Dancing, flirting, popping pills: A new wave of old-age movies are leaving behind tired, ageist stereotypes

From The Father to The Mole Agent, several films in awards contention this year are about older protagonists. At last, writes Geoffrey Macnab, they are being portrayed not as victims or objects of pity but as strong characters facing very different dilemmas at the ends of their lives

Dennis Dean is the classic movie hustler. He is good looking in his own weathered, craggy way and dresses sharply in a Hawaiian shirt and porkpie hat. He has the gift of the gab, too. The law is after him, so he’s decamped from California to Florida. He is not ashamed to tap old friends and acquaintances for money. Nor does he hide his main intention. Dennis is on the prowl for female company. He is looking “to meet some wealthy women and get set up for life”. His ideal partner will be pretty enough not to embarrass him in public and rich enough to fund a lavish lifestyle.

The lovable but very seedy Dennis is one of the subjects in Lance Oppenheim’s debut feature documentary, Some Kind of Heaven, which is out in the UK next month. You could imagine him being played by Richard Gere or Jean-Paul Belmondo. There is, though, one important point to note about this indigent latter-day American gigolo… he is well into his eighties.

At last, filmmakers are depicting older protagonists with a sense of mischief – and without the zimmer frames. Some Kind of Heaven is just one of many old-age movies that are either on release or shortly to reach cinemas and streaming platforms. Several are in the running for major prizes at the Oscars this year. They all have characters as complex and contradictory as Dennis.

Oscar favourite and multiple Bafta-winner Nomadland is a story about predominantly older people enduring a tough, precarious existence as modern-day nomads. It is vying for voters’ attention with The Father, in which the octogenarian Anthony Hopkins stars as Anthony, a proud old man wrestling with dementia and failing memory.

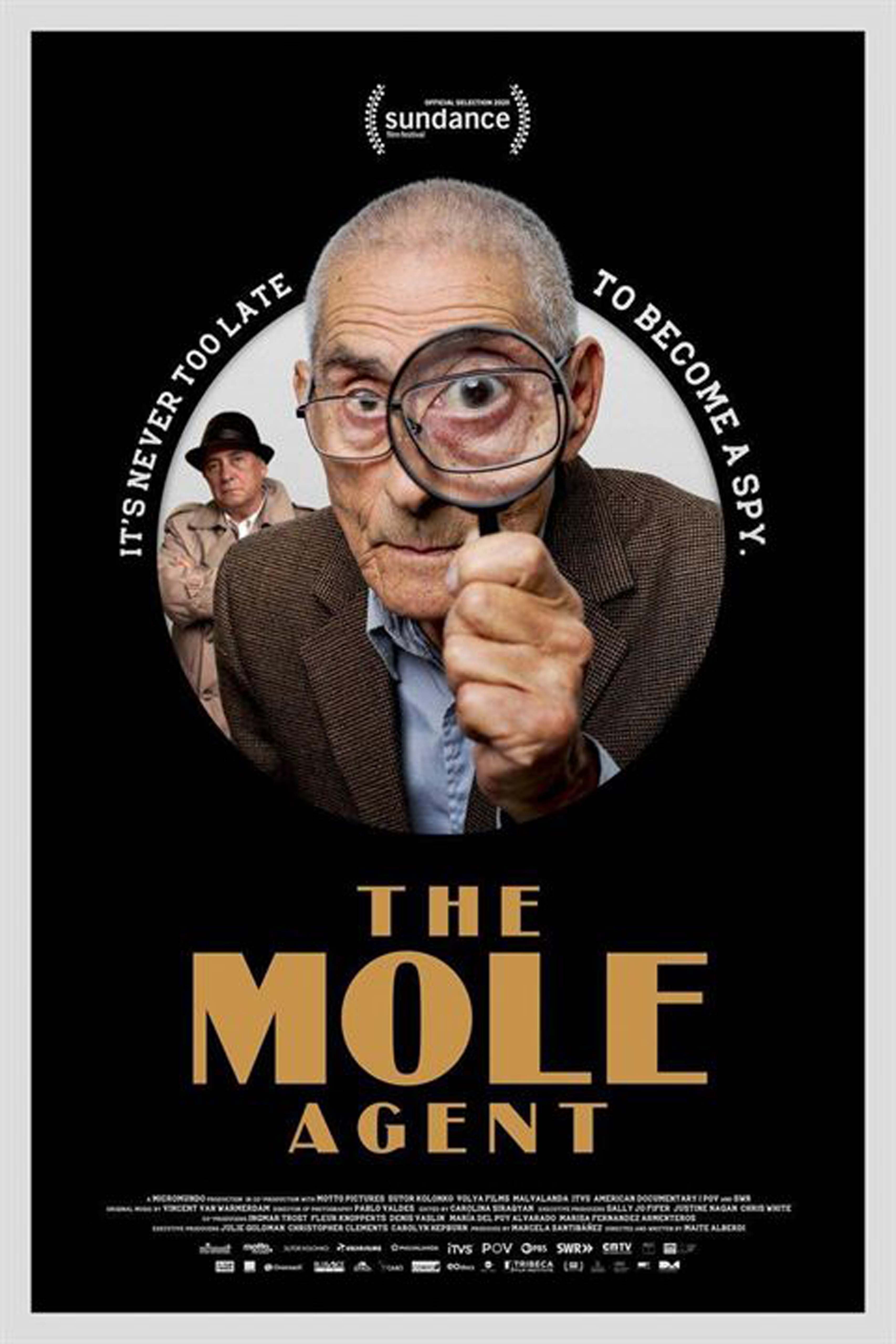

One of the favourites for the Best Feature Documentary award is Chilean director Maite Alberdi’s The Mole Agent, which follows the 83-year-old as he goes undercover in a nursing home to find out if the residents are being treated properly.

The excellent Oscar-nominated short documentary Colette features the 90-year-old former French resistance fighter, Colette Marin-Catherine, making an emotional pilgrimage to the concentration camp where her elder brother was killed by the Nazis more than 70 years before.

Oscar-nominated films aside, Netflix’s new superhero series Jupiter’s Legacy has Josh Duhamel as a silver-haired, straggly bearded superhero, Sheldon Sampson, one of an old guard of legendary but long in the tooth figures worrying whether the next, younger generation will live up to their feats.

Most of these new dramas and documentaries aren’t gentle, wistful Judi Dench or Maggie Smith comedies like The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel and Ladies in Lavender, which have become sure-fire money-spinners with the “silver pound” audience in recent years. Instead, they probe away at the rawest, most vulnerable sides of their protagonists while also showing the joys that they can still experience.

One of those joys is sex.

When she was preparing her new documentary, The Bubble, about the huge retirement community The Villages in Sumter County, Florida, Austrian director Valerie Blankenbyl decided not to focus on the STD scandal there a few years ago. That was when The Villages was dubbed the sexually transmitted disease “capital of the US”.

The Bubble (a world premiere this week at the Visions du Réel Festival in Nyon) has plentiful scenes of very mature couples drinking, dancing and flirting in the many bars and clubs found within The Villages, a community of 120,000 people.

“Ten women to every man, a black market in Viagra and a thriving swingers’ scene,” read the headline in one newspaper report about the community.

There are obvious reasons why STDs might be a factor in retirement homes like The Villages: the high number of bereaved or divorced single people, the general disregard of contraceptives and the easy availability of alcohol. Blankenbyl herself witnessed scenes of recently hooked-up octogenarians (“the cutest couples”) snogging like teenagers in love for the first time. However, as she told me, “there is only so much that little blue pill can do for you”. The desire may still be there but the flesh isn’t always willing.

As Blankenbyl saw it, the stories about the promiscuity of the residents have been whipped up by a media keen to startle the public with lurid accounts of OAP depravity in order to cover up its own embarrassment at the thought of older people’s romantic lives.

“I felt that these reports were made by journalists younger than the people who live in The Villages and are somehow shocked by the fact that people of a certain age are having sex, which I am not shocked about,” the director, who is in her late thirties, reflected. “Maybe that is the difference between a European view and an American view. I am happy that they are having sex and I hope that I will be having sex at that age as well.”

After a year of the Covid pandemic, in which elderly care home residents have perished in large numbers and been cut off from the rest of the world, it is a relief to hear about sex rather than death. Even if the stories are exaggerated, at least they don’t portray the old people as victims pressing their faces against the glass and waving forlornly at the relatives they are not allowed to touch and may never see again.

Filmmakers’ attitudes towards old age are clearly changing. No longer do the traditional ageist stereotypes persist. As Alberdi, the director of The Mole Agent, puts it: “We usually, in our society, speak about old people as a general group, a sociological brand. I have been seeing that there are so many ways to be old, so many possibilities, so many stories.”

The Mole Agent starts as an exposé of corruption and wrongdoing in the care home system but soon turns into a poignant study of old age itself, full of charm and graceful humour – and with plenty of flirtation and romance.

Many of the gnarled old travellers depicted in Chloe Zhao’s Nomadland are retired or jobless. Their spouses may just have died. Often, they can’t afford homes and so they live out of caravans. They’re on the breadline. They have a freedom, though, that younger, more comfortably-off friends and relatives lack. In some of the film’s most moving scenes, Zhao shows the camaraderie between the lonesome travellers who meet around campfires and will share food, medicine and information. At times, the film plays like an OAP version of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road or a more leisurely answer to Easy Rider with camper vans instead of Harley-Davidsons.

Anthony Hopkins may be ancient but even playing a role like his ageing patriarch in The Father, he remains the same formidable presence audiences know from The Silence of the Lambs or Richard Eyre’s BBC film of King Lear. He terrifies his nurses and carers, accusing them of stealing his watch when he has simply forgotten where he put it. He is stubborn and proud, refusing to acknowledge the slightest thing wrong with him. He uses his sly charm to get his way or to placate his relatives when they become exasperated by him.

Writer-director Florian Zeller’s achievement is to make Anthony’s epic battle against his own declining faculties as compelling as the struggles of other screen heroes against more conventional screen foes. It’s a performance full of rage and mounting despair but also of extraordinary tenderness.

Like The Bubble, 25-year-old Oppenheim’s Some Kind of Heaven is also set in The Villages retirement home in Florida, the director’s home state. It focuses on the experiences of four elderly individuals (among them the ne’er do well charmer Dennis) who, for different reasons, don’t find life to be the blissful experience that the brochures promised. Illness, drugs and delinquency cloud their lives.

What all these films have in common is that they treat their characters as flawed, passionate often querulous individuals whose lives are still full of contradiction and still worth examining. They’re not passive, dependent victims waiting to die. They drink, pop pills, have affairs and worry about money.

In some ways, it’s a surprising time for filmmakers to become fixated on old age now. One trend distributors and box office analysts noted over the last year, as the pandemic first took hold, is that older audiences have been staying away from cinemas. In those periods between lockdowns, when venues opened, younger cinema goers were buying most of the tickets.

Nonetheless, addressing old age is a way of continuing to harness the brilliance of actors like Hopkins and Glenn Close (Oscar-nominated at 74 for Hillbilly Elegy). Hollywood has ignored or caricatured old people for so long that there is plenty of fresh, untapped material out there. Writers and directors may have witnessed the travails of their own elderly parents and so can bring personal insight to their films.

Intense, serious drama like Michael Haneke’s Oscar-winning Amour (2012), in which Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva played the loving elderly couple, used to be notable for their infrequency. Now, it seems, filmmakers are finally growing up and realising that they can confront old age without being sentimental and silly or alienating their audience.

The Bubble is a world premiere at Visions du Réel, 15-24 April.

Nomadland will be available to stream on Disney Plus on 30 April and in cinemas from 17 May.

Some Kind of Heaven is released on demand on 14 May.

The Father is due to be released on 11 June.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks