How we found success with our Nineties boy band – in our fifties...

Hanging out in Camden and supporting Blur at the height of Britpop... Michael Brown thought his band, Giant Killers, had made it, but then they were dramatically dropped from their record label. How surprising then it has been to be ‘rediscovered’ in midlife

Like many young lads growing up in the North’s grittier outreaches, I had a dream. It will be a familiar one for those of a poetic persuasion with few outlets to express it. I worked in a factory in Grimsby, but I dreamed of moving to London and being in a band. And one day I just did it. Me and my best mate Jamie upped sticks, moved south and tried our Northern luck.

We nearly made it too. No, honestly we did. We landed two major record contracts, went on TV, heard our songs on the radio, and toured with bands like Blur, Squeeze and Nick Heyward. We were even a sticker in Smash Hits.

And then we weren’t.

Dumped by our label for not selling enough music (in the Nineties you had to sell hundreds of thousands to go Top 10) – overnight we became unloved and commercial failures and consigned to the footnotes of music history.

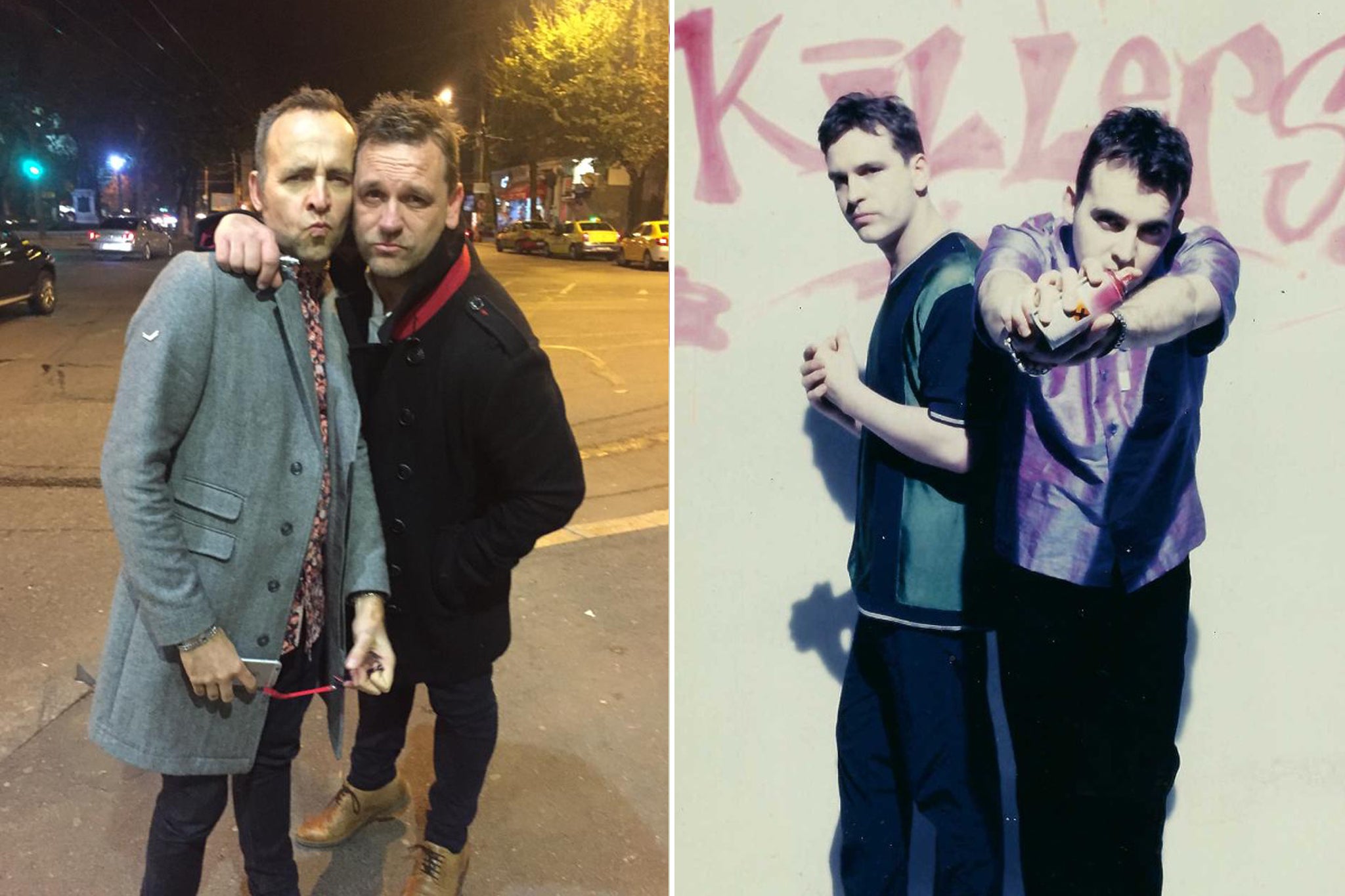

Which is why today Jamie and I are in a constant state of surprise to see an album we wrote three decades ago suddenly being lauded in today’s music press. Having long put our dream to bed like a reluctant child, we’re watching this unfold as men both now in our fifties, with “proper” jobs and real children to look after.

“The world has been worse off this last quarter-century by not having these deftly crafted indie gems in mass circulation.” So said the former editor of Kerrang, now host of the popular James McMahon Music Podcast. And from the UK’s most credible music bible, John Robb’s Louder Than War: “‘Around the Block’ is surely the best song The Lightning Seeds never wrote.”

So, how did we get here?

Jamie and I were proudly working-class dream-chasers with no academic qualifications. We first met when I worked in a Grimsby double-glazing factory and he was cleaning the town’s windows – I made ’em, he polished ’em. But it was an advert to join a band that brought us together. It became our first musical adventure together – the band was called Illustrious.

I remember his first words to me – “I hear you’re looking for a singer,” he said, in a way that suggested the search had ended. I recognised a kindred spirit. Other than an unshakeable self-belief (bolshie Northerners you see) neither of us had much going on: Grimsby wasn’t the centre of the music universe like Manchester was, and all our mates were being exploited by the “Youth Opportunities Programme” for £23.50 a week. We knew heading south to chase a brighter horizon than is normally afforded to people like us, the kids from terraced houses, would be our only escape.

We launched ourselves during the late Eighties. We travelled to London and hustled and won gigs in places like Harlesden’s Mean Fiddler, Islington’s Powerhaus, and the famous Marquee Club – venues rammed with young people from the provinces with something to prove.

At first, we’d drive back to Grimsby in our battered Ford Transit, and if that broke down, as it often did, my dad’s old Datsun, but the gigs got so frequent we ended up just staying.

Our first address was a mattress in a grim Finsbury Park room with no curtains. We sofa-surfed in Tooting, Archway, Holloway and Hackney – the then rougher parts of the city. This London was not paved with gold, but hey, we were from tough Grimsby so we weren’t fazed.

And we were documenting it all in our songs, just as our heroes had done. Wham’s “Wham Rap!”, The Specials’ “Ghost Town”, Elton’s “Saturday Night’s Alright for Fighting”, all The Jam songs – all about working-class kids like us dreaming bigger than they were told they were allowed to.

We were completely self-taught, with Jamie crafting melodies to the lyrics I wrote, both constructing motifs for the other instruments using a guitar and a tenor sax.

Our songs told stories of misspent youth and life on the council estates. We lived on our wits, charming our way into art openings, record company showcases, and press launches. We went to meet the “right” people, but mainly for the free food and booze. Because we were on benefits too.

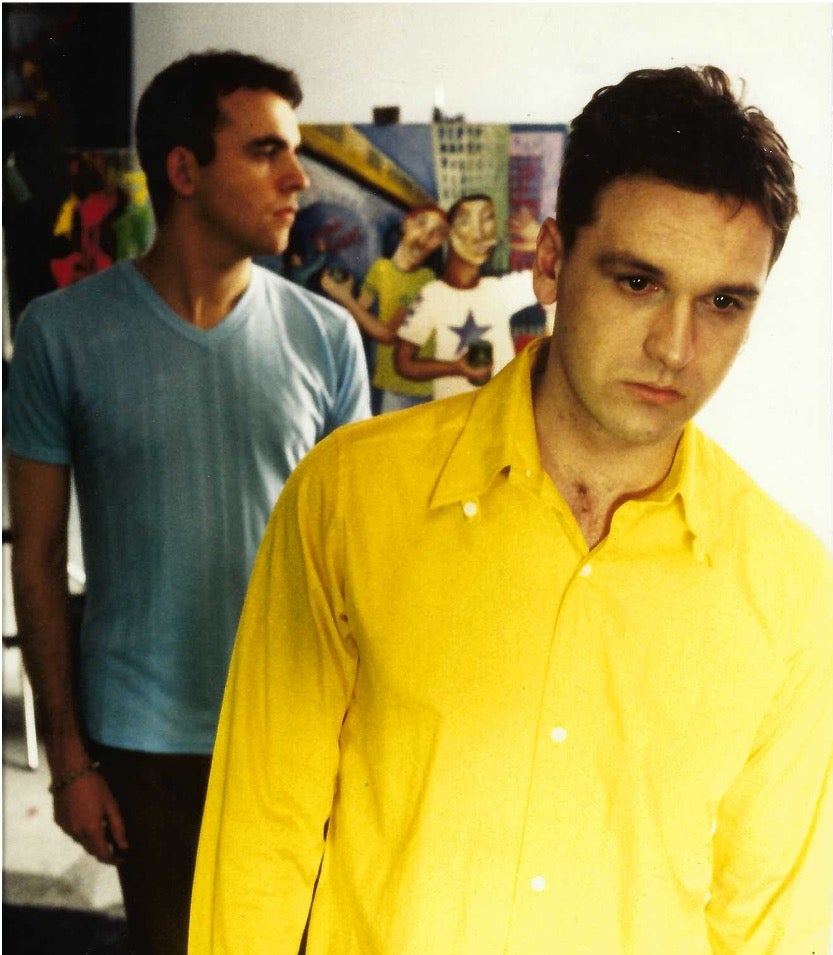

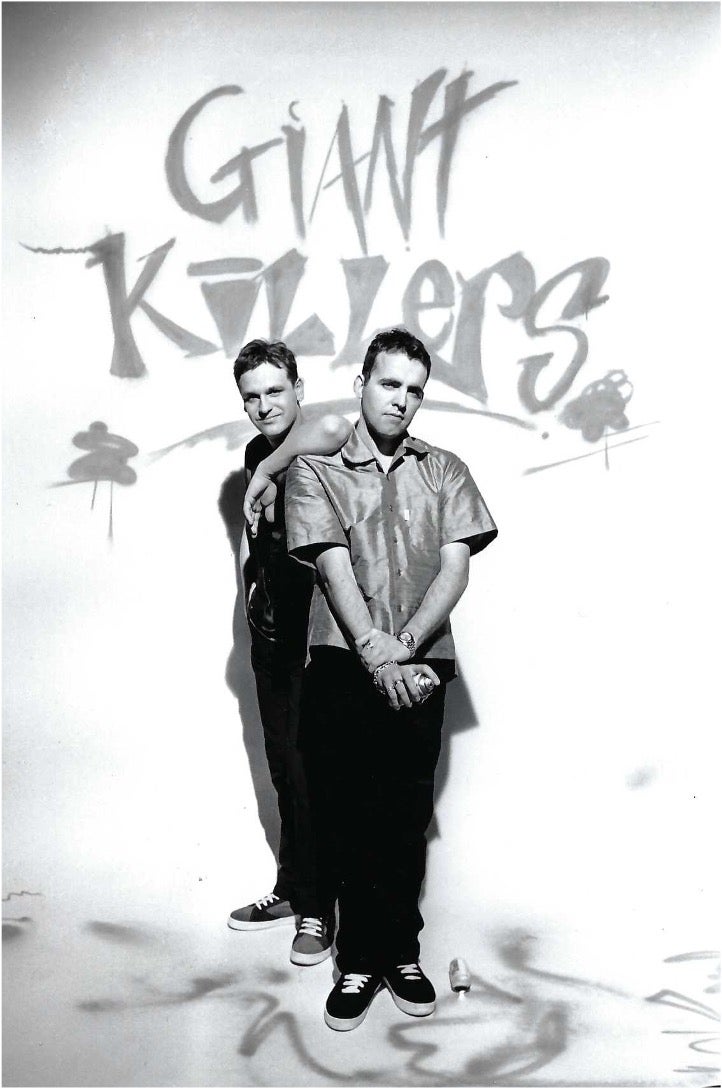

By the time Britpop arrived, we were established in our second musical incarnation as Giant Killers, hanging with the Britpop crowd in Camden’s Good Mixer.

We got to know everybody from playing in the industry football kickaround in Regent’s Park every weekend. It was organised by the late Andy Ross, head of Food Records who signed Blur and Jesus Jones.

Some of the big journo names of the day turned out – Simon Price, Johnny Cigarettes, Chris Roberts, loads of A&R folks and pop stars; Damon Albarn played, the guys from Menswear, even Jarvis Cocker put in a shift when we did a tournament at Mile End. A pre-fame Sophie Ellis-Bextor popped along for post-match drinks.

We’d already won and lost one major record contract, so as the Nineties got underway, my brother Andy and our mates Matt and Daz helped us set up our own tiny label.

We were savvy – we worked out we needed a distribution deal to get our record into the shops if demand was sufficient. To create that demand, we persuaded Nick Battle, a radio plugger from Sheffield, to help bash the phones to radio stations – and between us, we got seven plays on Radio 1.

We didn’t sell much, but it generated new major label interest, who were surprised to find us making headway off our own backs. Inevitably, there was an offer from one of them (Arista). We thought we’d won the lottery.

Without that single fixation that drove our younger selves, our lives became complex and layered – just like other humans. Decades came and went

Naivety! We’d merely bought the ticket. There was no huge signing fee. Arista invested into recording our music, but there was nothing spare to live on. When we appeared on BBC’s Going Live! to nine million people, the show’s production assistant sent us a Tupperware box of dinner-party leftovers – experience had taught her to recognise artists in need. Maggie Robinson, if you’re out there, thank you. We’ve still got your Tupperware if you need it back.

We made mistakes. Jamie and I drove everything forwards, but we let the artistic control slip and got cut out of the songwriting. An eyes-off-the-ball moment caused the demise of Illustrious and our record contract.

We could have gone home, but hitting the canvas without throwing a few more punches on the way down? That wasn’t how we’d been brought up.

We (just) had to write an album, sign on (again), and find somewhere to live (again). Our then manager, Jonathan Cooke, stepped in, letting us live for free in an empty office he had spare. It was back to sleeping on floors, but the address was good – Marylebone High Street. It became the birthplace of Giant Killers, another hard-won major label deal with MCA, and where we doubled down on our songwriting, turning again to our tribe for inspiration.

The songs on Songs for the Small Places celebrated how where you come from shapes your outlook. They captured the tensions caused by a lack of opportunity, but how that also brings with it qualities of resilience and community.

We came of age knowing failure is a more likely outcome than success, but it’s all an opportunity to grow. We did our growing up in Grimsby and then London – we experienced pain in leaving people and places we loved behind, sometimes it felt like a betrayal, maybe some back home felt that way too. Being in bands and on telly – it’s just showing off, isn’t it?

I was 30 in 1996 when we got dropped by MCA after our second single went nowhere. This time we saw things differently. The real world beckoned and it was time to pack away my VHS tapes of old recordings and put other things first – to accept my fate as Mike the Minor Pop Star, as a long-standing friend had jokingly dubbed me.

Me and Jamie went on to get “proper” jobs, mortgages, have kids even. We moved out of That London and became separately successful in the world of business. Without that single fixation that drove our younger selves, our lives became complex and layered – just like other humans. Decades came and went.

And then, still friends in our fifties, we were reminded of the live power of our songs when a friend persuaded us to reunite for his 50th birthday gig in Leeds. Hmm, we thought, maybe we should do something about this. We’d been on a long journey to get the rights to our compositions back anyway, and we still had this little record label of our own. This collection of songs we’d written in our twenties finally were given a new release – and this time, Jamie and I are in control.

It has been moving to watch these songs take on a new life. As one reviewer said, they are so poignant because we were boys writing about the men we might become – a kind of nostalgia for the future. This is personal stuff, but as the reviews are now saying, the themes are universal, whether you’re from Grimsby, Gdansk or Ghana.

Our record is climbing the charts, but we’re not young men any more. Songs for the Small Places is part of our legacy. “The Giant Killers’ sound may be more necessary now than ever,” said one enthusiastic reviewer. An “exceptional debut”, said yet another. Well, it took longer than originally anticipated, but now it seems we’re back. My children, now in their twenties, can hardly believe it.

‘Songs for the Small Places’ by Giant Killers is out now on Little Genius Recordings

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks