Outtakes or must-haves? Legacy acts won’t stop releasing music – have we reached ‘peak archive’?

As Neil Young, Bob Dylan, Elton John and others keep serving up unreleased songs and demos, Stevie Chick looks at the artists whose ever expanding back catalogues test their fans’s patience – and purchasing power

It ain’t cheap to be a Neil Young completist right now. His latest release Dume is the maverick singer-songwriter’s 20th album in five years. But the 78-year-old isn’t experiencing some late-career surge of creativity: 16 of those 20 albums are entirely composed of material recorded many years earlier. And Young’s not the only baby-boomer superstar scavenging nuggets from his closet to share with his fans – The Beatles, Joni Mitchell, Elton John and many more are at it too. Everyone, it seems, is glorying in the era of “peak archive”.

Back in the day, the release of unreleased old recordings was a shadier business, with labels often ripping off fans and artists alike as they scraped every barrel they owned. Artists who’d left one label and found success elsewhere might discover former paymasters repackaging their old dregs as new material. When Aretha Franklin became the queen of soul following her mid-1960s move to Atlantic Records, her previous label Columbia issued numerous compilations of discarded songs from her six underwhelming years with them, competing with her genuine new releases.

The premature passing of a star often provoked an avalanche of outtakes (and still does: see the posthumous Kurt Cobain industry). Jimi Hendrix died while still conceiving the sequel to his 1968 masterpiece Electric Ladyland. This unfinished work soon surfaced across a series of posthumous releases of wildly varying quality. The marvellous 1971 release The Cry of Love debuted future fan favourites like “Angel” and “Drifting”, but by 1975’s Crash Landing his label was hiring session musicians to patch up otherwise unreleasable Hendrix fragments. The results were often dire.

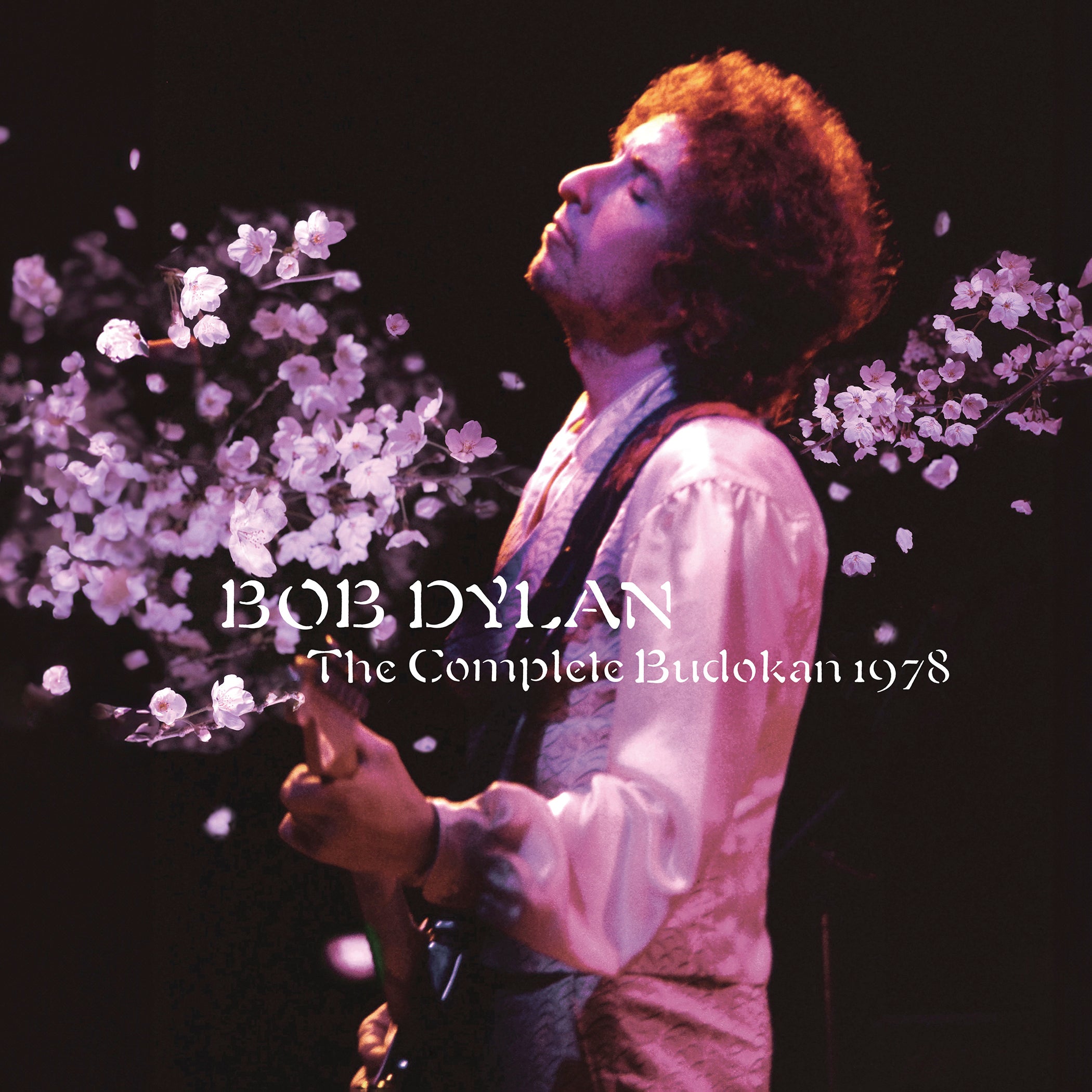

When the compact disc arrived in the 1980s, labels began attaching unreleased outtakes as bonus tracks to persuade the faithful to repurchase albums they already owned on older, less shiny formats. Then, in 1991, Bob Dylan initiated his Bootleg Series, its 17 volumes (and counting) of unheard music offering a deeper understanding of the enigmatic Bob. The Beatles, meanwhile, released the three-album series The Beatles Anthology to tie in with the 1995 TV documentary series of the same name, sharing unreleased recordings and alternate versions from across their career.

Where Dylan and The Beatles go, others inevitably follow, and a lucrative reissues industry prospered, until the internet spoiled everybody’s fun by making rarities widely available. But the recent vinyl renaissance has seen labels and artists alike searching their archives for material to feed this uptick in demand. This market has reawakened just as rock and pop’s legacy artists – the generation that once hoped they’d die before they got old – have reached retirement age, announcing their “farewell tours” and selling off their master recordings and publishing rights for hundreds of millions of dollars.

These archival releases are a further symptom of this fire-sale mentality, but they’re not simply cash-centric cynicism. Like Prospero in The Tempest, these stars are preparing to hang up their magic forever, looking to shore up their legacies and shape how they’ll be remembered. Elton John’s luxurious, outtakes-stuffed 50th anniversary box-set of his 1971 album Madman Across the Water argued that, beneath the glam trappings, oversized glasses and Tantrums & Tiaras-style scandal, Elton is an artist of depth and merit – that you couldn’t know the real Elton until you heard the piano demo of “Levon”, its Americana affectations shining even brighter when shorn of the album version’s lusher orchestrations.

These retrospective releases have been boosted by AI technology enabling producers to rejuvenate previously unlistenable ancient recordings – such tech revived a long-lost Ravi Shankar performance at Woodstock for a recent 38-CD box-set chronicling the 1969 festival. The surviving Beatles used it to repair a damaged John Lennon demo they used as the basis for the group’s “final” single, last year’s “Now and Then”. The software also enhanced hours of outtakes from the maligned 1970 movie Let It Be that Peter Jackson sculpted into his revelatory 2021 documentary The Beatles: Get Back. Perhaps the most illuminating archival project of all, the eight-hour series weaved together outtakes and in-studio chat, gifting us fans an unrivalled insight into the group’s unique relationship – and also their unravelling.

“Peak archive” isn’t all good news, however. The world’s few remaining vinyl pressing plants are buckling under the weight of retro wax, huge backlogs meaning younger artists on smaller labels often struggle to get their music pressed up. It’s a stultifying, frustrating situation that must leave many feeling like The Clash did almost 50 years ago, calling for “no Elvis, Beatles or The Rolling Stones” in 2024.

But for us armchair pop historians, revelling in outtakes and unreleased concert tapes that cast new light on our heroes and illuminate their creative processes, this is a boom time. Rediscovered watershed John Coltrane concert recordings like A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle and Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy alone redeem any reissue rip-offs clogging the racks. Fleetwood Mac’s series of “alternate” versions of their landmark 1970s and 1980s albums are a revelation, spotlighting the production brilliance of the group’s mercurial former singer/guitarist Lindsey Buckingham.

The artist who’s making the most of ‘peak archive’ remains Neil Young. A wilful, wayward artist who spent his 1970s and 1980s recording and then shelving countless projects, as chronicled by Jimmy McDonough’s biography Shakey, Young had long promised to open his voluminous archives to his fans

And it isn’t just the same old white male rock heroes benefitting from these purges of the archives. Joni Mitchell’s genius was underestimated in her day by a misogynist rock media that preferred to revere her blokier contemporaries. But her subsequent critical renaissance has prompted an ongoing series of Archives box-sets, uncovering priceless treasures like her original 1963 audition tape for Saskatchewan radio alongside key demo and live recordings. Alice Coltrane was disregarded by much of the jazz press when she pursued her own fearless career in the wake of husband John’s 1967 death, but recent years have witnessed a reappraisal of her exhilaratingly challenging output, kickstarted by Luaka Bop’s excavation of her 1980s devotional music, World Spiritual Classics Volume 1: The Ecstatic Music of Alice Coltrane Turiyasangitananda. A new undiscovered live tape from 1971, The Carnegie Hall Concert, is one of this year’s most anticipated jazz releases.

But the artist who’s making the most of “peak archive” remains Young. A wilful, wayward artist who spent his 1970s and 1980s recording and then shelving countless projects, as chronicled by Jimmy McDonough’s biography Shakey, Young had long promised to open his voluminous archives to his fans. The project began with 2009’s The Archives Vol 1 1963–1972, a frankly ludicrous box set that used cutting edge Blu-ray and DVD technology to present fans with a virtual filing cabinet stuffed with rarities, which later morphed into an online subscription service (with accompanying app) offering a wealth of music and ephemera. It’s only snowballed from there. Each subsequent release in Young’s Archives series has presented another crucial piece in his jigsaw puzzle, including key unheard live recordings from throughout his career (particularly recommended: Somewhere Under the Rainbow, a poorly recorded but riveting concert from 1973, capturing Young at his most anguished and unhinged during his infamous Tonight’s The Night tour).

Even more compelling are the albums he compiled and then shelved back in the day, the likes of Homegrown (a tortured 1975 set chronicling the decline of his relationship with then-wife Carrie Snodgress), Hitchhiker (a masterful 1976 acoustic album his label rejected as sounding too much like demos) and Chrome Dreams (an early – and superior – version of what became his scattered 1977 set American Stars ’n Bars) composing an alternate-reality vision of Young’s discography.

“I’m fascinated by time travel and things like that,” Young told Uncut’s Jaan Uhelszki in 2007, ahead of the Archives project’s debut. “I’m such a collector that I have so much stuff.” And while our wallets are stinging, we devoted fans remain grateful that our beloved Neil continues to open his archives to us and further illuminate his legend.

Neil Young’s ‘Dume’ will receive a standalone vinyl release via Reprise on 23 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks