Graphic sex, defecating nuns, and the Virgin Mary: Why film-makers are still obsessed with religion

The Dutch director of ‘Showgirls’ and ‘Benedetta’ – a movie about a 17th-century lesbian nun – is still planning to make a film about Jesus. Paul Verhoeven talks to Geoffrey Macnab about trying to follow in a long line of directors who’ve portrayed Christ on screen

Jesus appears briefly in Dutch director Paul Verhoeven’s new feature Benedetta – an overwhelming succès de scandale in Cannes last week. The film is wilfully and wildly provocative. If you enjoy stories that include defecating nuns, Virgin Mary topped sex toys and plenty of sapphic writhing, wriggling and tickling beneath the wimples, rejoice: this one’s for you.

It stars Virginie Efira as Benedetta Carlini, a lesbian 17th-century nun who is having visions of Jesus on the cross that fuel her wildest erotic fantasies. In Benedetta’s fervent imagination, the saviour of the world is her demon lover. She pictures him as a rugged, bloodied, alpha-male type whose crown of thorns and swordsmanship skills only add to his potency and attractiveness.

At first, Jesus warns Benedetta to stay away from Bartolomea (Daphne Patakia), the beautiful young woman who has found refuge from her abusive father in the convent. But then he changes his mind and tells her to take her clothes off after Bartolomea asks to see her naked.

It all seems very blasphemous and absurd. However, Verhoeven, speaking to me at last week’s Cannes premiere, claims that the film’s portrayal of Benedetta is based directly on contemporary records. He took the information from Judith C Brown’s academic book, Immodest Acts. “The book is about a lesbian… a nun who becomes a lesbian,” he says. “That is what happens. It is the real story.” He is not making the stuff up. This is how Benedetta really did envisage Jesus.

“What I try to do in Benedetta is show the Jesus that she saw,” he quickly clarifies. “That is her Jesus. That is not my Jesus.”

Verhoeven has been obsessed with Jesus for a very long time. He has written a scholarly book about him, Jesus of Nazareth, which was praised as “shrewd and learned” by The New Yorker, and has spent at least a decade trying to make a movie on the subject. This promises to be far more serious in tone than Benedetta.

If he succeeds, he will be following in a very long line of directors who’ve portrayed Christ on screen. The list includes Cecil B DeMille, George Stevens, Nicholas Ray, Martin Scorsese, Mel Gibson and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Joaquin Phoenix, Jeffrey Hunter, Max Von Sydow, Willem Dafoe, Jim Caviezel and Robert Powell are among those to have played Jesus.

Why is the director of Basic Instinct and Showgirls so tempted by the idea of telling Christ’s story on screen? Verhoeven is already in his eighties. This would surely be his final flourish as a filmmaker.

Christ is regarded by Verhoeven as a freedom fighter and a rebel. “I really feel that when the Romans executed him – not the Jewish people; the Romans of course – from the Roman point of view, Jesus at that time was an insurrectionist, and was basically against the emperor.”

Executing him was, Verhoeven believes, perfectly legitimate. After all, this was a leader who, according to Luke (22:36), told his followers to take up weapons: "Let the one who has no sword sell his cloak and buy one."

“As he was not a Roman, [they decided] he should be crucified. It is never mentioned too much but I believe that the Romans, from their own point of view, were legal when they did it,” says Verhoeven.

The Verhoeven Jesus is going to be “Che Guevara like”. “If Jesus was talking for 30 minutes about the Kingdom of God and the parables, that would still be very boring. I want to be sure that the narrative is interesting…I wouldn’t do it if I feel that it is mediocre or that it has been done by Pasolini or others, if it is not new enough.”

Don’t expect miracles or high-minded theology. Verhoeven’s Jesus sounds as if he will be as feisty as Mel Gibson’s Braveheart. The film, if it ever comes to fruition, is bound to be full of the director’s trademark visual flourishes, bloodshed and violence.

The more serious intention, though, is to work out why people continue to pay attention to Jesus. Whether or not they identify as Christians, they still live by his humanist precepts. “What I really want to show is what did Jesus say or stand for that is still interesting for us now. Not that Jesus is God or part of the Trinity. That has no educational value in my opinion at all. But the parables of Jesus have value.”

The director and screenwriter David Birke, who collaborated with him on Benedetta and its predecessor Elle, are working on a new treatment. “After the festival,” says Verhoeven, “we will be sitting together in the Hague [Verhoeven’s hometown] to work first on an outline and then decide ‘can we do the movie or not? Is it honest enough?’”

Obvious perils always lie in the path of filmmakers depicting Christ. If they’re too flippant, they will be attacked by Christian groups. This was the fate of the Monty Python team after they made Life of Brian starring Graham Chapman as a very down-to-earth messiah.

If they’re too violent, they will be labelled sadists, as happened to Gibson when he made his blood-saturated Passion of the Christ. If they show Jesus in too mild and caring a light, they might be called wimps or communists.

This isn’t an easy role to cast or to play either. “Playing Jesus was in a way an impossible task,” Swedish actor Max Von Sydow told me in an interview late in his life as he looked back on his role in George Stevens’s The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965). This was his first acting job in a non-Swedish film. It involved several surrealistic moments, such as being dunked in the water by a very hairy looking Charlton Heston, who was playing John the Baptist, or having John Wayne attend his crucifixion.

“Truly this man was the son of God,” said Wayne, as the Roman centurion, who drawled out his lines as if he was in a saloon bar in Dodge City. The extras were all true believers who couldn’t understand why Von Sydow didn’t share their zealous faith. “They expected me to be dedicated on every level, which of course I wasn’t. I was professionally dedicated, but that was all.”

The film did decent business and picked up five Oscar nominations but cost a fortune to make and lasted for a small eternity. It was described by critics as “a big, windy bore”. It didn’t help either that everyone already knew the ending. Although once a fixture on UK TV, it is rarely shown today.

You can’t imagine Verhoeven making a film as pious and long-winded as The Greatest Story Ever Told. However, if he is perceived as being disrespectful toward Jesus, he is likely to face the same wrath as Scorsese on The Last Temptation of Christ. Fundamentalist religious groups were infuriated by Scorsese’s film long before a foot of it had actually been shot. They had got hold of an early draft of the screenplay that had Jesus speaking to Mary Magdalene in a very Verhoeven-like way, saying: “God sleeps between your legs.”

This line was eventually taken out but the very fact it had once been there was enough to create a storm. Scorsese was forced to defend himself, issuing a statement saying the film had been made with “deep religious feeling” and was “an affirmation of faith, not a denial”. Even so, the project remained shrouded in controversy.

Scorsese, like Verhoeven, has often paid tribute to Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St Matthew, still regarded by many as the greatest – or the least embarrassing – attempt to tell the story of the man from Nazareth on screen. Pasolini was a gay Marxist atheist, not a Christian. Nonetheless, he respectfully dedicated his film to “the dear, familiar memory of Pope John XXIII”.

“I am an unbeliever who has a nostalgia for belief,” said Pasolini about why he wanted to make it.

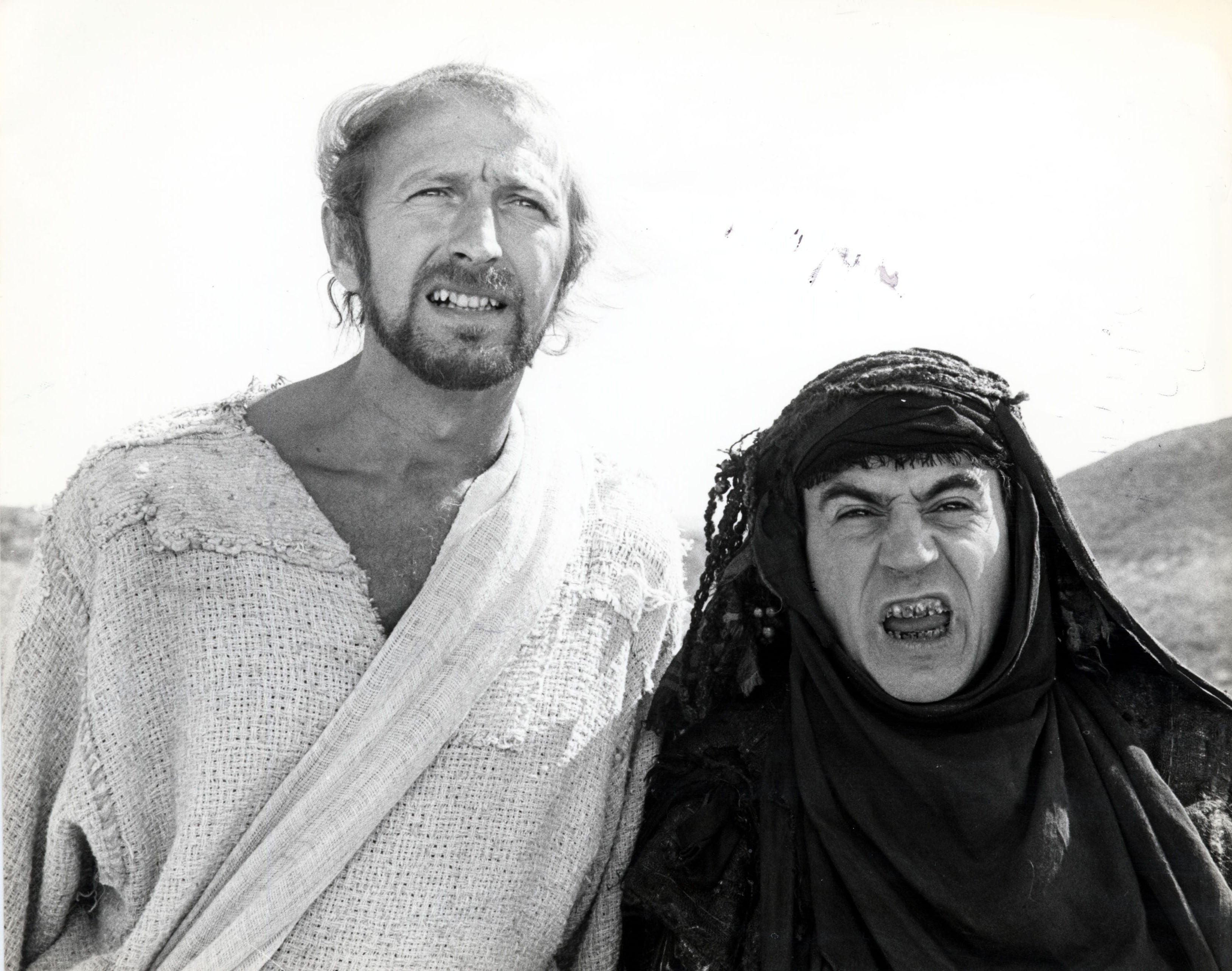

The brilliance of Pasolini’s film lay in its freewheeling lyricism. It was shot without a script and filmed in black and white, in a naturalistic fashion a long way removed from the gaudy excesses of Technicolor, widescreen Hollywood biblical epics. Most of the actors were non-professionals. The words that Jesus utters almost all come from the scriptures.

No one has been painted, drawn or sculpted as often as Jesus. Filmmakers have been strangely reticent in depicting him but he has been the main subject for western artists for hundreds and hundreds of years. Pasolini realised that he had a huge archive of images to draw on. He frames scenes as if they are old Renaissance paintings and fills the film with huge, expressive close-ups of Jesus, Mary and the disciples.

The most expensive artwork in history, Salvator Mundi, which Leonardo Da Vinci may have painted in part or entirely, and which the Saudi Arabians bought for just over $450m in 2017, is of a Jesus who looks very like the character as played by Enrique Irazoqui in Pasolini’s film.

The Gospel According to St Matthew is deceptive. In its early scenes, it may seem like a European art house version of a school nativity play but it grows ever more subversive. Its protagonist is far less meek and mild than he first appears. As played by Irazoqui, he is a single-minded, uncompromising figure who demands complete loyalty from his followers. His parables have a very sharp edge. He doesn’t disguise his scorn for the money lenders, the elders, the scribes and the chief priests.

Verhoeven’s Jesus is likely to be similar to the revolutionary leader shown by Pasolini. You can see why the ageing Dutch enfant terrible is so drawn to the subject. It’s a last great challenge to round off his career, a chance to trump everyone from DeMille to Scorsese and to make a film that appeals both to a general audience and to die-hard Christians. The odds seem stacked against him. It will be a small miracle if the film even gets made – but Verhoeven has pulled those off before.

‘Benedetta’ was a world premiere at The Cannes Film Festival. ‘The Gospel According to St Matthew’ is available on Amazon Prime

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks