‘It went f***ing nuts!’ The Beatles did it – but what does it really take for a British act to break America?

Sixty years ago The Beatles blasted out of a smoggy England to set America ablaze with a string of incendiary slots on ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’, throwing down the gauntlet for future British guitar-slingers. Michael Hann speaks to Bush, The Beat and Def Leppard about their wild days on the highways and how to cope when it all kicks off

Sunday night was the big one on US TV. That’s when Ed Sullivan was on. Every night, between 8 and 9pm eastern time, American families would gather around their sets as the oddly stiff TV host introduced magicians, vaudeville acts, opera singers, and pop groups. Sixty years ago this month The Ed Sullivan Show changed Britain’s pop relationship with America forever. Over three consecutive weeks – on 9, 16 and 23 February – The Beatles performed, rewriting pop history with each appearance.

For the band’s first show, 73 million viewers tuned in – more than three times the usual audience for Sullivan; some 50,000 people had applied for the 728 spots available in the audience at Studio 50 in Manhattan. The Beatles offered an explosion of brash good cheer across five songs; a promise of something different and happier. Just like that, Beatlemania was launched, and with it “the British Invasion” as America turned to the new take on rock’n’roll coming out of England.

Since then, the idea of “breaking America” has been a great lure for British acts: all those would-be fans, that untapped potential and the open road. Few made it: most returned home with nothing more than an NME front cover of them in front of the Statue of Liberty. They all soon learnt that conquering the land of the free isn’t for the faint-hearted.

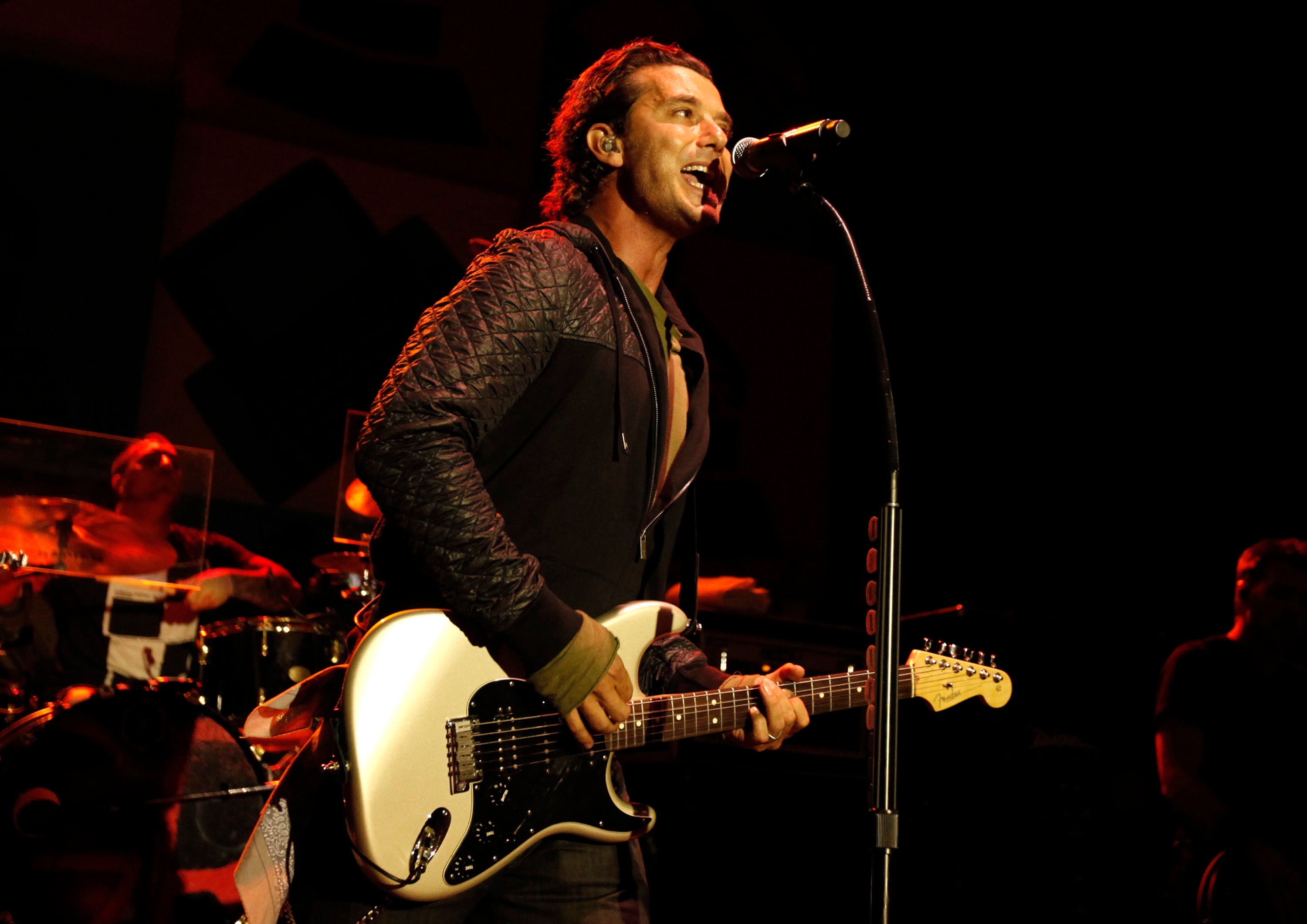

“There’s a great scene in the film Bronson,” says Gavin Rossdale, singer of Bush. “He says, ‘Most people go to prison and they can’t take it. I f***ing love it.’ And that’s the same mindset you need to make it in America.” It worked for him: Bush broke big in America with their debut album, Sixteen Stone, in 1994. Thirty years later, Rossdale still has a thriving career there. He even lives in LA.

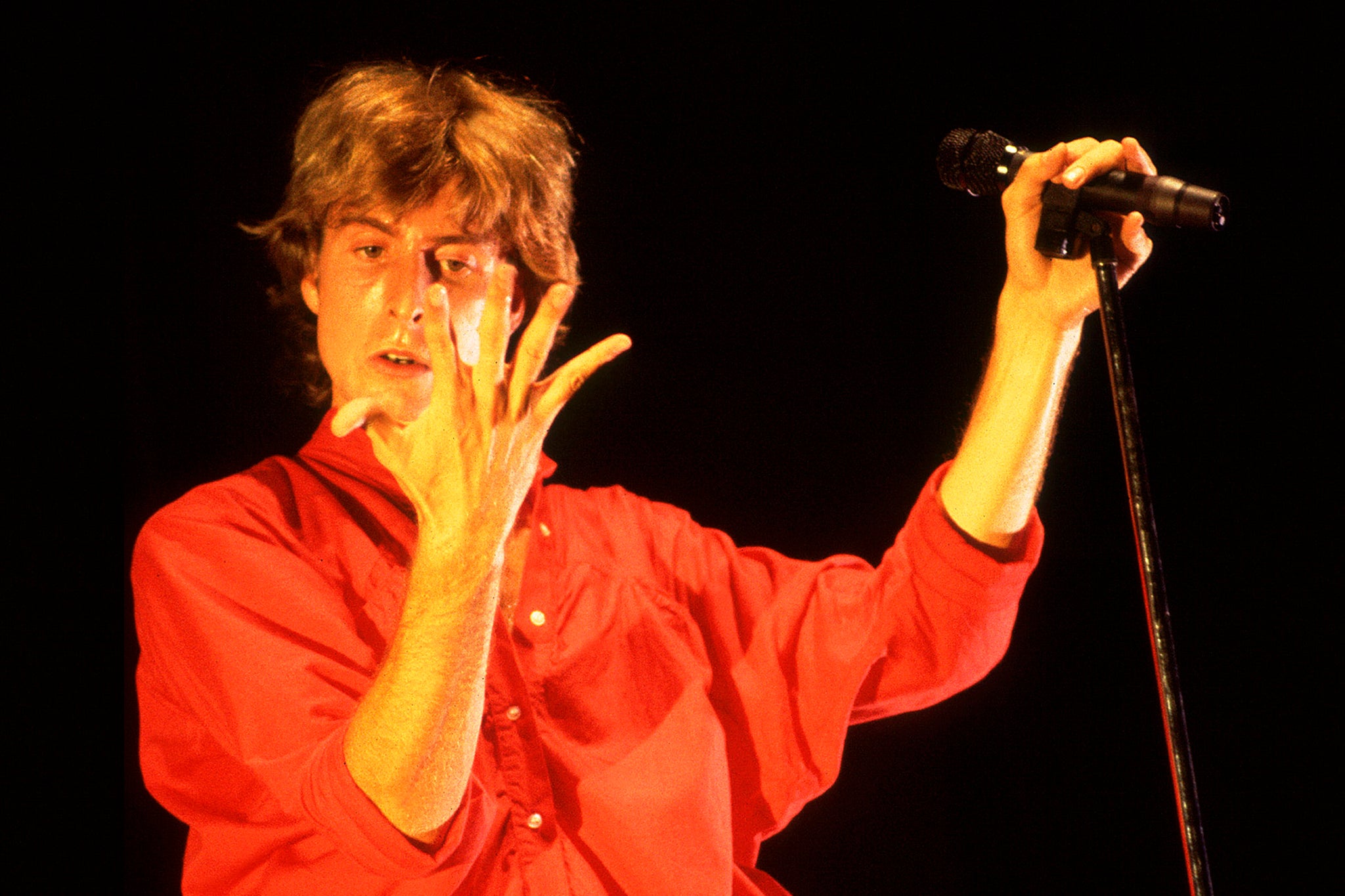

For some, no matter how gruelling, it seemed an awful lot less effort than returning home. “Having worked on a building site helped me,” says Dave Wakeling of The Beat and General Public. “Whatever I had to do, it was better than working.”

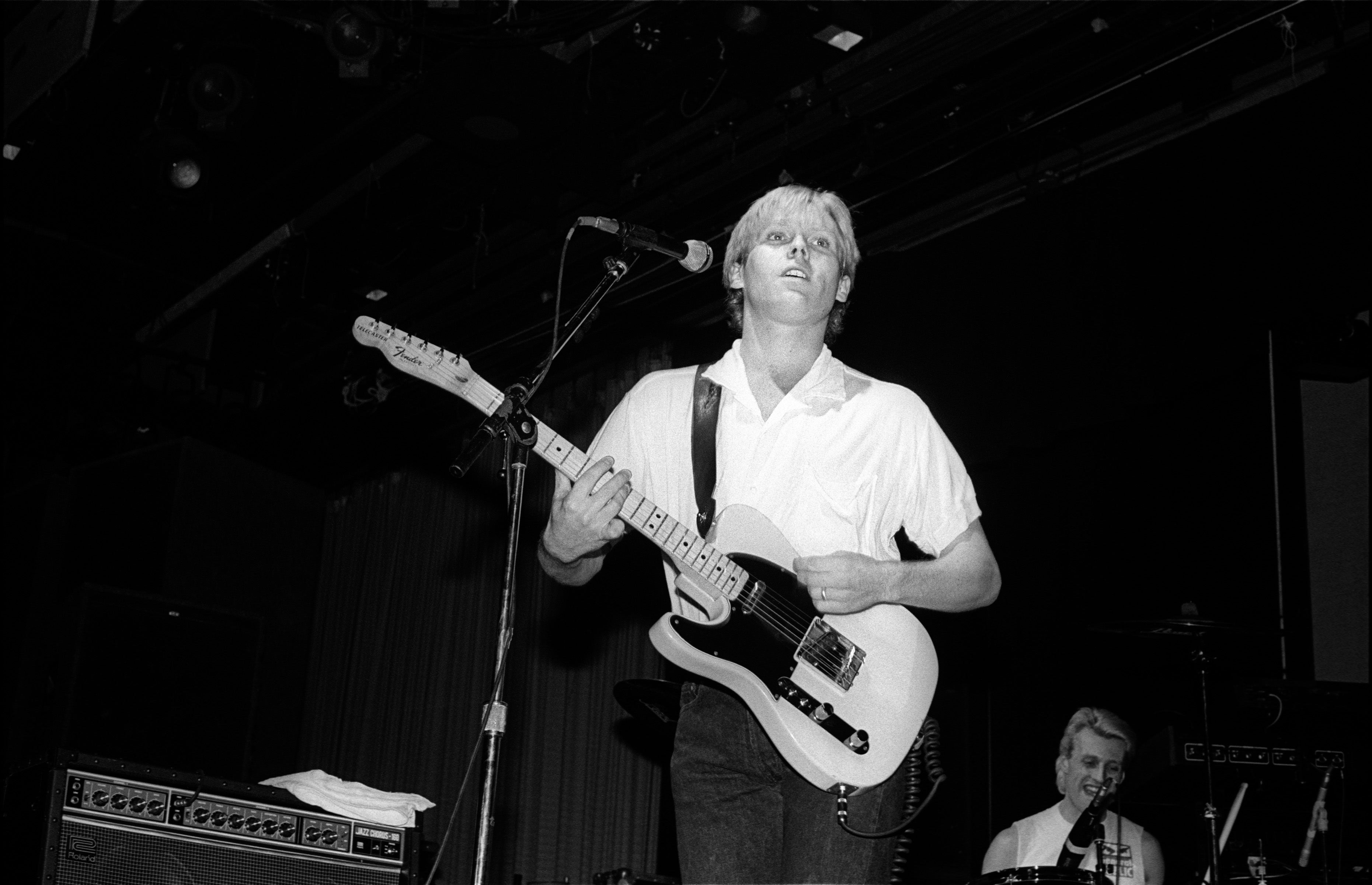

“It’s such a big market that you can stay on the road all year and never play the same place twice,” says Cy Curnin of The Fixx, who became a top 10 band in the US in the early Eighties without once breaking the top 50 at home. “It seems like it’s always fresh to the audience but you’re getting long in the tooth being on the road. We spent two years on the road permanently.”

Now, as then, the only real way to find success in America is to tour, tour some more, and then tour again. It’s all very well playing sold-out shows in New York, Chicago and LA – but to make it, you have to be willing to play everywhere: there are no flyover states for an aspiring star in America. It’s not a coincidence that The 1975 have become an arena-headlining act there. Matty Healy and co tour incessantly: their current cycle will have ended with 61 US shows, including such glamour destinations as Independence, Missouri; Grand Prairie, Texas; and Newport, Kentucky.

That model for Stateside success was set early, by the booking agent Frank Barsalona and artist manager Dee Anthony. Between them, the pair broke a score of British bands in the late Sixties and early Seventies – including Humble Pie, Jethro Tull, Peter Frampton, Joe Cocker and Emerson, Lake & Palmer – by sending them off on tour after tour, first as the opener, then as the headliner. After putting out three or four studio albums, they would have the bands record a live album that would tip their act over into superstardom.

Touring such a big country is exhausting, Wakeling says. “It would be an eight-week tour at minimum, And if it went well, after eight weeks you booked another month doing bigger venues in all the cities you’d done well in. It was often three months. While you’re doing it, you’re in such denial about how weird this whole thing is. It’s when you get home and stop and think, ‘Oh my God, what have you done?’” Playing to hundreds of fans every night, though, helped at least with the homesickness. “That always helps if you’re feeling lonely – you can jump off the bus and see what adoration is to be had,” Wakeling says.

Even in the Eighties, playing big support slots was important, Curnin says. “We hopped on The Police tour, playing to 1.5 million people in six weeks in stadiums, and public perception changed. The live experience is what sears you into the mind. Someone who comes to see The Police isn’t a Fixx fan but they can get caught up in the moment.”

I’m about to sell my house in France and the drummer called me up and said, ‘Clive, you don’t have to sell your house in France. LA’s gone crazy’

For The Fixx, it was a chance to sear themselves into minds. “You had 80,000 people screaming euphorically, so if you could give a good impression and back up what they’d heard on the radio then you could be seen as a solid act. We were able to show we had the goods.”

The first addition to the old model came in the Eighties, just in time for the second British invasion, with the launch of MTV. Suddenly, there was a national TV channel devoted solely to pop, and British bands were ahead of the game, having been making music videos already. “Radio was broken up into different styles and markets, so singles couldn’t hit at the same time across radio,” Curnin says. “Then along comes MTV and you are programmed across the nation. As cable companies provided it more and more, you could see the effect: each time you released a single, it would blow up. MTV was the first national music station where there was video and audio – and it was like an electronic babysitter. We still have fans turning up who saw all those videos.”

Def Leppard experienced the same thing, when their single “Bringin’ On the Heartbreak” went into heavy rotation on MTV in late 1981. It didn’t make the Billboard Hot 100, but it sent their album High ’n’ Dry platinum, months after release. “The great advantage was that nobody else had videos, so they were playing ours all the time,” singer Joe Elliott told me for my book Denim and Leather. “And then they were starting to get requests for them, so they were playing them even more.” Airtime on MTV translated into radio play, too, with viewers calling up the stations requesting the song they’d just heard on the telly.

America, then, was duly primed for their next record – the one that would make Leppard huge. “When we did release Pyromania and release these videos that were so much superior – “Rock of Ages”, “Foolin’” and specifically “Photograph” – it went f***ing nuts,” said Elliott.

That being said, MTV was not the be all and end all. Like TikTok now, MTV then could nab you a hit, but it couldn’t secure you a career. Today, US radio is still fragmented, but it remains a rite of passage for artists to preface a gig by visiting the local radio station and recording a series of jingles: “Hi, I’m so-and-so, and you’re listening to WFTK in Cincinnati!” Those cities, Rossdale says, “they love it if you go into their radio station. But it depends how much you want it.” For plenty of British acts, the endless grind of local radio stations proved too much; General Public, Wakeling says, tried to liven the routine up by slipping political messages into their appearances.

Actual airplay has always mattered, too – especially crucial stations in big markets, which would be a launchpad for the rest of the country. After Bush made their first record in 1994, Rossdale says, their distributor “said not only were there were no singles on the album, there were no album tracks”. They were dropped but it didn’t bother him. “I was so used to failure that I felt like just by making a record I had done something,” he says. “I was working next in a dentist’s office next to a branch of Miss Selfridge, and thinking, ‘You made a good record, so f*** ’em.’” For the next five months, there was nothing. “Then I got a call: ‘KROQ is playing your record!’ ‘What’s KROQ?’ It’s a big influential station in LA that’s the home of alternative music,” he says.

The album’s co-producer, Clive Langer – who was facing financial ruin because the studio he owned was losing money – was caught on the delighted hop by the album’s success. “I’m about to sell my house in France and the drummer called me up and said, ‘Clive, you don’t have to sell your house in France. LA’s gone crazy,’” he told me back in 2017. “And LA spread. And then it was in the shopping malls. It was Nirvana lite, but it sounded great. I got the biggest cheque I’ve ever had, and I paid off all my mortgages.”

But, Wakeling says, there might be reasons for a particular single blowing up on radio. The Beat had managed club hits after getting MTV airplay, but General Public, his next band, had proper Hot 100 hits. What changed? “General Public was the first time where radio stations had been financially taken care of,” he says. “I remember a dinner with some DJs in Boston, and I was told after that the record was going to be added to playlists, and it was going to go like wildfire after this – and it did. I believe a manila envelope changed hands.” Wakeling says he wasn’t offended by the implication his music wouldn’t win success on its own merits: “It was the name of the game. We were glad we’d finally joined the club.”

British bands would start to feel more entitled as they got deified [by British press]. They would have a sense of entitlement about being massive – and then they would come to the US and have to do the work and they couldn’t

There are, however, two things that really don’t work if you’re British and trying to break America. They first is being too British: it’s no coincidence that groups anchored in the minutiae of everyday life over here tend not to break out of their cult followings. The Jam and Madness might have spoken to the lives of British kids, but not so much to those of Butte, Montana. The second is turning up off the back of some British hits and assuming you’re already superstars, with an attitude to match.

Rossdale, never a press darling, notes how bands’ egos would get inflated by fawning coverage in the UK music weeklies like NME, Melody Maker and Sounds. In the US, they were in for a rude awakening. “They would start to feel more entitled as they got deified. They would have a sense of entitlement about being massive – and then they would come to the US and have to do the work and they couldn’t.”

A common theme among British musicians who truly succeeded in America is a slight regret that concentrating all their efforts over there meant they didn’t have the same impact at home. Elliott will still talk at length about how an article in Sounds magazine that accused Def Leppard of selling out to America in 1980 set them back several years in the UK. And Rossdale, for all his fame, still wishes things had been different here.

“I’ve never played empty shows and I’ve always played to people we connected to,” he says. “But I’m from London, so for me to have to leave my home to be successful was not ideal. I totally would have preferred to have something happen in England.” Rossdale pauses for a moment to think about the course of his career. “But I also have a lot and I shouldn’t be a twat about it: 26 million records sold, and lots of people just wish they had a record deal.”

Even now, as I write this, some young British band is touching down at JFK for the first time, wondering what their shot in the US will look like. Probably it’ll be a photograph in front of the Statue of Liberty – albeit posted on their Instagram rather than the front page of NME.

The Fixx play The Garage, London on 21 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments