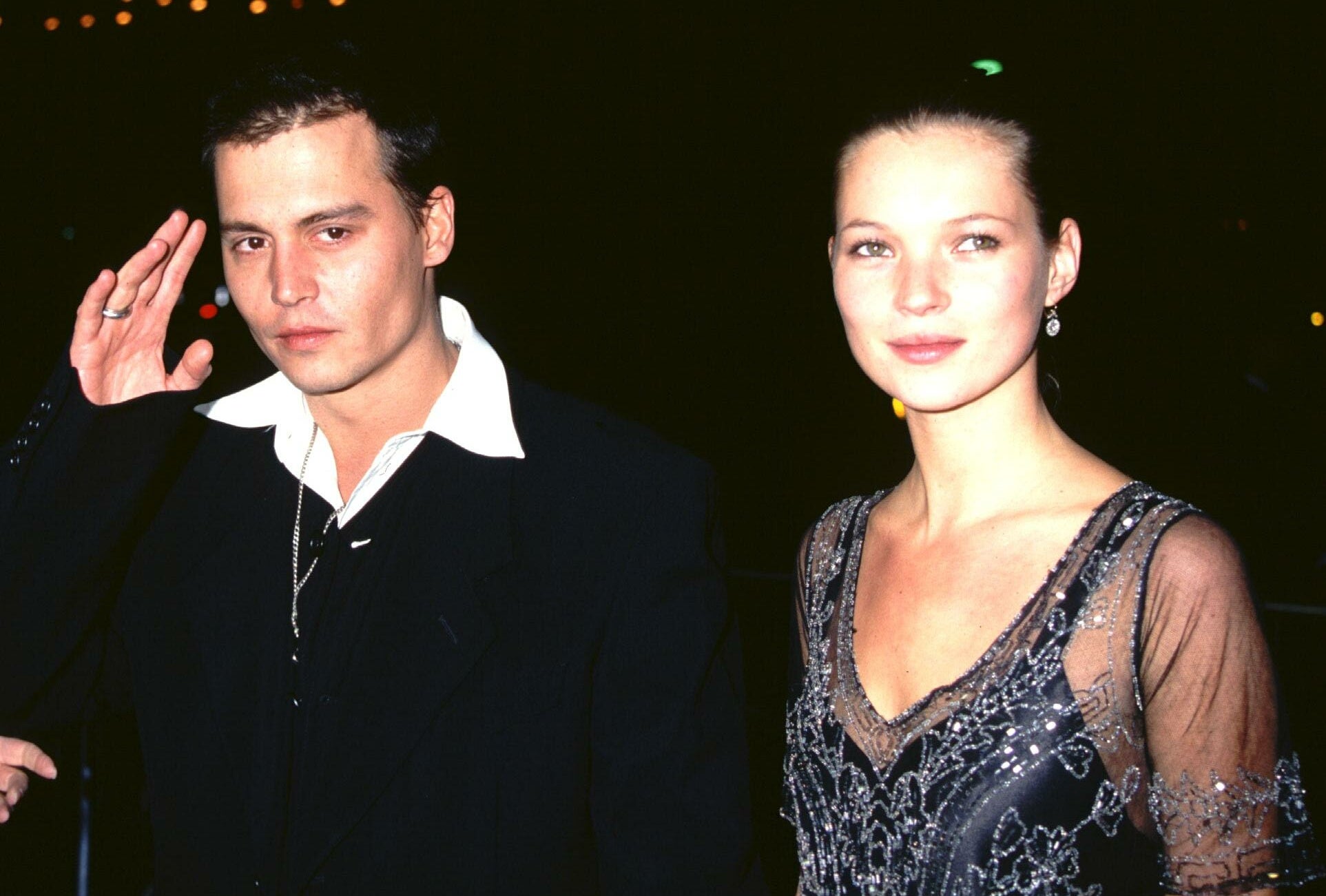

I appreciate that this might sound like it’s reading an awful lot into Parklife or a Kate Moss photoshoot, but it was absolutely real and explicitly discussed at the time. The photographer Corinne Day, whose photographs of Moss in The Face launched the model’s career, was adamant that that was the point of her fashion shoots in which Kate looked like the ordinary suburban teenager she was. Day’s insistence that the images “look British, and look modern” became like a sort of catchphrase in the office.

This idea was heard in Albarn’s railing against the hegemony of American rock at the 1992 Brits and would reach its fullest expression 15 years later in Danny Boyle’s opening ceremony for the 2012 Olympics. This wasn’t simply concurrent with New Labour’s rethinking of patriotism, it was part of a continuum; the think tank Demos produced an intellectual version of it in their 1997 report Britain (TM), and had consulted Blair for years leading up to the election campaign. The events of 1997 can be seen as the idea rendered in flesh, music and really cool old-school trainers.

If you were really looking to understand what happened in 1997, though, you also need to understand that generation of twenty and early thirtysomethings that voted New Labour into power. Because in many ways, the roots of that victory were made not in the 1990s, but many years before.

For many of us who didn’t grow up wealthy and came from outside the South East, our entire lives before the mid-90s had been coloured by the sense of economic depression in the North. I came to London in 1991 from Hull and met friends who were from Manchester, Leeds and Wigan. At home parents spoke of the dark days of the 1970s, and then there had been the recession of the early 1980s. If you were born in an industrial area as I was, these continued well into the mid-80s, just in time to catch the 1990 slump.

We wanted the people who still worked in those old industries to be respected, but we knew they would never reattain their former glories, and so in the early 1990s a lot of us headed down south looking for work with a sort of let’s-see-what-happens, fortune-hunting kind of approach; one thing now that is really different is how the trendy culture of the day was dictated by working-class kids who had just come to London to have a laugh and have a go.

No wonder Generation X was known for being self-effacing, and why it didn’t take itself as seriously as the boomers and millennials on either side. When you’d spent your childhood thinking the country was in decline and about to fall apart, it can be hard to treat life with much earnestness. It’s not really any surprise that the 1990s saw such a huge boom in comedy, much of it (Reeves & Mortimer, Harry Hill, League of Gentlemen) surreal.

The humour and self-mockery we developed in order to cope might have been our strongest asset. In retrospect, looking back to a time when you didn’t have to worry someone might take a photo of you in an embarrassing moment, it certainly seems like enjoying oneself in the moment was just a bit more straightforward.

The 1990s gets a bad rap these days for its loud lad culture, for which Oasis were the poster-boys, but I think this is a misjudgement. To me it seems like a more thoughtful, compassionate corrective to the flash 1980s, and one that somehow managed to lay much of the foundations for 2000s culture while being reluctant to take much credit for itself.

I do wonder if the generation that has just come of age since the credit crunch might have had similar-ish experiences, and feel shut out today as people did then. If so, and if Keir Starmer wants to maximise his 1997 election rerun, he should get a bigger tent, and invite them into it. Because that is when the real magic happens.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks