Why has Hollywood turned its back on the American everyman?

Salt-of-the-earth heroes have long been a staple of American cinema, from ‘12 Angry Men’ and ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ to ‘Erin Brockovich’. Geoffrey Macnab laments the decline of one of cinema’s richest storytelling traditions

It’s one of the great scenes in one of the classic movies of its era. Henry Fonda, as the migrant sharecropper Tom Joad at the end of the John Steinbeck adaptation The Grapes of Wrath (1940), stands with a fervent, messianic expression on his face, railing against the injustice he sees all around him. Joad vows to take the cause of the ordinary Joe. “I’ll be all around in the dark,” he says. “I’ll be everywhere, wherever you can look. Wherever there’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever there’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there. I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad.”

It’s an electric moment, one that inspired Bruce Springsteen’s coruscating 1995 song, “The Ghost of Tom Joad”. And it remains one of the most famous sequences in Fonda’s entire career. Joad is a type who used to be found all the time in American films – but has now seemingly been wiped out of existence. He’s the hero from a humble and often troubled background who has integrity, defiance and the courage to speak out against injustice. Sally Field (in 1979’s Norma Rae) and Julia Roberts (in 2000’s Erin Brockovich) won Oscars for playing characters with precisely these traits. Fonda and James Stewart became household names for their many portrayals of salt-of-the-earth American everyman heroes taking on powerful vested interests – Stewart particularly in his Frank Capra collaborations It’s a Wonderful Life and Mr Smith Goes to Washington. Audiences cherished their performances. But you won’t find their equivalents in US films today.

Blame the reluctance of older audiences to return to cinemas post-pandemic. Blame the algorithm-based tracking systems that have convinced the US studios that dramas in general, let alone ones with a social conscience, are toxic at the box office. Blame the wariness among mainstream filmmakers about broaching political subject matter. Blame the blinkered and cowardly commissioning policies of the studio executives. Whatever the reasons, the types of films that catapulted Fonda and Stewart (among others) to stardom are simply no longer being made – and cinema is all the poorer as a result.

In the brave new world carved out by contemporary Hollywood, there are huge-budget Marvel and DC movies at one end of the scale and edgy, low-budget genre fare at the other – with a void in between where the films like Norma Rae and Erin Brockovich used to sit. Today, the dominant narrative is not that of the everyman, but the superhuman: being a hero requires not just pluck and derring-do, but also the ability to shoot lasers out your eyes, or webs from your wrist.

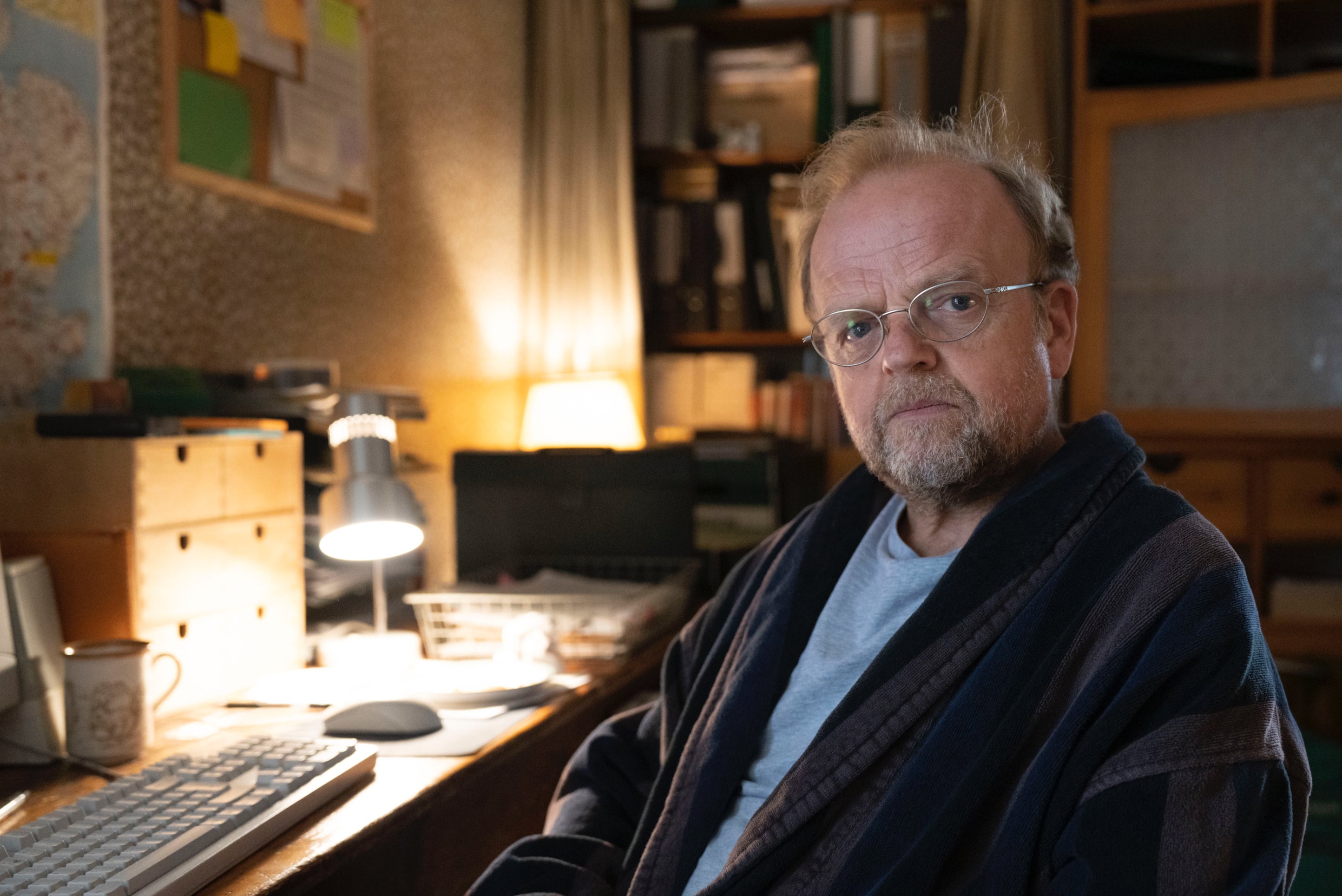

In the UK, a reported 13.5 million people watched ITV’s Mr Bates vs The Post Office earlier this year. The series dramatised the shocking story of the Post Office workers wrongly accused of stealing cash from their branches. In fact, the Post Office’s own faulty computer system was to blame for the missing money. The drama provoked a national outcry and its main character, the subpostmaster Alan Bates (Toby Jones) fighting stubbornly for justice against uncaring bosses, bureaucrats and politicians, became a modern-day Best of British national hero.

The popularity of Mr Bates suggests there is still a hunger among audiences for stories about the common person fighting back against corruption, incompetence and injustice. The US studios, though, seem to have forgotten all about the power of the underdog.

That’s why you’ll no longer find any new big-screen moments like the one in Martin Ritt’s Norma Rae when Sally Field’s character is fired. She is ordered to leave the textile factory immediately. She refuses to quit, stands on a table, scrawls “union” with some charcoal on a piece of cardboard, and holds the sign up for all the other workers to see. Eventually, their machines fall silent. This tiny woman on a factory floor surrounded by bulky, bullying men, has somehow started her own mini-revolution.

“Norma Rae is depicted as a champion of labour, a defender of civil rights, and an icon of feminist liberation,” wrote academic Angela Allan, who accused the film of “basking in the individual bravery” of a white woman who could single-handedly “bring the grinding machine of corporate capitalism to a halt”. In a way, it was all a little absurd. Nonetheless, not many other movies about would-be union organisers in racist southern cotton mills have won Oscars.

Other older movies have a similar contemporary resonance when they are revived today. Sidney Lumet’s 1957 classic 12 Angry Men, which screens at BFI Southbank this week, may be stagy and melodramatic in its construction but feels very modern in the way it exposes racial and generational tensions. Henry Fonda is juror number eight, holding out against his 11 colleagues who are already convinced of the guilt of the Puerto Rican youth on trial for murder. In today’s America, there are still plenty of cases of teenagers involved in alleged gang crimes being sent to prison on flimsy evidence by juries not willing to cut them any slack.

In 12 Angry Men, Fonda wins over the audience as well as his fellow jurors by dint of his sheer decency and common sense. Despite its formal constraints, the film (based on a TV play by Reginald Rose and set in a single room) makes riveting drama.

There used to be many other movies about people in seemingly dead-end jobs or terrible circumstances who showed transcendent heroism. In Mike Nichols’ Oscar-nominated Silkwood (1983), Meryl Streep plays a worker and union activist at a nuclear fuel production centre who reports her concerns about the radiation poisoning going on unchecked at the facility – and dies in suspicious circumstances.

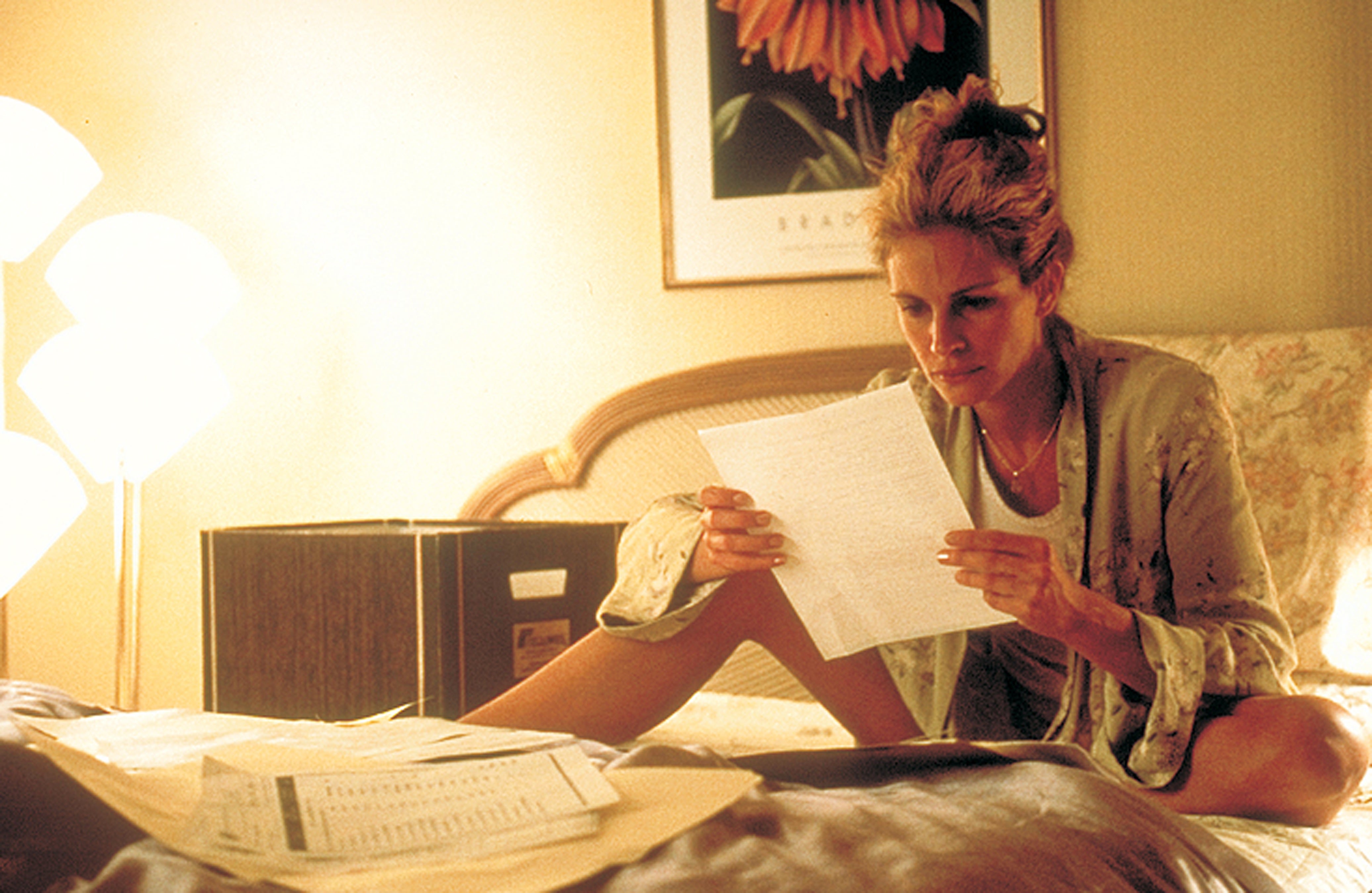

In Steven Soderbergh’s Erin Brockovich (2000), the cash-strapped, twice-divorced, blue-collar single mother turned legal assistant (Julia Roberts) takes on the company whose reckless policies have caused multiple cases of cancer. “You not only witness the humiliations casually and routinely visited on working-class women; you feel in the pit of your stomach the overwhelming anxiety of impoverished single motherhood, which often amounts to a state of sheer terror,” The New York Times wrote of another Oscar-winning film that simply wouldn’t have been made today.

Sadly, stories about characters like Karen Silkwood, Norma Rae and Erin Brockovich are no longer being told - and no one in Hollywood is trying to make dramas about migrant farmers like Tom Joad either.

Careers are suffering as a result and the awards race is becoming markedly less interesting in the process. The Oscars and Golden Globes now routinely go to actors who give the most showy and unusual performances. A strong argument can be made, though, that it is far more challenging to play “ordinary” heroes than to showboat in extravagant costume dramas or to portray larger-than-life personalities caught in extreme situations.

George Clooney is a prime example of someone struggling in a Hollywood ecosystem that doesn’t allow him to take on the type of projects that Stewart and Fonda used to make so regularly. Clooney had by far his greatest hour as a filmmaker telling the story of broadcaster and journalist Edward R Murrow (David Strathairn) in Good Night, and Good Luck (2005). This was a sober but very powerful black-and-white drama set during the McCarthy-era anti-communist witch hunts. At great personal risk, Murrow spoke out on air against the red-baiting senator and helped bring him down by doing so. Clooney himself played a supporting role as Murrow’s producer, Fred Friendly. The film had an urgency and impact you certainly don’t find in the actor’s more vacuous star vehicles like Wolfs, his recent action comedy with Brad Pitt. In our era of fake news and culture wars, Good Night, and Good Luck feels as topical and relevant as ever – but it wouldn’t be made today.

Audiences (we are continually told) don’t want stories that preach at them. “Pictures are entertainment. If you have a message, call Western Union,” runs the famous quote most commonly attributed to producer Sam Goldwyn. Nonetheless, in dispensing with dramas about ordinary characters showing courage and integrity in extraordinary circumstances, Hollywood has cut off the source of some of its very greatest works. It’s a sign of defeatist pessimism about what cinema can actually achieve. After all, if you’re not trying to change hearts and minds, what’s the point of making movies in the first place?

‘12 Angry Men’ screens BFI Southbank, 29 Sept

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments