JFK at 30: Is Oliver Stone a crackpot or a prophet?

With Stone presenting his new Kennedy documentary in Cannes next week, Geoffrey Macnab looks back on the director’s 1991 film about the assassination and how his conspiracy theories are regarded today

Artists have their obsessions. Paul Cézanne painted the same mountain again and again. Edgar Degas had his fetish for young female ballet dancers. And Oliver Stone can’t help making films about the assassination of President John F Kennedy on 22 November 1963 in Dallas, Texas.

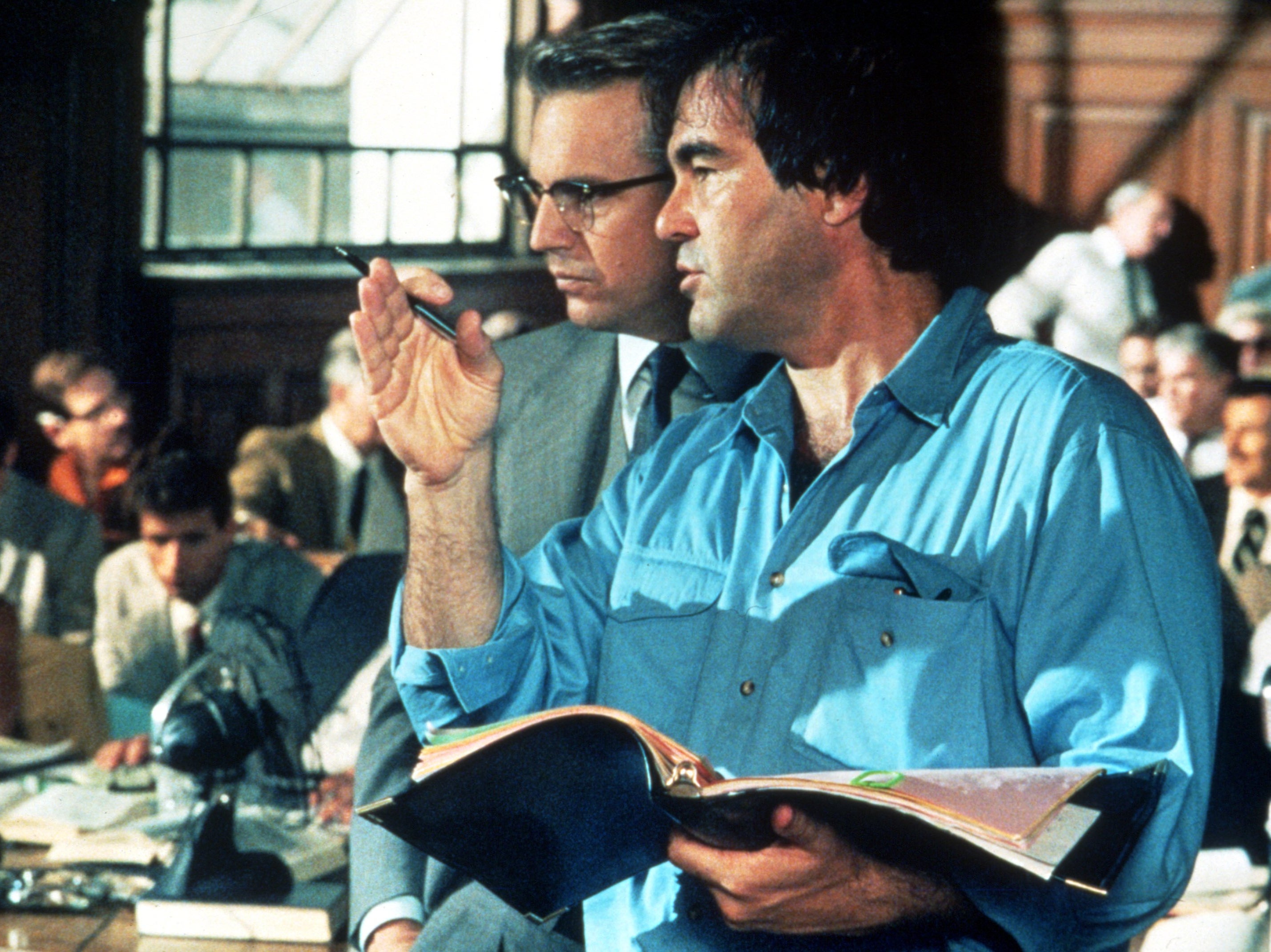

It’s 30 years now since Stone’s epic JFK, in which crusading New Orleans district attorney Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) rejects the Warren Commission’s conclusion that a lone gunman was responsible for Kennedy’s assassination. Instead, Garrison goes after a shady businessman, Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones), who he believes was involved in a complex murder conspiracy.

Stone was both praised and ridiculed when JFK came out. The film was called “a basket case for conspiracy”. Revered newscaster Walter Cronkite described it as “a mishmash of fabrications and paranoid fantasies”. The prevailing view was that this was a tour de force in cinematic terms – it won Oscars for cinematography and editing – but deeply unreliable as history.

Now, Stone has revisited exactly the same subject matter in JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass, but this time as documentary rather than drama. The new film receives its premiere at the Cannes Festival next week.

“Stone presents compelling evidence that, in the Kennedy case, ‘conspiracy theory’ is now ‘conspiracy fact’,” trumpets the advance publicity. The maverick American director clearly expects his latest foray into conspiracy land to vindicate him. Ideas about Kennedy’s death that seemed outlandish in 1991 have, Stone believes, been moving closer and closer to the mainstream. However, the very title, Through the Looking Glass, suggests that when it comes to Kennedy’s death, scholars are still stuck in some Lewis Carroll-like world where nothing ever quite adds up.

Stone’s general thesis about the Kennedy assassination is already clear enough. He ridicules the idea of the “magic bullet” that Lee Harvey Oswald fired at the Kennedy motorcade, which then went on its own zigzagging mystery tour through different parts of Kennedy’s anatomy and also somehow hit Texan governor John Connally, sitting in the front seat. The director is equally scornful about the notion that Oswald, firing from a window high up in a book depository in Dallas with his view obscured by trees, could get off three shots in under six seconds and wreak such devastation.

In the original JFK drama, the American director picks up on the many oddities and inconsistencies in the Warren Commission report. Would Oswald really have discharged the shots and then strolled downstairs, stopping for a Coke before he exited the building through the front door?

Nor does Stone leave us in much doubt who he thinks was responsible for Kennedy’s killing. He argues that this was a coup d’etat orchestrated by Allen Dulles and his cronies at the CIA in the wake of the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961. Their motive was clear. Kennedy hadn’t supported them when they made such a hash of toppling Castro in Cuba. The president was threatening to take US forces out of Vietnam and to normalise relations with the Soviet Union. That would have threatened the multi-billion-dollar military-industrial complex that was enriching so many American businessmen and politicians. There were both financial and ideological reasons for having Kennedy killed.

The seething hatred felt for the president by many right-wing Americans is shown in vivid fashion in an early scene of JFK, featuring Guy Banister (Ed Asner), a former FBI officer now working as a very dodgy private investigator in New Orleans. The actor is known for his gruff yet amiable character Lou Grant in the TV show of the same name, but in JFK, his face is contorted with loathing and revulsion at the very mention of Kennedy’s name. “They’re bawling like they knew the man. It makes me want to puke,” he hisses at the grief shown by his fellow Americans after the assassination. He then pistol-whips his friend Jack Martin (Jack Lemmon) in a scene that still seems shocking – you don’t expect an old man to unleash such violence.

Asner’s brilliant, repellent cameo goes a long way to explaining why JFK remains Stone’s finest movie. It distils a huge amount of information into its three-hour running time while telling its convoluted story with huge verve. The director recruited the best actors at his disposal. There is a small army of them, most at the very top of their form.

Gary Oldman plays Oswald as a chameleon-like figure, defiant but strangely naive. “I am just a patsy,” he forlornly yells at the media after his arrest. Stone portrays him as a Josef K-like figure who can’t escape his fate.

Kevin Bacon is louche and outrageous as Willie O’Keefe, the rent boy whom Garrison interviews in a prison in the deep south and who offers tantalising clues about Clay’s involvement in the Kennedy murder plot. He seems charming initially but then, like Ed Asner’s character, he reveals a psychotic hatred of “commies” (including JFK) that disarms even the normally unruffled Garrison.

From Sissy Spacek as Garrison’s long-suffering wife to Walter Matthau as a grizzled old senator and John Candy as Garrison’s venal old law-school friend, the film is packed with stars playing often very small character roles. Stone also provides a platform for Joe Pesci to give his most flamboyant performance outside of Goodfellas as a foul-mouthed and very camp conspirator who becomes Garrison’s most important source.

Even random passersby who have only moments of screen time are played by well-known actors. Vincent D’Onofrio, for example, pops up as a witness to the assassination who is very briefly interviewed.

Stone combines archive and documentary elements (including the Zapruder home-movie footage of the killing) with the drama. He jumps back and forth in time and edits in rapid-fire fashion, as if scared that viewers will lose interest otherwise. The director is like a grandstanding lawyer, using every trick at his disposal to sway a sceptical jury. For all the film’s formal brilliance, it sometimes seems that he is trying too hard. It’s as if he already knows that audiences regard him as a demented conspiracy theorist and he is doing everything in his power to change their minds, charming, cajoling and even trying to bully them into submission.

You can’t escape, either, the strange feeling of anticlimax with which JFK ends. Garrison gives a rousing, brilliantly argued courtroom speech that lasts for a small eternity… and then Clay wriggles free anyway. Just as Garrison failed to achieve his aims, so at first did Stone. However, the director is like the ancient mariner in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem, the grey-bearded loon who just won’t shut up.

One of the last lines uttered in the film by Garrison is: “If it takes me 30 years to nail every one of the assassins... then I will continue for 30 years!” Now 30 years have passed since JFK was released. Garrison, who served as an adviser to the film and also had a cameo, died not long after it came out, in 1992. With his passing, Stone has picked up the mantle and is bringing JFK’s assassination to public attention once again with his new documentary.

“There is a memory hole about Kennedy. And I think, before I quit the scene, I would like to reveal what I know about the case,” the director told The Hollywood Reporter this week.

True to form, the new film is already shrouded in controversy. In 2017, President Trump took a last-minute decision not to release, as he had promised, certain key documents relating to the assassination. There is therefore a sense that Stone still hasn’t been able to tell the full story.

Many will continue to regard the director as an obsessive crackpot. Nonetheless, there are plenty of politicians, medical and ballistics experts, scientists, historians and witnesses who share his views about what happened on that November day in Dallas.

As a young man, Stone fought in Vietnam in a war that JFK was desperate to avoid. The assassination therefore directly affected his life – perhaps the conflict would have ended sooner had Kennedy lived. Stone continues to argue that this was the pivotal incident in recent American history, too, the moment that the dark forces triumphed and the great divide now so apparent in US culture and politics first began to appear. That part of his theory, at least, is hard to disagree with.

‘JFK’ is available on Amazon Prime. ‘JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass’ premieres on 12 July at Cannes Film Festival

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks