After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art review – A show with enough great works to be worthwhile

The National Gallery’s show may present a well-known story as though it’s a new discovery, but many paintings are worth the price of admission

Apparently Impressionism evolved in a number of directions, each of which had a massive impact on art in the 20th century. Good Lord. Who knew? Well, probably the vast majority of the likely audience for this major exhibition at the National Gallery for a start.

The story of the great late 19th-century/early 20th-century revolution in visual perception – the subject of this show – is probably the most frequently told in art. It gave rise to some of the most genuinely popular art ever created. You may have heard of a bloke called Van Gogh. If it seems more than faintly risible for the National to be trying to spring this well-worn narrative on us as though it’s a big surprise – while bringing in all the hugely bankable artists that come with it – there is a backstory. This was to have been a joint exhibition with Moscow’s Pushkin Museum, which has some of the world’s greatest holdings of early modern art. A certain conflict put paid to that, and rather than cancel the National bravely decided to continue, supplementing masterpieces from its own collection with interesting loans from around the world.

After Impressionism aims to tell a geographically expanded story on what we’ve come to think of as Post-Impressionism (though it studiously avoids using the term), taking in not just the great modernist capital Paris, but parallel developments in Brussels, Barcelona, Berlin and Vienna.

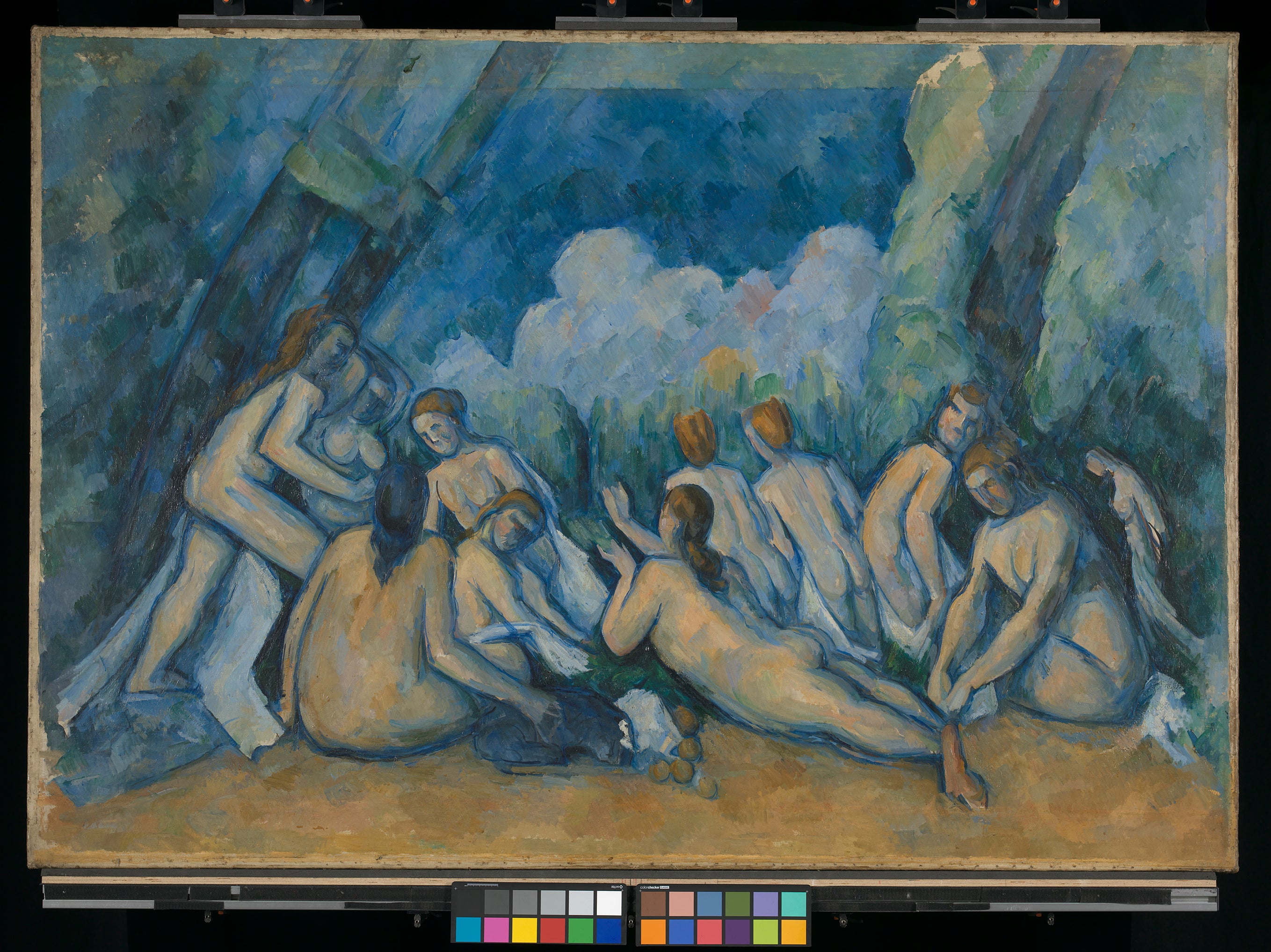

The show sets out its stall in the first room with Cezanne’s monumental canvas The Bathers (1894-1905) seen beside the towering plaster-cast version of Rodin’s Balzac (1898). The great writer’s radically simplified outline, swathed in his plaster-soaked dressing gown, looms over the room like some belligerent ghost. The fact that the Cezanne is from the National’s own collection and has only just been highlighted in Tate’s Cezanne show is beside the point. These are incontestable masterpieces that radically reimagine the human form while glancing back towards the classical tradition. But the exhibition muddies the waters by throwing in a work by the quirky classicist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. His frieze-like image of nymphs and goddesses in a landscape brings a distinctively different flavour to the conventions of academic classicism. Is it world-changing? Absolutely not.

The show wants to demonstrate how much “new generations of painters and sculptors brought every tradition of image making into question”, while glancing nervously and reverentially over its academic shoulder to the traditions they were supposedly demolishing.

The three artists who the exhibition defines as the leaders of this new post-impressionist art – Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cezanne – are allocated five works each, and they don’t disappoint. The Van Goghs, mostly relatively little-seen landscapes, pack extraordinary passion and energy into smears of paint so fresh they look just squeezed from the tube. The massive over-exposure of the Van Gogh “style” has done nothing to blunt these paintings’ impact.

You could hardly have a better example of why Cezanne was to be massively important in the 20th century than Madame Cezanne in a Red Dress (1888-90). It’s a Cubist painting 20 years before the event: at once fragmentary and monumental, as though you could reach in through the frame and grab hold of the artist’s wife.

The wall text goes to great lengths to both criticise and apologise for Gauguin’s Nevermore (1897), a near life-size painting of a naked underage Tahitian woman. These tortuous explications would carry more weight if they felt sincere, and if Gauguin’s foibles hadn’t already been hauled over the coals for decades. Of far more concern is whether this is a good – never mind a great – painting. The four accompanying paintings from his Brittany period are far more convincing in their primal emotionalism.

Edgar Degas is permitted among the show’s big boys with the fabulous Combing the Hair (1896) – another work from the National’s permanent collection that never loses its power. But Georges Seurat, whose pointillism – breaking light into primary-coloured flecks of paint – was one of Post-Impressionism’s most influential departures, is demoted to a room on “Different Paths”. Toulouse-Lautrec, another key figure, is represented by only two works, neither of which does him justice.

“By the 1880s,” the wall panels tell us, “there were widely divergent stylistic paths available to radically minded artists” – which sounds painfully dry, as though younger artists were adopting these “styles” as calculated career moves. Emile Bernard’s The Pardon (1888) shows Breton women on a strong, semi-abstract green background that looks heavily indebted to Gauguin. Yet Bernard, as the text concedes, adopted this approach before the slightly older Gauguin – Bernard argued, indeed, that Gauguin had stolen his technique. Paul Serusier’s exquisite semi-abstract The Talisman (Landscape in the Bois d’Amour) (1888), meanwhile, was effectively dictated to him by Gauguin in what amounts to an expressionistic painting lesson and a piece of proto-conceptual art.

These works really needed to be seen alongside the Gauguin paintings to give the sense of a tumultuous, unpredictable moment when everything was happening at once. But the show is too caught up in its hidebound, academic categories to capture the free movement of forms and ideas that this period was all about.

Where the exhibition does depart from the precedents set by endless previous shows on this period is in extending its attention from France to other European capitals. And it’s here that it really gets unstuck.

Brussels justifies its inclusion only through James Ensor’s startling, proto-Surrealist Astonishment of the Mask Wouse (1889). Theo van Rysselberghe’s full-length portrait Alice Sethe (1888) is a cringe-making mixture of Seurat-style pointillism and cloying academicism. Equally, I doubt the show would even have considered Barcelona as a Post-Impressionist capital if it weren’t for the contribution of the young Pablo Picasso. His green-faced portrait of Gustave Coquiot (1901) adeptly synthesises everything the 20-year-old painter admired in Van Gogh, Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec, with a demonic verve none of his exemplars came close to achieving. Of the other works in this section, the less said the better.

In Berlin, works by Max Liebermann and Lovis Corinth employ loose “impressionistic” brushwork, but with dour colours redolent of old-school Germanic academicism. This section is only elevated by Edvard Munch’s stark and agitated The Death Bed (1895), with its washed-out skull-like faces. The artist was based in Germany in this pivotal period. Vienna is represented by two prime works by Gustav Klimt, both full-length portraits of women, though they’re a reminder, with their whiff of high-class set design, of why Klimt’s mannered Mitteleuropean art nouveau doesn’t quite make it into art’s front rank.

After so much mediocre painting it’s frustrating to find the early phases of outright modernism – Cubism, Fauvism, Expressionism and early Mondrian – crowded into a cursory final section labelled “New Terrains”. Wassily Kandinsky’s transcendent paintings from his 1908 sojourn in the Alpine village of Murnau are some of the great breakthrough paintings of early modernism, though Bavarian Village with Fields (1908) is far from the best. The Picasso cubist portraits are fine, though their inclusion feels a touch nominal. Still, it’s hard to entirely dismiss a display that includes Picasso’s delightful Nude Combing Her Hair (1906), Matisse’s exquisite The Riverbank (1907) and the three sublime works by the underrated Andre Derain that close the show. His wildly decorative The Dance (1906) deserves to be far better known. And after its use on this show’s poster, it certainly will be.

For all its shortcomings – and I can guarantee I won’t be the only one grumbling – this show brings together enough great works to qualify as essential. Including bad stuff at least reminds us why the great stuff is great. That contrast made me feel excited all over again about a turbulent but exhilarating moment, when every possible artistic value was up for grabs.

National Gallery, from 25 March until 13 Aug

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks