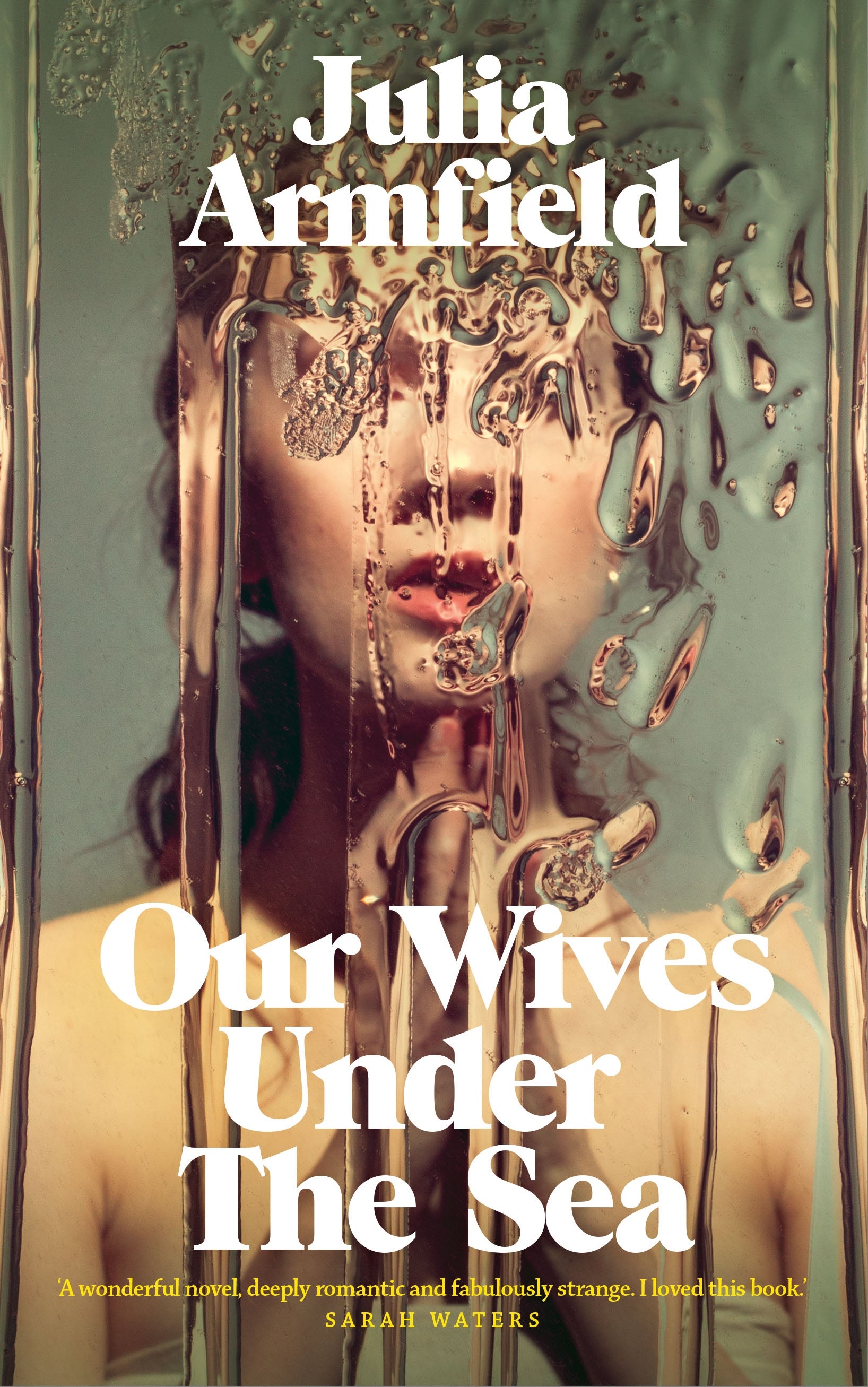

Our Wives Under the Sea author Julia Armfield: ‘Horror and romance spring from the same core’

The award-winning writer of ‘salt slow’ blends genre fiction to dazzling effect in her debut novel. Kate Wyver talks to her about ‘reckoning with the body’, the ocean depths and the myth of success

Julia Armfield has an unconventional attitude to romance. “Horror is the most romantic genre,” the author says when we speak over Zoom, a few days before Valentine’s Day. She tilts her head, as if it’s obvious. “In some ways, I think the two things are synonymous.”

The 31-year-old Londoner has just published her debut novel, Our Wives Under the Sea. Her first book, 2019’s salt slow, is an eerie, sexy collection of short stories that injects the mythic and monstrous into mundanity, with unsettling flashes of winged women and stone lovers. One of its stories, “The Great Awake”, in which sleep steps out of peoples’ bodies and wanders around at night, won the 2018 White Review short story prize. In Our Wives Under the Sea, Armfield continues her unique conjuring of the uncanny, as we follow Miri and her wife Leah – who works in deep-sea research – into the sinking abyss.

Armfield is sitting at her kitchen table, the countertop messy behind her. She leans on her elbows and speaks quickly. “Horror centres around a lot of the same things that I think work in romance,” she says. “They both spring from the same core, touching on quite primal feelings and fears. Both centre around extremity, passion, and trauma.” When Leah returns from a mysteriously delayed submarine trip, somehow not herself, Armfield combines the looming fear of the unknown with the terror of losing the person you know best.

It’s no wonder gothic influences seep into Armfield’s stories; she did a masters in Victorian Art and Literature at Royal Holloway, focusing her thesis on teeth, hair and nails in the Victorian imagination. Growing up in Surrey, she’d always written in her spare time, and had her writing published in a variety of literary magazines before she got close to releasing a book. She found an agent when a collection of her short stories was longlisted for the Deborah Rogers Foundation Prize, and soon afterwards won the White Review prize.

Daily life is slightly askew in the world of Armfield’s writing. In spite of something deeply sinister joining Miri and Leah in their flat, the writer creates an unshakeable sense of normality, with strange new events quickly settling into part of the couple’s routine. They watch movies. They get the bus. Then just as casually, they clear up the pools of water that Leah has vomited up for the fifth time that night. “I like doing genre in an extremely realist setting,” Armfield says. “I’m fascinated by the way people don’t react to shocking things by continuing to be shocked. People accept things very quickly.” She compares it to the past two years, and the way we all just got used to the onslaught of daily terror and bad news. “People do not just go on being horrified.”

The way Armfield writes about the body is incredibly tactile. You can feel the softness of ankles hooked over each other, the weight of limbs intertwined. This focus on flesh will be familiar to readers of salt slow. In the short stories, body parts are scattered throughout: cut off, buried, attached in places they shouldn’t be. In Our Wives Under the Sea, this acute attention to the body and what it feels like to be inside it is taken even further, with breadcrumb trails of flaking skin and pinprick pores leaking blood in the night. Some scenes are grotesque, almost filmic in the way they’re described.

“I’ve always been really compelled by body horror,” Armfield says cheerfully. “I’m interested in the fact of pain being in some sense inescapable and inevitable. That happens to all of us, whether it will happen gorily and aggressively, or whether it’s just an inevitable deterioration of the body.” She adjusts her glasses and rests her chin on her hand. “One must always, at some point in one’s life, reckon with oneself as a body.”

She repeatedly references the influence of horror films. She finds them comforting. “I always feel really dumb whenever I’m doing an interview or a panel, and all these really intelligent writers are talking about all these wonderful books they were inspired by,” she says, “and then I’m like, ‘I watched the movie Suspiria.’ I obviously read a lot” – she rifles through some stacks of books and papers on the table to grab her copy of Parallel Hells by Leon Craig, which she just finished, and Devil House by John Darnielle, which she’s currently halfway through – “but I’m much more inspired by film.” This extends to the way she first imagines her stories. “It usually starts with a scene, or something that I can see filmically, and I build out the scaffolding from there.” The origin of Our Wives Under the Sea, which she initially wrote as a short story, was the image of somebody deteriorating into a bath.

Much of the fear in the book stems from water. While the sinking dread rests with Miri at home, the actual danger lives deep down in the ocean, with Leah’s research work. As we travel through the book, section headings outline the layers of the ocean, from the sunlight zone just beneath the surface, all the way down to the oceanic trenches of the hadal zone. Taking its name from the Greek god of the underworld, this is the deepest part of the ocean. 11,000 metres below sea level, it accounts for some of the least explored ecosystems in the world. Everything down there is either terrifying or unknown. Armfield describes the way the book’s narrative works as one thing going up, and the other going down. “It’s the romance,” she says, her right hand going from bottom to top, “and the horror,” her left going from top to bottom. Her hands pass in the middle, around the hostile environment of the midnight zone, where sunlight has long since ceased to reach.

It’s these unexplored depths that draws Armfield to writing about water. “The deep sea might be dark,” Leah tells us in the book, “but that doesn’t make it uninhabited.” “I’m fascinated by the dominance of a place we really don’t understand,” Armfield explains. “It’s not dissimilar to the way people feel about space. It emphasises the complete incidentalness of us.” Returning to the idea of the body and the way it can wither, she considers the idea of people being “in some way porous, in some way affected by their surroundings”. If someone spends too much time in extreme pressures under the sea, she asks throughout the book, what impact could that have on their physical being?

Armfield wrote salt slow around a full-time job. When I ask if she can write full-time now, she laughs. “There is a myth that writing is a rarefied occupation,” she says, “that as soon as you reach a certain stage, you’re able to do it in a meadow with a buttercup in your hair.” She still works full-time, doing legal education at the Inner Temple, one of the inns of court, in central London. “It is something that the majority of writers I know do when they can, around other things. The myth of success in writing is real.” She describes the desire to write as a kind of compulsion, almost a nuisance. “It is something that has just unfortunately been the case for me,” she says, “that at some point, I will just need to write something.”

Most of the stories Armfield writes that involve relationships are gay or bisexual. In Our Wives Under the Sea, she gives the women’s queerness space to lounge – to love, to bicker, to rest. “As women, it’s always like everything you write is biographical, but I am a gay woman in a relationship with a woman, so it was what it would have occurred to me to write.” There are delicate snippets of their life as a queer couple that have nothing to do with their encounter with something terrible under the sea. Several early readers have told Armfield that the couple feel universal. “They say it’s romantic,” she says, “because it feels like it could have been any two people in love. I’m like, fair enough,” she smiles, “but they are lesbians. There is specificity to that. There is specificity to living in the world as two women who are in love in a public sense and in a domestic sense. It was very important to me to have a specifically queer couple at the centre of things.”

In the glimpses of Miri and Leah’s life before the submarine expedition, we see them at parties and in bars. We notice how strangers fumble when they realise these two women are together. In details like these, Armfield roots the characters in our world. “It was important to me to reflect reality while at the same time writing a very fantastical book.” She says she was recently reminded of just how unused to seeing queerness people can be when she had an inpatient stay in hospital, and her girlfriend was with her. “Six separate people in the hospital assumed she was my mother,” she laughs, clearly still baffled by the experience. “She’s younger than me! Everyone was like, ‘Oh, is it Mum?’ And then they’d overcorrect, and be like, ‘Big sister? Housemate? Milkman?’ I know that happens, and it’s happened to me before, but it was just so many in a concerted place.” She shakes her head. “If I’d written this, somebody would have edited it out for being too on the nose.”

Julia Armfield’s debut novel ‘Our Wives Under The Sea’ is out on Thursday (Picador, £16.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments