How Britain’s ageing female stars rewrote the rules of the box office

Maggie Smith, Judi Dench and Helen Mirren have broken the mould for actors in their twilight years. With Smith having now passed, and Dench in retirement, Geoffrey Macnab looks at the history and uncertain future of the ‘old gold’ genre

Among the many glowing obituaries of Dame Maggie Smith, who died last week at the age of 89, one important point has mostly been overlooked. The great actor’s passing left a void in the hearts of many cinemagoers – but also, perhaps, in an entire subgenre of British cinema.

Along with her fellow dames Judi Dench and Helen Mirren, Smith had been raking in a queen’s ransom in international ticket sales over the last quarter of a century, much of which came from British-made films. If you look the trio up on box office data sites, you will find quite eye-watering figures next to their names, stretching into the billions.

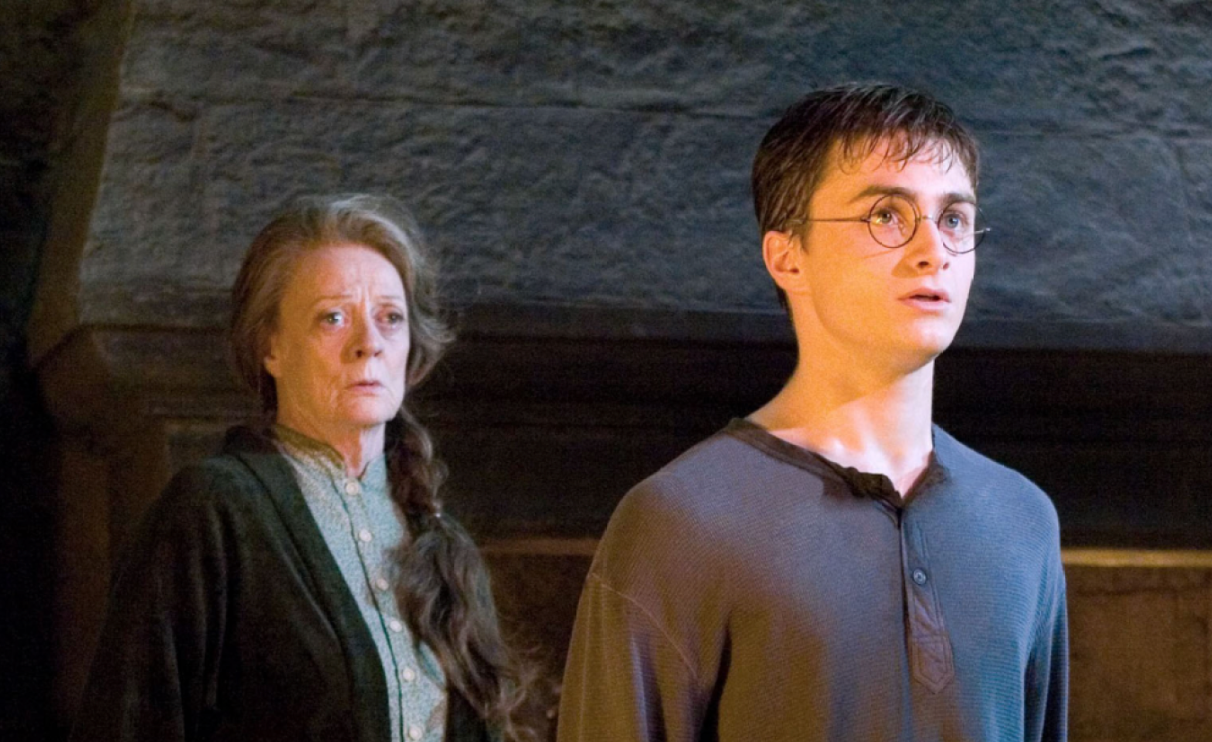

This is largely down to the three actors’ roles in big Hollywood franchises – Smith in Harry Potter, Dench in James Bond, and Mirren in Fast & Furious. But there also exists a rich, profitable, and all too often under-discussed ecosystem of films spotlighting these actors in their twilight years. With Smith’s death and Dench’s apparent retirement (she has a degenerative eye condition and turns 90 in December), the British film industry is facing the loss of two of its most bankable and irreplaceable stars.

Any cultural history of UK cinema from the 1990s to the present day will surely have to acknowledge Mirren, Dench and Smith as among its most important figures. They’ve won multiple awards. Their films have been far more widely seen internationally than those of most of their male contemporaries. They’ve shown astonishing versatility and drive, too, sustaining top-level screen careers at an age when most other actors of their vintage have long since stopped working. They’ve played monarchs, empresses and haughty aristocrats – but they’ve also taken on roles as police detectives, mother superiors, lonely spinsters, housekeepers, housewives, nurses, novelists and teachers.

Ironically, none of them, at the start of their working lives, were much interested in movies – and movie producers weren’t always keen on them, either. They’ve had by far their biggest hits in the latter part of their careers – and the story of how these dames became box-office titans is a surprising and random one.

“Miss Dench, you have every single thing wrong with your face,” Dench was famously told by a film producer after her first screen test in the 1950s.

“It put me off films for a long time, and my few early excursions into the cinema did little to change my mind,” the star later wrote. Dench, born in December 1934, freely acknowledges she has always been far more interested in stage than screen. She made her screen debut in 1964 in Charles Crichton’s black and white B-movie The Third Secret, but it was only in the 1980s that her movie career really cranked into gear with her roles in films such as A Handful of Dust (1988), A Room with a View (1985), and Wetherby (1985).

A decade later, in her sixties, Dench began to land her most eye-catching roles, as MI6 boss “M” in the James Bond films, Queen Victoria opposite Billy Connolly’s hairy Scottish gamekeeper in Mrs Brown (1997), and as a commanding but subtly vulnerable Queen Elizabeth I in 1998’s Shakespeare in Love (“I know something of a woman in a man’s profession”). During the latter film, she was only on screen for eight minutes and yet still won an academy award for Best Supporting Actress.

Smith’s venture into cinema was almost equally erratic. Like Dench, she was attacked early on because of her unusual looks. “Oh, you can’t let her, not with that face,” her grandmother supposedly remarked to her mother when young Maggie first expressed a desire to act professionally.

Her movie career initially seemed haphazard in the extreme. She won her first Oscar for playing the romantic-minded but deluded and fascist-leaning Edinburgh school teacher in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1969), and picked up another one for her comic cameo in the Neil Simon adaptation California Suite (1978), but often seemed to choose her parts on a whim.

As critic David Thomson wrote, Smith’s movie career was “blithely indifferent to reason or line ... [She did] a little bit of everything.” She’d be in a Merchant Ivory costume pic one moment and then in a half-baked fantasy like Clash of the Titans (1981) the next. It wasn’t clear if she was a character actor or a star, or a bit of both. She excelled in mannered comic roles, but was even better when playing lonely and damaged characters. Smith’s most famous projects, from Jean Brodie early in her career to The Lady in the Van late on, combined comedy with a harrowing pathos.

Mirren, meanwhile, started off on stage, and still admits today to the nagging feeling (one she describes as “quite wrong”) that movies somehow aren’t quite “real acting”.

If you are in a play, she told Alan Alda’s Clear & Vivid podcast in 2021, “you’re your own editor ... you have final cut [over your performance]”. In her early movies, she felt she was “utterly useless”, with no idea about camera, framing or rehearsals. “When I started off in film acting, I called it ‘deer in the headlights’ acting ... I felt shy and embarrassed in a film set,” she said.

Mirren was in some striking movies in the 1970s and early 1980s – among them the recently re-edited Roman sex, sword and sandal romp Caligula (1979), gritty red light drama Hussy (1980), John Boorman’s Arthurian epic Excalibur (1981), and dark love story Cal (1984), set in Ireland during the Troubles. She credits her role as Detective Chief Inspector Jane Tennison in TV’s Prime Suspect, fighting both crime and institutional sexism, with shifting attitudes towards her.

It’s 20 years now since Dench and Smith co-starred in actor Charles Dance’s directorial debut Ladies in Lavender (2004). This was a 1930s-set costume drama about two Cornish sisters who find a handsome but near-dead Polish castaway on the beach. As they nurse him back to health, he stirs up unholy passions. Made on a relatively modest scale, the film was full of familiar tropes from British heritage cinema – beautiful costumes and landscapes, and jokes about sex, class and nationality. It was nonetheless a groundbreaking affair.

“It’s about emotions and feelings that mainstream cinema will have us believe are really only experienced by 15- to 21-year-olds,” said Dance. “In this case, it is about two ladies in their sixties, in the autumn of their life.” Dench and Smith weren’t the elderly eccentrics, making cameo appearances. They were the story’s main protagonists, both full of longings and doubts. Foreign distributors were enchanted by Ladies in Lavender, which sold all around the world.

Dench and Smith had known each other since the late 1950s. Long before Ladies in Lavender, they enjoyed considerable success together in films like A Room with a View and Franco Zeffirelli’s comedy-drama Tea with Mussolini (1999). After Mrs Brown and Shakespeare in Love, Dench had won further plaudits for playing Iris Murdoch suffering from Alzheimer’s in Iris (2001), while Smith and Mirren had both been Oscar-nominated for Gosford Park (2001).

However, Ladies in Lavender convinced financiers that the dames could carry even relatively low-budget indie films on their own. They were no longer regarded as contemporary equivalents to Edith Evans, Sybil Thorndike or Margaret Rutherford a generation before, the stern matriarchs and dotty aunt types to be wheeled in primarily for comic relief. They were now playing leading roles in box-office hits such as The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2011) and its sequel The Second Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2015).

Movies may have started as an afterthought for all of them, but that has completely changed over the last 30 years. All three of the dames went on to appear in big mainstream pictures, adding to their cross-generational appeal and attracting new fans who didn’t even realise they were giants of the British stage. Dench featured in eight James Bond films. Smith played Professor Minerva McGonagall in the Harry Potter saga, and starred in the Downton Abbey TV series and follow-up films. Mirren, meanwhile, co-starred as “Queenie” Shaw in the Fast & Furious movies, and took the leap into superhero movies as Hespera, the ancient goddess with a grudge against humanity, in DC’s Shazam! Fury of the Gods (2023).

In the Summer of 2020, Dench was a Vogue magazine cover girl when she was 85 – a sign of her continuing cultural relevance. “Dench is still squarely present on the Hollywood A-list, one of a tiny elite who can get a movie green-lit,” the magazine gushed in regard to the still imperious actor. “They are much-prized talents on the international stage,” Ladies in Lavender producer Elizabeth Karlsen agrees. But Mirren, 79, is the only one still working regularly on screen today.

The vast outpouring of affection toward Smith since her death last week will quickly be followed by mounting apprehension among UK film financiers. The era of the box office’s golden dames may be coming to an end. Whether or not a younger generation of elderly actors will rise up to replace them remains to be seen.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks