Alice Neel: Hot off the Griddle review – easy on the eye portraits from an artist with guts

The New York portrait painter gets her biggest UK exhibition to date in a show that looks at her fascinating life as well as her art

An 80-year-old woman looks back at us wearing nothing but a pair of glasses and a “screw you if you don’t like it” expression. This stark-naked, bulges and all painting was the first self-portrait by an artist who feels very much a figure for our times, Alice Neel. The fact that she’s been dead nearly 40 years seems almost beside the point.

A communist feminist who rejected her middle-class New England roots, Neel (1900-84) married a Cuban and was investigated by the FBI at the height of the Cold War. She was dubbed the “court painter of the underground” for her portraits of artists, activists and, not least, her poverty-stricken neighbours in New York’s Spanish Harlem. Yet she’s been omitted from survey after survey of 20th-century American art. Over the past decade, however, the standing of Neel’s defiantly quirky portraiture has gone through the roof. Not only does her work befit an art world trying to become more inclusive – she looked beyond portrait painting’s straight, white conventions from a woman’s perspective – but it is highly accessible. It’s about things that art doesn’t deal much in these days, but which most of us still find important: people and their personal stories – all set against the backdrop of New York in its most culturally explosive era.

The Barbican’s exhibition – Neel’s biggest in Britain to date – is clearly out to canonise her as an all-time great, with an emphasis on Neel as a personality as much as a painter. Starting with that naked self-portrait, which is given a room to itself, Neel’s pronouncements are blown up large on the walls – “I don’t paint like a woman is supposed to paint” – with lots of great photographs and archive film, and wall texts that are much more chattily biographical than you’d expect in a serious art exhibition, where such things tend towards the po-faced.

Yet on balance, this personalised approach feels only fair. Would we, for example, be as moved by Van Gogh’s paintings if we didn’t know his tragic back story? And Neel’s story is well worth hearing.

Born into a conservative Pennsylvania family who reminded her continually she was “only a girl”, Neel decided early on that she “couldn’t stand Anglo-Saxons”. She found her feet in art school in Philadelphia where she was given the freedom to paint “more or less as you wanted”, and met and married Cuban artist Carlos Enriquez Gomez. It was the first of many unpredictable relationships in a life of eccentric individualism in which she went her own way regardless of the emotional and financial costs. And by all accounts she never stopped talking.

Early paintings from the 1920s are very assured in a loose, broadly post-impressionist style. But after a succession of major life events – a breakdown following the death of her first child, her former husband’s removal of the second to Cuba, and her own move to Greenwich Village, hotbed of New York bohemia – the appearance of her work changed dramatically.

The bizarre Joe Gould (1933) shows a well-known Greenwich Village eccentric with three sets of genitalia – a comment on his “inflated sense of his own virility”. Bronx Bacchus (1929) features a couple sitting blankly side by side, the man, with an absurdly long stringy penis (generally there are a lot of penises in Neel’s work) picking up a bunch of grapes. These feel like images from the edge, infused with a crazed proto-Beat creativity that simmered in the garrets of the Big Apple, but with Neel’s own distinctive eccentric spin.

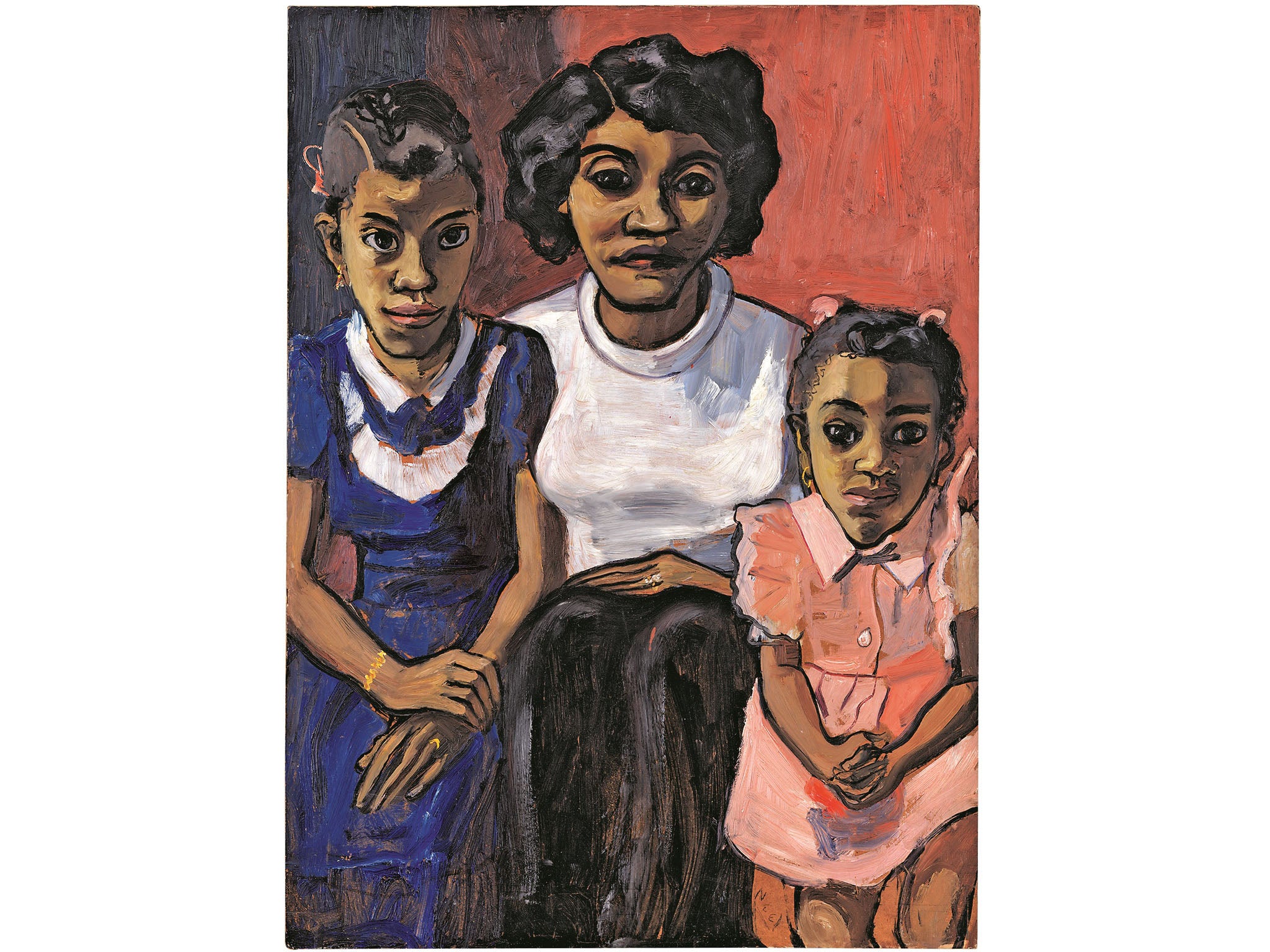

But it was with her move to Spanish Harlem in 1938 that Neel got properly into her stride with portraits of her neighbours that attempted to “reveal the inequalities and pressures shown in the psychology of the people”. Georgie Arce No 2 (1955) shows a street child she befriended looking challengingly back at us holding a large unsheathed knife. Black Spanish-American Family (1955) pulsates with bright-eyed energy: the two little girls look hungry for life, while their mother already has an appearance of weary resignation.

You’d never imagine looking at Neel’s paintings that she was working in the middle of some of modern art’s most dramatic developments: Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Fluxus, Happenings – the list goes on. Neel consciously rejected the large scale of American abstraction, wanting to “trot back to human size and human feelings”. Her formative era, indeed, was the economically desperate, politically polarised Depression years, the mood of which continued into the Cold War’s anti-leftist paranoia, and into her own paintings.

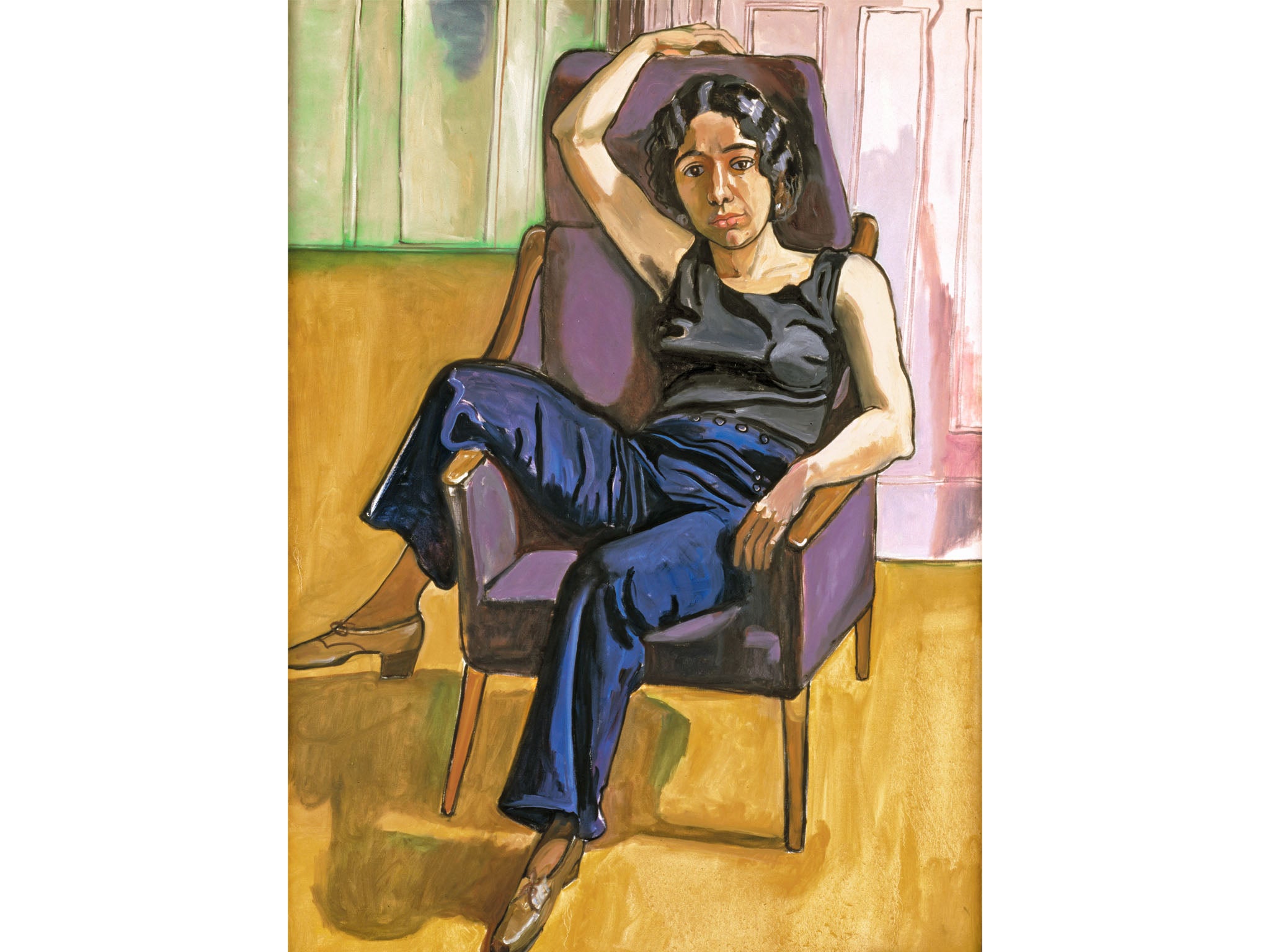

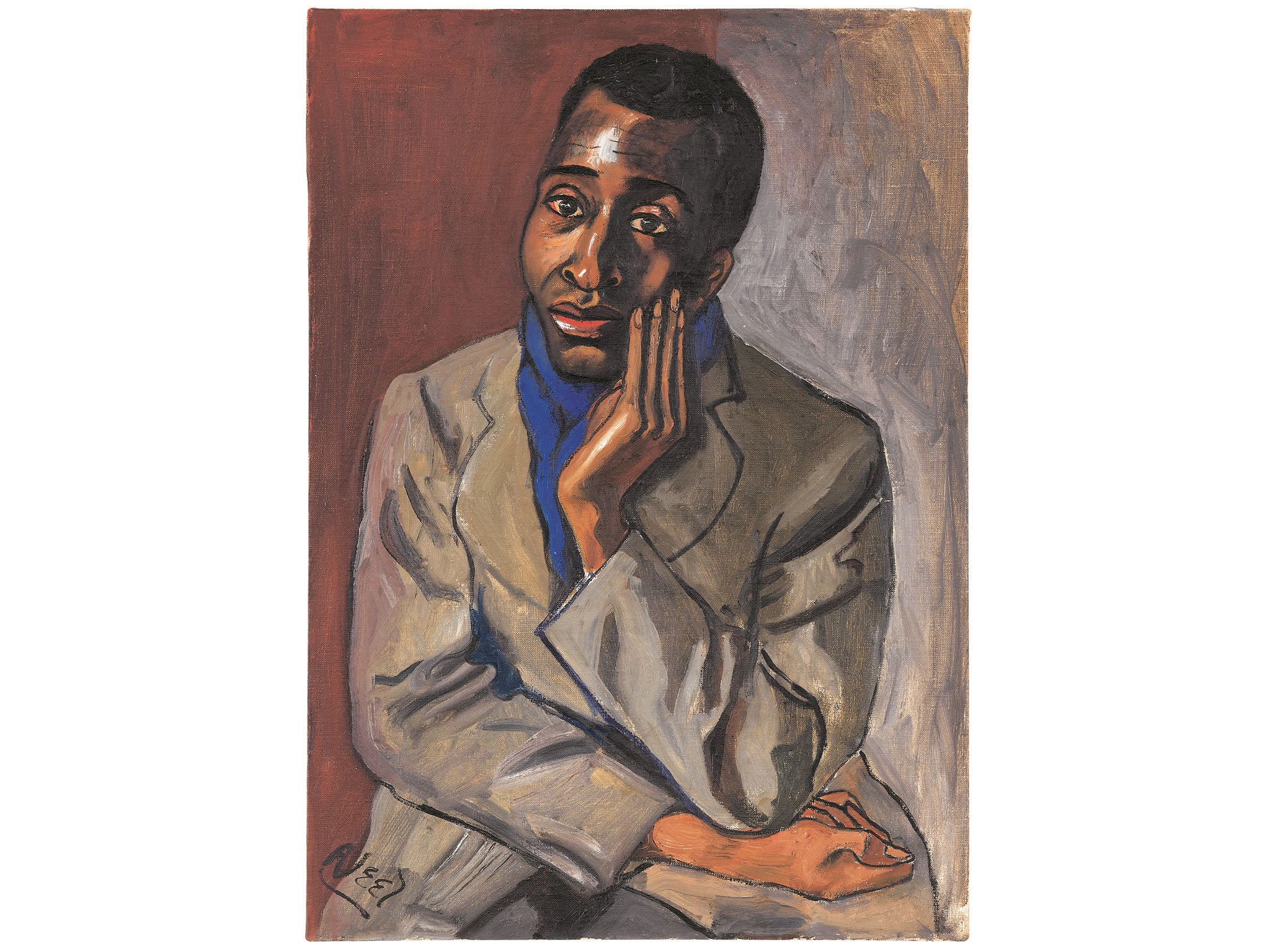

While the FBI wrote Neel off as a “romantic, Bohemian-type communist”, she produced fantastic portraits of her fellow activists. In Mercedes Arroyo (1952) the Puerto Rican independence leader stares skyward as though towards some visionary future. Neel’s partner of the time, filmmaker Sam Brodie (1945), is seen in stark profile against a wintry sky from which ghostly faces appear, while sociologist Horace Cayton (1949) is a quasi-Cubist study in muted blue-greys and lilacs. It’s as though Neel is trying to work out what a really penetrating, politically committed portrait should be, and coming to a different conclusion each time.

But in her portrait of intellectual Harold Cruise (1950), with its strong outlines, she seems to be already evolving the signature style of her mature work, the paintings for which she is best known. It’s a strong painting, but slightly literal, even illustrative in comparison with the others. The works in the Barbican’s two large downstairs galleries, devoted to the latter part of Neel’s career, are very much in this mode, with forms delineated in vigorous but slightly stylised outlines in black or blue. Neel has found her way of doing things, and she pursues it very confidently, bringing us a whole range of mostly affluent Alternative Society types from the late Sixties to the early Eighties. She still has the capacity to give a subject an expression that makes you jump – mostly very young women, such as the slightly spooked-looking Julia in The Family (1970). But the sense of desperate exploration seen in the early work is gone.

Gerard Malanga, Andy Warhol’s long-term assistant and lover, sits with his leg cockily thrown over the arm of his chair, but the treatment of his features has a graphic, illustrative quality – as indeed has Neel’s treatment of her own appearance even in that courageous nude self-portrait with which the show begins. The “wonky” quality, which the show’s catalogue notes in her work, has become a mannerism.

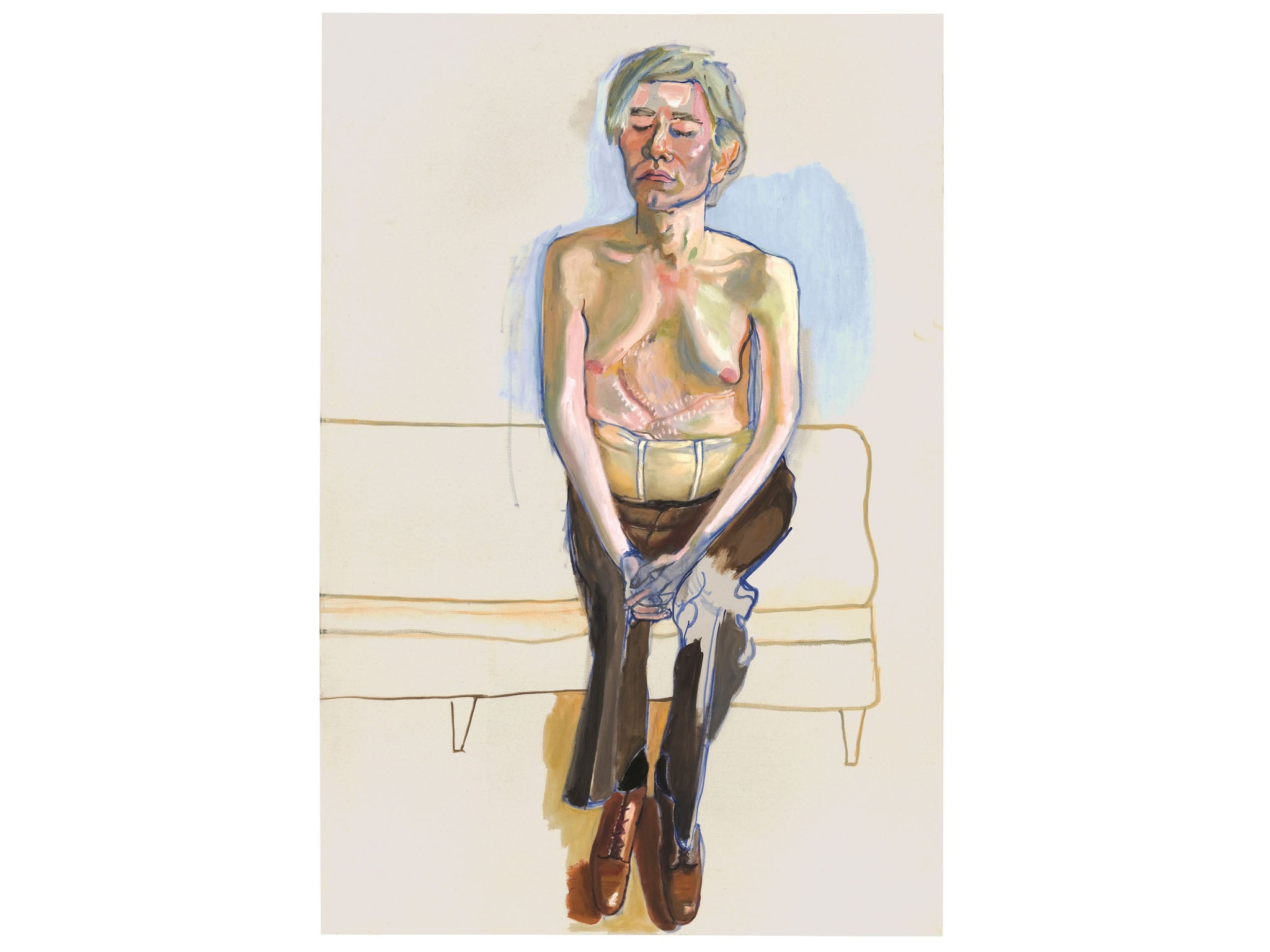

Even a painting of Warhol himself, bare-chested after his shooting by Valerie Solanas, exposing his scars and surgical truss – an image that should be shocking – feels almost cosy.

The show makes much of Neel’s affinity with outsiders. Indeed, it’s great to see gay couples, such as David Bourdon and Gregory Battcock (1970), publicly comfortable in each other’s company, at a time when homosexuality was still illegal in many American states. Gregory is smartly suited, while David looks comically quizzical in singlet and yellow briefs. While Neel, indeed, “creates a space for people to reveal themselves”, as the curators claim, these are figures from the upper echelons of the art world. They’re not one step away from the gutter or prison like many of the people in her earlier paintings. There’s little sense of risk.

These paintings are very easy on the eye. If they don’t come quite into the category of “great”, they compensate with a good gossipy sense of a time and place. As for Neel the historical personality, who is as much the subject of this entertaining exhibition as Neel the artist, I think it would be hard to come away without applauding her sheer guts in keeping going, pursuing her vision through the best and worst of times.

Barbican Centre, until 21 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks