Books of the month: From Brown Girls to The Colony

In his monthly column, Martin Chilton reviews six of the best books from February

Joseph Stalin would have made a pungent book critic. The Soviet leader, who claimed “journalist” as one of his “special skills”, included his verdicts in the margins of many of the 25,000 books and manuscripts held in his private library. In Stalin’s Library: A Dictator and his Books (Yale University Press), author Geoffrey Roberts includes some of Stalin’s choicest insults about books and writers, including “gibberish”, “haha”, “nonsense”, “fool” and “scumbag”. Alas, we are not told which book prompted him to write the simple critique “piss off”.

When Stalin liked something, incidentally, he wrote “spot on” or “yes-yes” – terms that could apply to several novels coming out this month, including Joel Agee’s The Stone World (Melville), a gentle, graceful novel in which the son of acclaimed writer James Agee tells a fictionalised version of his childhood in Mexico. I also enjoyed Ayanna Lloyd Banwo’s When We Were Birds (Hamish Hamilton), a spooky love story set in modern Trinidad, and Samuel Fisher’s unsettling fable-like Wivenhoe (Corsair), set in an Essex village, in an alternate present where the world is blanketed by snow.

For a time in the 1960s, Merle Haggard was the biggest-selling country music star in the world. In The Hag: The Life, Times, and Music of Merle Haggard (Hachette Books), Marc Eliot looks at the controversial life of the man who wrote classics such as “Workin’ Man Blues” and “Okie From Muskogee”. Haggard was a bizarre man, evident in his creepy behaviour towards Dolly Parton and his aggression towards touring partner Bob Dylan. The book also contains a graphic account of Haggard’s three years as a prisoner at San Quentin jail, where he was sent in 1958, aged just 20. He witnessed horrendous racism, including a black inmate being boiled alive. Perhaps it’s no surprise that he went on to write gritty songs.

Heavy metal fans will find much to enjoy in Michael Hann’s Denim and Leather: The Rise and Fall of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (Constable), in which the former music editor of The Guardian pulls together sharp, funny tales from many of the leading participants in a fevered time of change in heavy rock.

Perhaps the most disturbing book of the month is Darren Byler’s In the Camps: Life in China’s High-Tech Penal Colony (Atlantic Books), in which the professor of International Studies at the Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, investigates the allegations of the Orwellian-like control used by China’s rulers to oppress more than a million-and-a-half Uyghur Muslims in its vast north-western region.

Some 70 per cent of the earth’s surface lies under water. Chris Armstrong’s A Blue New Deal: Why We Need a New Politics for the Ocean (Yale University Press) is an important look at the climate and industrial devastation hitting oceans. I winced reading the chapter “Protecting Workers at Sea”, which lays bare the horrific abuse of fishing workers in Asia. “For the most part, the exploitation and abuse of workers at sea takes place out of sight and out of mind,” remarks Armstrong, a professor of political theory at the University of Southampton.

Once asked by a young fan if he could kiss the hand that wrote Ulysses, James Joyce replied, “No, it did lots of other things too.” This February marks 100 years since the publication of Joyce’s novel about the events of a single day in Dublin. Reading Ulysses is like scaling a literary mountain and if you’re up for the challenge then Penguin Classics has published a lovely new clothbound edition to mark the centenary.

Novels by Monica Ali, Daphne Palasi Andreades, Lan Samantha Chang, Audrey Magee and Vesna Goldsworthy, along with a non-fiction book by Professor Guy Leschziner are reviewed in full below.

Love Marriage by Monica Ali ★★★★☆

Love Marriage, set in London in 2016-2017, is about two very different families, both emotionally hobbled by long-held secrets, lies and betrayals. The Ghorami and Sangster clans become inextricably linked when Yasmin Ghorami and Joe Sangster, both young doctors, fall in love and become engaged. Both families are very different, but they are alike in their capacity for deceiving each other and deceiving themselves.

Ali, who was born in Bangladesh and whose family moved to England in 1970 when she was three, explored her past in the brilliant Brick Lane, which came out 16 years ago. Love Marriage also deals with the immigrant experience of England, through Shaokat and Anisah (Ma and Baba) and their children Yasmin and Arif. Sometimes this is shown through the sardonic lens of their relationship with their future in-law, Joe’s mother Harriet, an identikit Islington feminist author and broadcaster. At the start of the book, Joe jokes that Harriet will love the fact that he is marrying a woman of Indian descent, adding “your parents are authentic enough to give her an orgasm”. The way Harriet gradually takes ownership of Anisah, treating her like a pet, is deftly presented.

Although the novel, 500 pages long and written in short, sharp chapters, deals with serious subjects, including racism, religion, Islamophobia, addiction, therapy, sex, sexual politics and social media, there is an appealing lightness of touch to Ali’s writing. One small example of her wit and social comedy: Baba drives a Fiat Multipla, and if you don’t know what that looks like, I would suggest searching for an image so you can fully appreciate Ali’s description of the car as “the bug-eyed, bulge-headed Elephant Man of motoring”.

Yasmin’s work in geriatric care allows Ali to present a scorching view of life within the NHS, from the internal politics to the pompousness of male consultants. Anyone who has watched a medic trying to get a blood sample from a pensioner will also appreciate Ali’s simile that “drawing blood from a vein was like trying to light a candle without a wick”. It is also hard to forget Yasmin’s patient, Mr Sarpong, a man with a hydrocele in his scrotum “the size of a helium balloon”.

As the wedding day draws closer, emotions within both families begin spiralling out of control as secrets spill into the open. Love Marriage draws you into caring about the main characters and makes you ponder on the assumptions we carry around about the people closest to us. Ali has written a brilliantly tender and compelling novel about who we are and how we love in 21st-century Britain.

Love Marriage by Monica Ali is published by Virago on 3 February, £18.99

Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades ★★★★☆

Daphne Palasi Andreades’ debut novel Brown Girls, which started out as a short story, follows a group of young women who are first- and second-generation immigrant daughters, as they come of age in “the dregs of Queens”, the New York district where the author was born and raised.

This strikingly exuberant novel is told in the first-person plural – the “we” represents a chorus of voices of girls and young women belonging to different diasporas – and the refrain “brown girls brown girls brown girls” is repeated frequently. “Brown” means “unease”, Andreades says. Her novel examines the racism and everyday humiliations these young women face (there is a devastating anecdote about one girl being asked to stand at the edge of a group being photographed, “in case I need to cut you out later”).

Although the book is slim – told in short chapters over 203 pages – the scope is ambitious: it deals with gentrification, the class system in America, the experience of colonisation and migration and surviving in a land ruled by a “poisonous” president. The novel is also full of wonderful little observations about the sights, sounds, smells and tastes of growing up in Queens.

The book certainly has spiky, thought-provoking things to say about an immigrant community living on the margins of American life, but it is most memorable in its gorgeous depictions of friendship. It is also an incredibly moving meditation on growing up and how time and distance give perspective – especially in the way we sometimes gradually understand what our own parents went through in the arc of their lives.

This gives a novel set in Queens a powerful universality. “How did we become this way? When did we stop being the people we needed for each other?”, one character muses. As, indeed, we all do.

Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades is published by 4th Estate on 3 February, £12.99

The Family Chao by Lan Samantha Chang ★★★★☆

Leo “Big” Chao is the cruel patriarch whose suspicious death is the mystery at the heart of Lan Samantha Chan’s inventive literary thriller The Family Chao.

Drawing inspiration from Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, in which three brothers struggle against a tyrannical father, Chang has written a clever comedy about the immigrant experience, one that takes neat pot-shots at the American Dream. Leo, who with his wife Winnie has built a successful Chinese restaurant, is described by one of his sons as the consummate American, “an insatiable narcissist, a shameless capitalist who wanted to screw everyone”.

The novel, based around Leo’s three sons – the reckless eldest son Dagou, the smart lawyer Ming and the naïve college student James – is set in Haven, Wisconsin, described variously as “wretched”, “lousy” and a “godforsaken heartland of deprivation”. Chang, director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, is the child of immigrants who left China in 1949, and she draws on her own background and the perspective of an outsider to astutely explore the contradictory views and desires of Chinese Americans and their stories.

There are sub-plots and twists – including around O-Lan, a recent immigrant from Guangzhou whom nobody seems to know much about and whom the family dislike for her “fox smell and shovel jaw” – and plenty of lines to make you smile, including about a marriage that is thwarted to prevent a woman from ending up as Winnie Pu.

Chang, who creates wonderful evocations of the smells and tastes of restaurant life, explores anti-Asian racism through the notes of a journalism student called Lynn Chin, who is blogging about the trial of a man dubbed in the press William Dagou “Dog Eater” Chou.

Chang’s entertaining portrait of a “clusterf**k” Chinese-American family, one riven by its own jealousies and secrets, is also a memorable expose of the dark undercurrents of small-town morality.

The Family Chao by Lan Samantha Chang is published by One on 3 February, £16.99

The Colony by Audrey Magee ★★★☆☆

The Colony, the second novel from the Women’s Prize-nominated Audrey Magee, is on the surface the story of two men – an English painter and a Frenchman who is a language specialist – who arrive to document a small island off the west coast of Ireland. Truth and reality become blurred as they attempt to investigate what constitutes identity.

The lyrical verbal exchanges around the visitors are intersected with brutal and sparse descriptions of the violence being wreaked in the summer of 1979 in Ireland itself. As one character movingly puts it: “The violence and chaos of those deaths, of that bloodshed, living alongside the beauty of the people, of the landscape, a disrupted, upended Garden of Eden, a suspended state, a state of unfinished business where the ghosts of the past shimmer still in the present.”

The Colony offers beguiling insights into what it means to be the colonised and the coloniser and is a subtle portrait of character and place. Yet beyond this, Magee’s delicate transporting novel is an impressive celebration of the need for connection.

The Colony by Audrey Magee is published by Faber on 3 February, £14.99

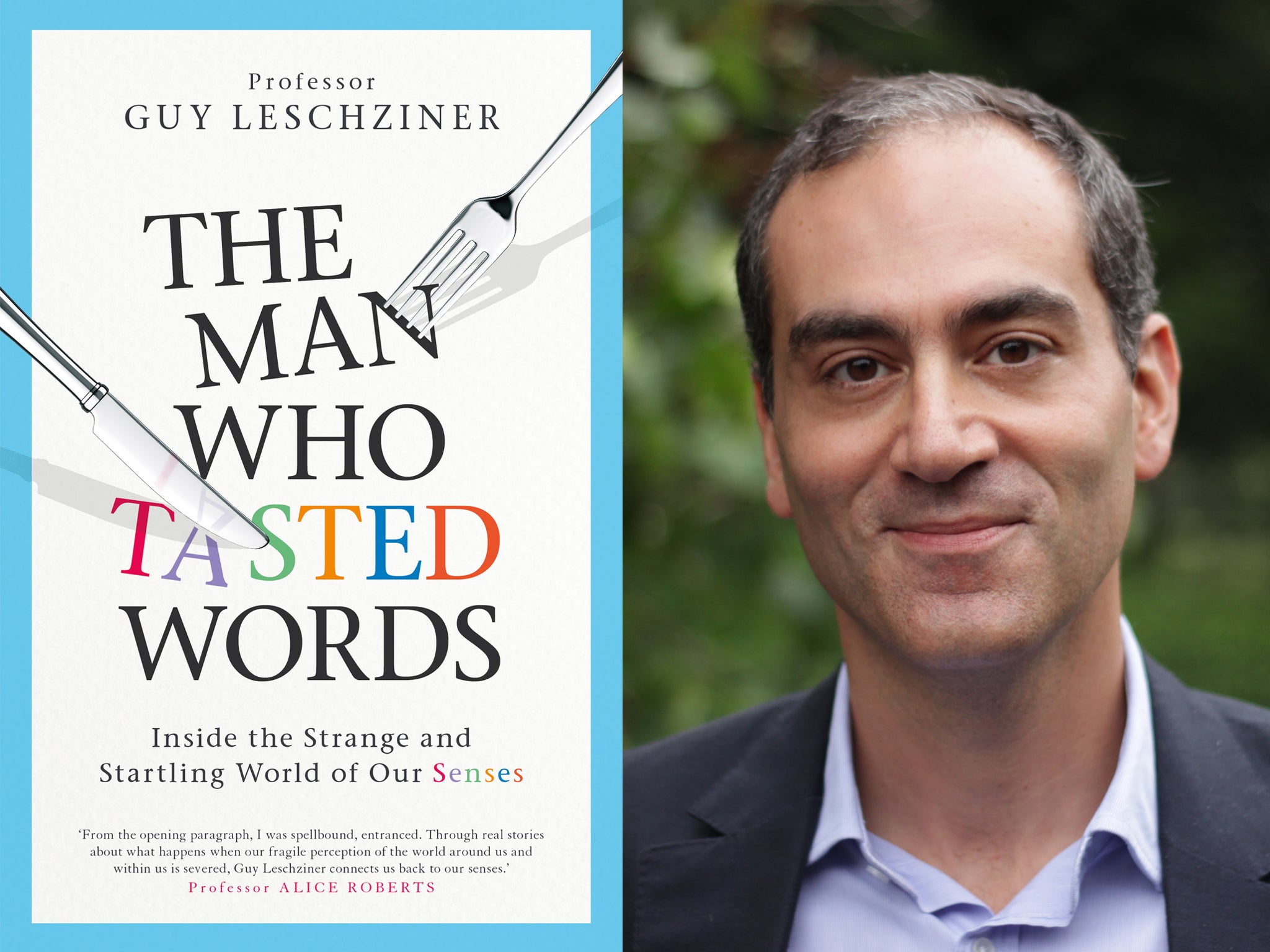

The Man Who Tasted Words: Inside the Strange and Startling World of our Senses by Professor Guy Leschziner ★★★☆☆

In The Man Who Tasted Words: Inside the Strange and Startling World of our Senses, Professor Guy Leschziner explores numerous baffling cases where senses – vision, taste, hearing, smell and touch – start to falter and everything goes awry.

This book was a testing read for a non-sciencey brain like mine, but Leschziner, a consultant neurologist within the Department of Neurology and Sleep Disorders Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, is an engaging guide to a range of intriguing disorders, even though it’s hard to wrap your head around a complex debate about what we perceive to be the absolute truth of the world around us being a virtual reality created by our minds and the wiring of our nervous systems.

The Man Who Tasted Words is full of delights that linger in the mind. I enjoyed the illustration that shows how our brains resolve visual ambiguity, testing the difficulty of easily toggling between seeing “a girl and an old crone” in the same image, even though both are there the entire time.

This profound book is also full of disturbing reflections, including Leschziner’s thoughts on Covid-19. Awful as the pandemic has been, it could have been worse. The professor admits that “the realisation that coronavirus could cause loss of smell and taste” originally raised fears of “a neurological catastrophe”, along the lines of the early 20th-century epidemic of encephalitis lethargica that followed the global outbreak of Spanish flu.

Leschziner states that the symptoms of Covid-19 are probably due to infection of cells within the olfactory epithelium rather than the neurones themselves. “While a number of viruses may enter the brain via this route, it appears that, luckily, Covid-19 is not one of them.” That’s lucky because the Spanish flu mutation killed 1.6 million people and left another five million ravaged by encephalitis lethargica, a condition with symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease.

The Man Who Tasted Words: Inside the Strange and Startling World of our Senses by Professor Guy Leschziner is published by Simon & Schuster on 3 February, £16.99

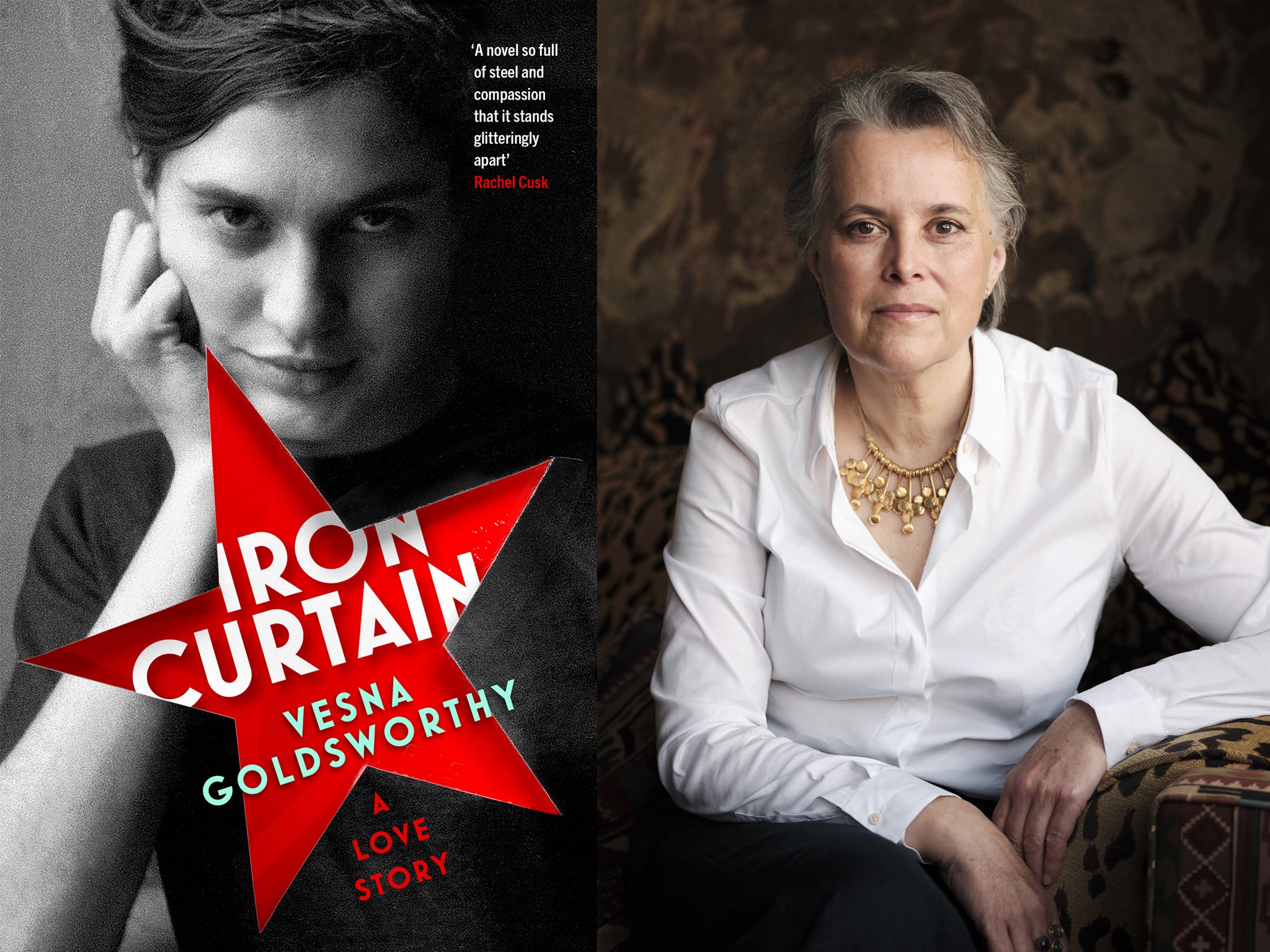

Iron Curtain: A Love Story by Vesna Goldsworthy ★★★★★

Iron Curtain: A Love Story is bookended by two razor-sharp chapters: a prologue that sets up the story of the doomed love affair between Milena Urbanska and the charismatic poet Jason Connor, and the devastating denouement.

Goldsworthy, who was born in Belgrade in 1981, captures the claustrophobic, insulated world of a fictional pre-perestroika Soviet satellite state in descriptions brimming with potency. Milena, a “Red Princess”, the daughter of a hugely influential state figure, is a keen-eyed guide to the grim realities of life, everything from rancid sanitary products to the way that abortion-as-birth control is a fact of life for communist women (Milena’s experience is presented with deadly effect in a simile about a nurse “wheeling a hospital trolley with a row of steel instruments arrayed as though it was some gruesome dessert cart”).

Much of the novel is set in London, where Milena and Jason flee. Goldsworthy, who moved to England in 1986, captures the weirdness of British culture and people in that decade. The constant, telling details about that period ring true: the delights of cheap Italian restaurants in Bloomsbury’s Sicilian Avenue; the efficiency of the Royal Mail (yes, kids, it’s true, there really were two deliveries a day back then); the weird privileged middle-aged men who fetishised Margaret Thatcher. Milena gradually begins to understand the warnings her father gave her about how no one is happy in England. “No one. Not the poor and not the rich. Even their royal family is miserable. I’ve met them,” he told his daughter.

Goldsworthy, a prize-winning poet, also pokes gentle fun at Jason’s scheming and literary pretensions in general. When Milena attends a poetry reading, she notes drolly that it is typical of the “small gatherings of enthusiasts reading, but not always listening, to each other, trading their willingness to be bored for their right to bore”. Ultimately, she also realises that, as he grows more successful, Jason is “a cultural opportunist performing like a circus dolphin”.

Another strength of the novel is the use of weather, which is an almost constant character in Iron Curtain, from the biting cold in Milena’s homeland – where fingers and earlobes can succumb to frostbite – to the “persistent mushy chill” of a London winter. It is all part of the atmospheric feel of a perfectly pitched story that explores big subjects – freedom, artistic truth, family, statehood, integrity and betrayal – with a brilliantly sensitive grace.

Iron Curtain: A Love Story by Vesna Goldsworthy is published by Chatto & Windus on 10 February, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks