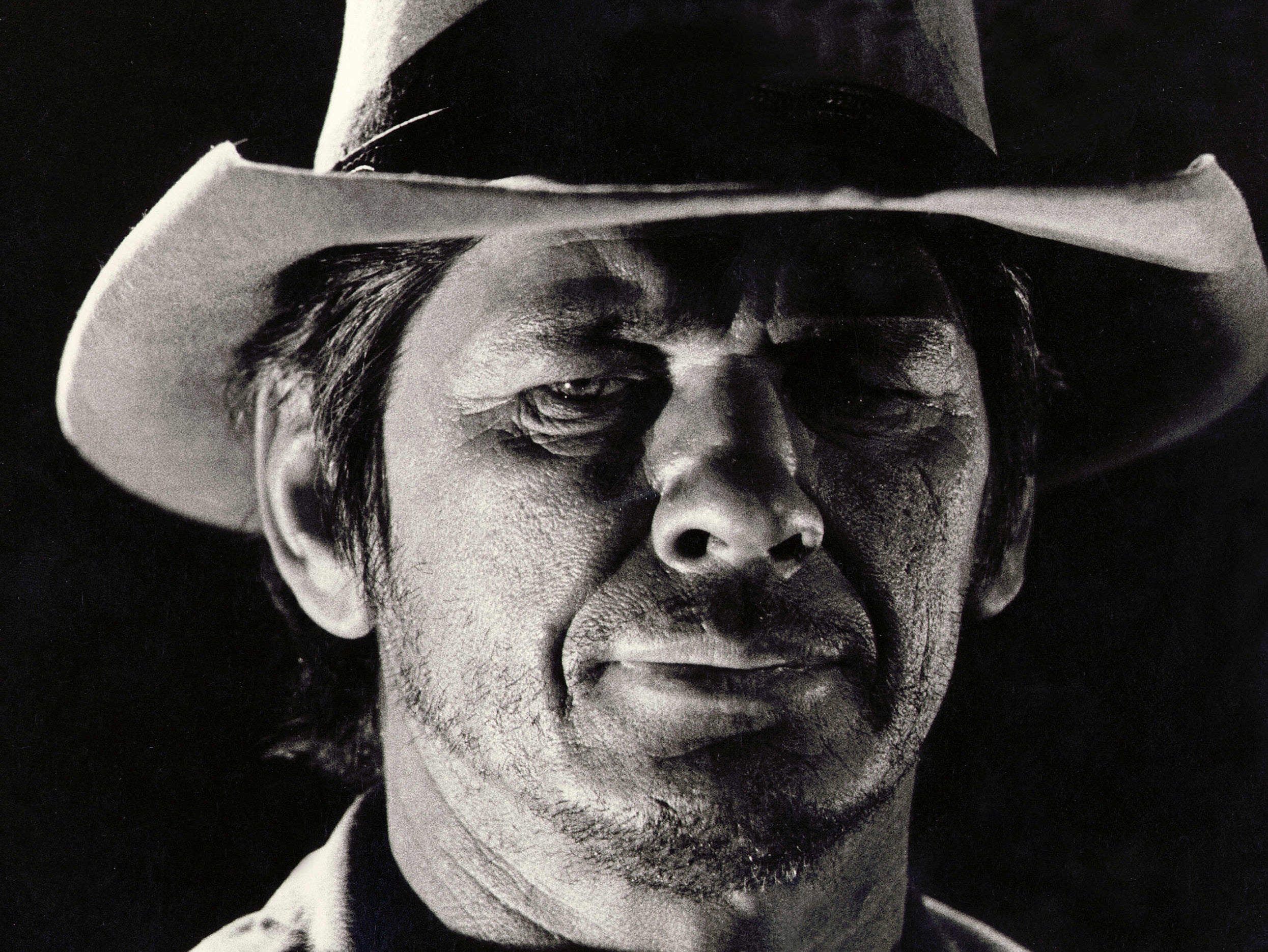

Charles Bronson at 100: Why action stars like Liam Neeson owe him a debt

The actor is best remembered for his role as the taciturn, ultra-macho vigilante in the critically derided Death Wish movies. On the centenary of Bronson’s birth, Geoffrey Macnab looks at how he actually set the template for the modern action hero

Towards the end of Death Wish 3, Charles Bronson’s vigilante hero is threatened with a gun by Gavan O’Herlihy’s gang leader. The thug has seemingly come back from the dead after already being shot once – in fact, he is wearing a bulletproof vest. This time, our hero takes aim at him from point blank range with a rocket launcher, completely obliterating him. It’s an absurd, nonsensical finale to an absurd, nonsensical film in which the death count is through the roof. Bronson’s expression doesn’t change. He looks utterly unperturbed, even slightly disinterested, as if he is performing an everyday domestic chore before he picks up the $1.5m cheque that Menahem Golan and Yoran Globus, the maverick Israeli producers of Michael Winner’s 1985 film, have promised him for services rendered.

This year marks the centenary of Bronson’s birth. He was the most enigmatic action star of his era, one who appeared in his share of terrible films without it ever seeming to compromise his reputation. His brand of macho minimalism has proved hugely influential. Actors like Bruce Willis, Liam Neeson and Jason Statham have played similarly unexpressive heroes in more recent action movies without ever quite matching his eerie calmness.

Bronson, who died in 2003, doesn’t openly show grief or anger on screen but many of the characters he plays have suffered extreme trauma in their past. Generally, they’re out for revenge. His face is always impassive but, in his better performances, he’ll convey his hurt and yearning through an expressive look in his eyes or (as in Once Upon a Time in the West) by playing a few bars on a harmonica. He is always very gently spoken. That serves both to ingratiate him with audiences – he seems so polite – and to make him all the more intimidating. We know that he could explode into violence any time soon.

In his lesser films, notably those made with Winner, his behaviour frequently seems bizarre. His reserve comes across as a lack of basic human empathy. In one of the more ridiculous scenes in Death Wish 3, the woman (Deborah Raffin) with whom he has just started an affair stays in the car when he goes to collect his mail. Street thugs assault her and cause a crash that kills her. Emerging from the post office, Bronson reacts in typical Bronson fashion, by showing a look of mild annoyance as if he has just received a parking ticket.

Physical pain didn’t faze Bronson’s screen character either. When one of the hoodlums sticks a knife in his back in Death Wish 3, he pulls the blade out and looks at it with curiosity as if he can’t quite believe it was meant for him.

“He [Bronson] is destiny… a sort of granite block, impenetrable but marked by life,” Italian director Sergio Leone is quoted as saying in Christopher Frayling’s biography of the filmmaker. “I met many people in the States – businessmen, heads of corporations – frankly, people who were even harder than the Bronson character. And they have exactly the same smile as Charles Bronson; menacing, unsettling.”

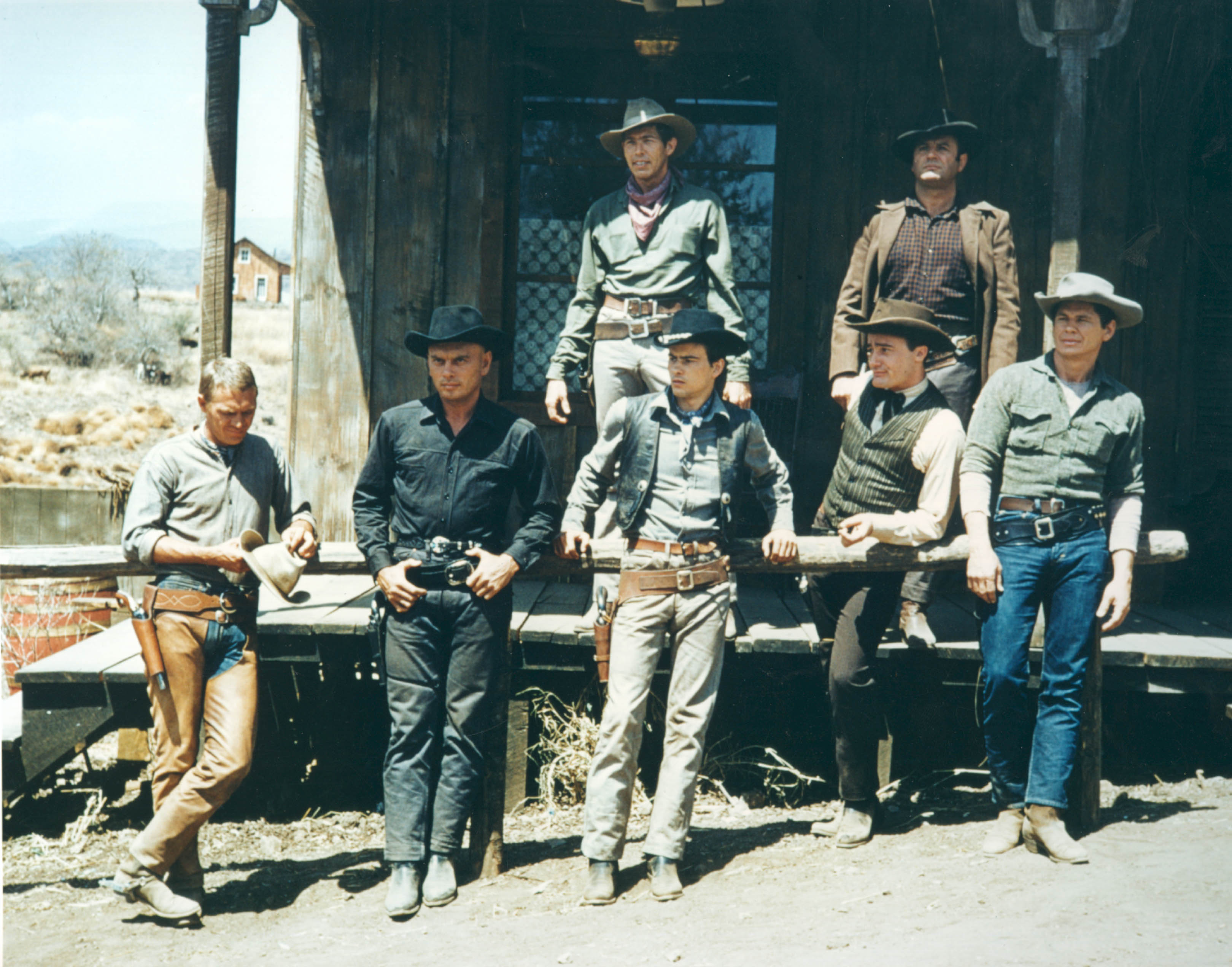

When Bronson landed arguably his greatest role in Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1969), the Paramount bosses were baffled by the casting. They knew him as a supporting actor, one of The Magnificent Seven or The Dirty Dozen who could look mean and charismatic as part of a bigger group but not the type to hang a big budget movie on. Leone, though, saw the rough-hewn American actor as the perfect choice for the harmonica-playing gunman. Bronson was so inscrutable and gave so little away that he fascinated audiences. He was every bit as taciturn as Clint Eastwood’s “man with no name” in Leone’s Dollars trilogy and it was apparent he was hiding something behind those soulful, mysterious eyes of his. He didn’t need to say much. Thanks to Leone’s widescreen close-ups, his face did all the work.

Like Humphrey Bogart, Bronson was well into middle age before he became a star. He’d occasionally led B-movies like Roger Corman’s Machine Gun Kelly (1958) but had been confined to supporting parts in bigger films.

Bronson wasn’t a tall man. On and off screen, he wasn’t extrovert at all. Nonetheless, he was prey to a certain narcissism. He worked out relentlessly, going to extreme lengths to keep himself in the best possible trim. According to director Winner, he had plastic surgery on several occasions. “That wonderfully lined face becomes increasingly bland,” Winner noted of how the star’s features smoothed over after the first Death Wish movie in 1974.

In Walter Hill’s Hard Times (1975), which some see as his definitive role, he was cast a bare-knuckle, street fighting boxer, adrift in 1930s America. He was playing an intensely physical part opposite actors many years younger than him but few of the critics seemed to realise he was already in his fifties.

Part of Bronson’s appeal lay in how different he was to the other male stars of the period, the clean-cut Robert Redford, Paul Newman and Steve McQueen types. Born Charles Buchinsky, he was the child of Lithuanian parents and grew up in poverty in a Pennsylvania industrial town. “Bronson’s eyes are a cat’s eyes, watchful and guarded,” critic Roger Ebert noted in a 1974 profile that called Bronson “the world’s most popular movie star”.

Bronson had achieved that status in a very roundabout fashion, escaping his coal mining background when he was drafted into the army and then, like many others, using the GI Bill to attend art school and study acting. He was feted in Europe and Asia long before US audiences embraced him.

Even as his career took off, Bronson remained an outsider, hostile towards the press and never the type to take part in Hollywood marketing stunts to boost his popularity. “I am only a product like a cake of soap, to be sold as well as possible,” he told Ebert when he very reluctantly spoke to him.

In his early career, Bronson was sometimes cast as Native Americans. He was no Ivy League WASP. You weren’t going to find him in The Great Gatsby or The Sting. There was therefore an irony in his later emergence as the vigilante hero of the Death Wish films. In these films, each more ludicrous than the last, he was the avenging angel, blasting away at young street punks on behalf of a white, middle-class suburban America to which he himself had never belonged.

Bronson was an intimidating figure. Chat show hosts were palpably nervous in his presence. ”I’m not violent. I used to be but not now,” he told a visibly agitated Dick Cavett in one TV interview. Dressed in a black shirt, Bronson was smoking at the time, speaking in such a soft voice that his words took on an extra menace. The handlebar moustache made him look even more like a stranger in a saloon whom all the locals are terrified of offending.

“[Bronson] was different from any man I’d ever known, almost broodingly quiet and intense, with an explosive air of violence about him,” Jill Ireland, who left her husband David McCallum for Bronson, later wrote about him. She and Bronson went on to appear in 15 films together, almost all of them thrillers or westerns. When he did veer away from type, for example when he played a middle-aged pornographic novelist having an affair with a teenage schoolgirl (Susan George) in Richard Donner’s Lola (1969), audiences were understandably baffled.

For all his machismo, Bronson hinted at more refined feelings in some of his films and he was far more passionate about his painting than his acting. Even in movies like Death Wish 3, he would take a break from killing gang members to make small talk with the elderly neighbours over dinner.

Bronson’s influence continues to be felt today. The UK’s most notorious long-term prisoner borrowed his name in 1987 – and was later subject of a biopic starring Tom Hardy. The gritty action movies of recent years – films like Bob Odenkirk vehicle Nobody, The Equalizer or Liam Neeson’s A Walk Among the Tombstones and Honest Thief – have a similar flavour to Bronson’s thrillers. Bruce Willis paid homage by starring in a remake of Death Wish (2018). Quentin Tarantino is an admirer too.

The star links two different worlds: the old Hollywood studio system in which he started his career, working with directors like Henry Hathaway and Andre De Toth, and the very different, more freewheeling US film industry of the 1970s and 1980s. He had a relentless work ethic, clocking up roles on TV and on the big screen, but rarely discussed what his work meant. As he told Ebert, “I supply a presence.”

In a movie career spanning close to half a century, Bronson didn’t get a single Oscar nomination, or even a sniff of one. Many of his films, especially those with Winner, were reviled by critics. Nonetheless, whether as part of an ensemble in The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape and The Dirty Dozen, or as the lead in Once Upon a Time in The West and Hard Times, his work endures. He remains the first point of reference for anyone making a revenge thriller today. One hundred years after his birth and almost two decades after his death in 2003, he is still the hardman’s hardman, the one the others all respect the most.

‘Death Wish 3’ is available on Amazon Prime

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks