Books of the month: From The Raptures to How High We Go In The Dark

Martin Chilton reviews five of January’s biggest releases for our monthly column

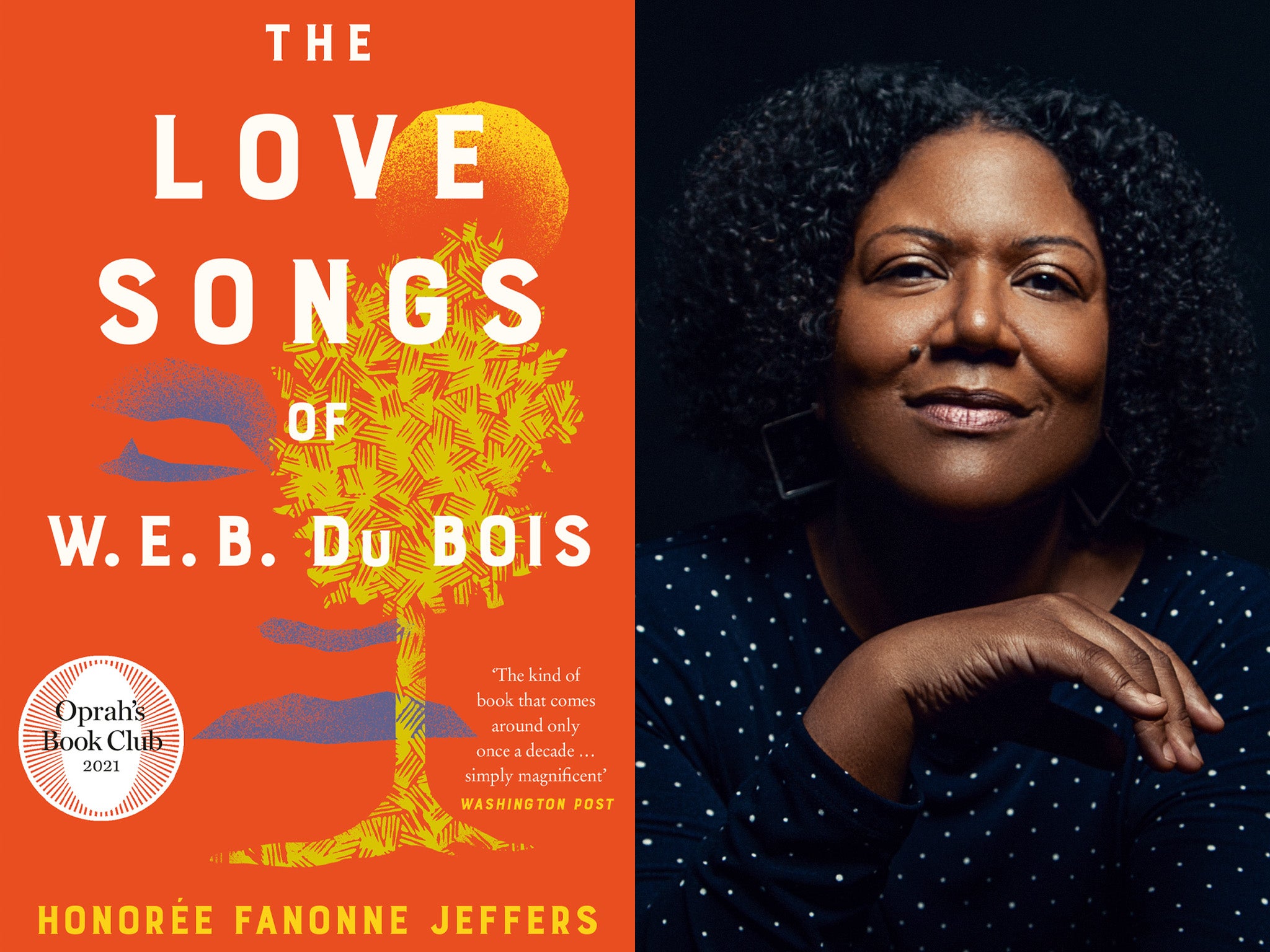

For a reviewer, looking with trepidation at piles of book submissions as deadlines loom, the sight of an 800-page novel can sometimes, in truth, induce a sinking feeling. Happily, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’s epic The Love Songs of WEB Du Bois is mesmerising and a very worthwhile read (full review below).

Three other (shorter) recommended novels this month are Joy Williams’s Harrow (Tuskar Rock Press), a meditation on the end of civilisation after an environmental apocalypse; Isabel Allende’s Violeta (Bloomsbury), the story of Violeta del Valle and the upheavals she endures through a long life; and Louise Welsh’s The Second Cut (Canongate), a stylish, witty detective story set in modern Glasgow. The book, a welcome follow-up to the London-born author’s 2008 debut novel The Cutting Room, again features the memorably reprobate auctioneer Rilke.

According to a statistic in Johann Hari’s Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention (Bloomsbury), the average American spends 17 minutes a day reading books and 5.4 hours out of every 24 on their mobile phone. As the old joke goes, I’d be really productive if only I didn’t keep getting distracted by two things: anything and everything. The way our collective ability to pay attention is rapidly shrinking is the subject of Stolen Focus. Hari – a former journalist notorious for his plagiarism – neatly defines the problems of a social media-obsessed era. In the chapter “The Rise of Technology That Can Track and Manipulate You”, he also offers an alarming account of how the tech companies are in an “arms race to manipulate human nature”.

For decades, Polish-born British Rail ticket collector Anthony Sawoniuk lived an anonymous existence in Bermondsey, keeping secret his past as a Nazi collaborator. In 1999, he finally went on trial for murdering Jews in the Second World War. In The Ticket Collector from Belarus: An Extraordinary True Story of the Holocaust and Britain’s Only War Crimes Trial (Simon & Schuster), Mike Anderson and Neil Hanson tell the engrossing story of a landmark Old Bailey case.

In The Reactor: A Book About Grief and Repair (Faber), therapist Nick Blackburn writes about the death of his father, and about absence and loss in general. It is an original, beguiling book. The one-per-page entries include the ambiguous 11-word aphorism, “It is wild to be alive when your father is dead”.

The quest for an understanding of the mysterious workings of mourning is the subject of academic Michael Cholbi’s Grief: A Philosophical Guide (Princeton University Press), which suggests we view bereavement as an opportunity to grow in self-knowledge. “Self-compassion is a much-underrated virtue,” writes Dr Gavin Francis in the small, sparkling Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence (Profile & Wellcome Collection), which is full of uplifting stories of healing.

Finally, White Debt: The Demerara Uprising and Britain’s Legacy of Slavery (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) sees author Thomas Harding argues that “the roots of today’s systemic racial inequality are found buried in Britain’s colonial past”. Harding focuses on the 1823 rebellion of enslaved people in the British colony of Demerara (now Guyana), and he also looks at the dubious past of his own ancestors, who made money from slave sugar plantations.

Novels by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, Jan Carson, Sequoia Nagamatsu and Faysal Khartash, Roopa Farooki’s memoir of life as a doctor and a book of essays about the experience of being an Asian in Britain, edited by Helena Lee, are reviewed in full below.

The Raptures by Jan Carson ★★★★☆

Jan Carson, winner of the EU Prize for Literature for her second novel The Fire Starters, grew up in a small village in Northern Ireland. The Raptures, set in fictional Ballylack, is a searing exploration of trauma in a small Ulster town, a tale centred on the repercussions of a mysterious “dreadful disease” that kills young children in the summer of 1993.

Against a backdrop of sectarian violence and religious suspicion, Carson conjures up a fascinating tale of trauma, fury and everyday panic, as ordinary people fall prey to the power of rumour. Hysteria is contagious in The Raptures, a novel originally called No Promised Land.

Carson writes with sardonic wit about unimpressive middle-aged men. The epitome of this limited bunch is the morose Alan Gardiner, a man who can only imagine his wife naked if she is “cooking a fry”. He is at the centre of the mystery of the deaths, a puzzle that is resolved in a believable twist. Carson cleverly depicts the reality of rural existence in a “lonely, raining place” through the eyes of two outsiders: Gardiner’s wife Maganda Rosamie Mendoza, who has moved to Northern Ireland from the Philippines, and her son Bayani, a boy “actively and furiously hated” by his father.

As well as dissecting small-town hypocrisy, there are interesting aspects of magical realism in the novel – particularly in the plot line around 11-year-old Hannah Adger, a survivor who sees visions of her dead classmates – and Carson explores the folklore and superstition still embedded in a modern Ulster community.

Tellingly, it is Bayani, always just called “Ben” by complacent locals, who tries to explain to Hannah why Ballylack is a place that’s afraid of anything different and scared of honesty. Ballylack is a judgmental place. Even as the funeral parlour owner is preparing the body of one of the dead children, he is secretly musing about her lack of prettiness, saying, “there’s always been a rodent look off her.”

The Raptures, which also skewers modern “vulture” journalism, is a sharp novel, with mordant things to say about the effects of religious zealotry (and the many forms it takes in modern Ulster) on young, vulnerable souls.

The Raptures by Jan Carson is published by Doubleday on 6 January, £14.99

How High We Go in The Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu ★★★★☆

Any 2022 reader will surely shudder at the words “it might be a new strain”, a warning written a year or more before Covid-19 by Sequoia Nagamatsu for his wildly imaginative, pandemic-prescient novel How High We Go in The Dark.

Make no mistake, this is an unsettling read. The novel follows a set of intricately linked characters over hundreds of years, as humanity struggles to rebuild itself in the aftermath of an “Arctic Plague” that spreads from the sludge dug up by a prehistory research team who are investigating Siberia’s melting permafrost.

This fictional plague hits America in 2030 and Nagamatsu, who was raised in the San Francisco Bay area, depicts his homeland’s reaction to a deadly virus with a droll eye. People pay for food “with mortuary cryptocurrencies tied to ad-ridden phone apps”, Elegy Hotels spring up, there are gold coffin awards for “Most Promising Funerary Start-Up of 2040”. Most chillingly, there are City of Laughter “euthanasia theme parks” where staff who put terminally ill children to sleep are told that it’s “imperative you exude merriment”. Far-fetched? Alas, it no longer seems so.

Back in 2015, Nagamatsu said he was intrigued by the idea that in a big corporation, “someone is deciding who will have access to certain medicines”, and the scientific ramifications of a pandemic are explored in a satirical chapter about a heartbroken scientist searching for a cure who inadvertently creates a talking pig. Fake cures to the Arctic Plague spring up among religious communities. “People in the Bible Belt are baking themselves in the sun, thinking they can burn it away,” notes one character.

The novel also has telling things to say about the immigrant experience in America. One character, who “rarely spoke in class because I was ashamed of how I sounded”, reflects on the “stereotypical Silicon Valley Asian family experience”. He recalls going to comic book conventions to pick up women, because it’s full of girls “who think you look like some anime character”.

Although the novel loses impetus in the last section, which centres on a cosmic quest to locate a new home planet, striking images come thick and fast early in the earth-bound sections: people with open pustules, burnt-out fields littered with the husks of dead horses, people with glowing insides. How High We Go in The Dark is a terrifyingly original novel, but a tough read during an Omicron surge.

How High We Go in The Dark by Sequoia Nagamatsu is published by Bloomsbury on 18 January, £16.99

Roundabout of Death by Faysal Khartash ★★★★☆

According to official UK government immigration statistics for 2013, the number of Syrian nationals fleeing to these shores more than tripled, “which is consistent with continuing civil unrest in Syria since early 2011”, they reported.

If you want to understand why someone would risk everything to leave their homeland, even one they love, then Faysal Khartash’s moving, tender novel Roundabout of Death (translated by Max Weiss) offers some answers. The title, incidentally, refers to a notorious crossing point between districts of Aleppo held by different factions.

Khartash, who was born in 1952, is a leading Syrian author who also works as a schoolteacher. His beautiful portrait of the reality of daily survival in his native Aleppo is set in 2012 during the civil war. His tale unfolds through the eyes of a disillusioned middle-aged teacher called Jumaa, a man prone to cheery observations such as, “I saw her with my two eyes, the same ones the worms will feed on one day.”

It is little surprise that there is a morbid quality to Jumaa. In this diary-like novel, he portrays a ravaged Aleppo in which young men “toss around grenades”, a city blighted by pill popping, water shortages and rampant, brazen corruption. When Jumaa gets into trouble at the Bustan Al-Qasr checkpoint, he escapes repercussions by pressing cash into a policeman’s hand. He knows he must be careful: critics of the regime are often summarily executed.

In the potent chapter, “We Grill and Grill and Don’t Even Make Back the Cost of the Coals”, Khartash offers a mouth-watering description of a food stall in Bab al-Hadid Square. “Little birds started chirping in my belly” says Jumaa when he sees the kebabs, pita bread and biwaz salad. Amidst the tranquility, his head is filled with horror and destruction as he remembers his sister’s grief at the death of her husband “shot in the neck by sniper fire”, a man who “fell down without saying another word”.

The book captures the arbitrary craziness of life in Syria. One man is shot in a row over cigarettes. Children as young as 10 are dressed in camouflage and carry Russian-made rifles, serving as Islamic State fighters. “We endure this horror every day, this raving madness,” writes Khartash, in what is a sublime distillation of one of the tragedies of the early 21st century.

Roundabout of Death by Faysal Khartash is published by Head of Zeus on 20 January, £14.99

Everything is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Pandemic by Roopa Farooki ★★★☆☆

In Everything is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Pandemic, Dr Roopa Farooki casts a trained medical eye over Boris Johnson’s body – “looks like a vasculopathy, stiff arteries, fatty liver and pre-diabetes” – but it is also his ailing soul that comes under scrutiny in her coruscating account of what it was like to be on the NHS frontline in the first 40 days of lockdown in early 2020.

The prime minister is, in her words, a “smug mop-headed bastard”, “mendacious” and a “blonde muppet” (all descriptions written before his Christmas party chicanery was exposed). In her entry for day seven of lockdown, she castigates Johnson as “the idiot who told the nation to take it on the chin, just a few weeks ago. Not your PM. The majority voted for him in a Boaty-McBoatface landslide of irresponsibility, because he gives good caricature.”

It is hardly a surprise that politicians who just “spout platitudes” should arouse such derision in an exhausted doctor working 13-hour shifts in dangerous conditions, where lack of proper protective equipment was killing her colleagues. One medic is sent masks by her family in China “who are providing her with better protection than the NHS”, notes Farooki, the author of six previous novels and a writer listed three times for the Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Grief is the backdrop to the book. Farooki’s sister Kiron died of breast cancer in February 2020. “Maybe she just beat the queue,” notes the doctor sardonically. The book, with its urgent, compelling tone, puts you right inside a horrific situation, one that was almost changing in real time as she writes. The attitudes of the first week of lockdown, when “the consultants laughed when one of their number wore a mask to a meeting” quickly turns deadly and dismal. “You saw patients’ relatives stealing the hand sanitiser from the end of the bed, the same stuff that you need to keep their loved one safe,” she notes.

The clap for the NHS also gets short shrift. “You feel that it’s a way to fake support without any cost to the clapper,” Farooki writes. “I’ll take the praise, said one of the porters, working the night shift, but I’d prefer cash.”

Farooki, who was awarded the Junior Doctor Leadership Prize for her work during the pandemic, is smart enough to acknowledge that “everyone is writing a diary, you realise”, during a crisis that offers opportunities to “media-hungry opportunists”. Even if there is self-advancement involved, it is still worthwhile to have an eloquent inside account of such a historic time, especially one that holds politicians to account for what she calls “criminal negligence”.

Everything is True: A Junior Doctor’s Story of Life, Death and Grief in a Pandemic by Roopa Farooki is published by Bloomsbury on 20 January, £14.99

East Side Voices: Essays Celebrating East and Southeast Asian Identity in Britain (Edited by Helena Lee) ★★★★☆

East Side Voices: Essays Celebrating East and Southeast Asian Identity in Britain contains 18 highly personal, revealing essays by writers – including Anna Sulan Masing, Tuyen Do and Helena Lee, who edited the collection – that open a window on the dehumanising consequences of racism and stereotyping for Asians growing up in the UK.

Claire Kodha, a half-Japanese professional violinist from Margate who has written a novel about a mixed-race vampire, reveals how painful it is as a teenager to see Asians “mocked and dehumanised in film and TV” and Asian women “sexualised and objectified” on the internet. Kodha also faced racism on a more personal level, with her “mum’s accent mimicked incessantly and inaccurately by English people”.

In her essay “Battle Ground”, Romalyn Ante, a Filipino-born Wolverhampton-based poet and specialist nurse, talks about some of the shocking prejudice she and her sister have faced working for the NHS. Sometimes the hate is on open display in the streets. In her witty essay “Vector of Disease”, Zing Tsjeng discusses stereotyping along with what it’s like to be casually greeted with “Alright, ching chong?” by a stranger on the street. She also delves into the absurdities of men with “an Asian fetish”.

There is also a compelling, candid essay from Dundee-born Katie Leung, who played Harry Potter’s love interest Cho Chang in the film adaptations. “It’s mad that at the age of six, I was already trying to please white people,” writes Leung, whose parents were from Hong Kong. She muses movingly about being aware of her “Chineseness” in primary school and the problems of acceptance when you come from a community with different traditions. “My gran grew vegetables in the back garden, and she would fertilise them with our urine,” recalls Leung. “She kept an ice cream bucket in the toilet to collect it, and I would think, f***, if my white friends come to my house, they are going to freak out.”

This important book, which is full of wit and insight, sheds light on aspects of racism that are often overlooked and it offers welcome exposure for a collection of voices that are too often sidelined from the cultural mainstream.

East Side Voices: Essays Celebrating East and Southeast Asian Identity in Britain (Edited by Helena Lee) is published by Sceptre on 20 January, £14.99

The Love Songs of WEB Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers ★★★★★

Poet Honorée Fanonne Jeffers set out to write a sweeping epic about “southern Afro-Indigenous women’s lives and their extraordinary place in the trajectory of American history”, and she achieves this and more in her magnificent debut novel The Love Songs of WEB Du Bois.

The history of slavery is at the core of a story set in a fictitious Georgia town called Chicasetta. At the centre of the tale is the black feminist Ailey Pearl Garfield. We see her blossom from a naïve high school student in the 1980s into a fearsome academic. By 2007, she is questioning the world as she tries to come to terms with her own complex “interracial family situation”.

Among her ancestors is Samuel Pinchard, the overseer for nearly one hundred slaves on a 19th-century tobacco plantation. He was a sexual predator, enabled by the society in which he flourished – including the hypocritical “churchgoing souls” – to buy and sexually abuse young girls. Samuel was an early “spiker”, using poppy syrup to drug his child victims.

Like Jeffers, Ailey is fascinated by old family stories – and there are a lot of them in a dense and detailed 800-page story. There is a touching section in which Ailey interviews old people from Chicasetta. They tell her about growing up in early 20th-century segregated America, a time where white men were able to murder black men “like it was Judgement Day”.

Amid all the pain, Jeffers serves up lots of humour. The author of five poetry collections has a gift for language that shines through – one deadbeat is described as “a man stewing in the juice of mediocrity” – and she brings wit to Ailey’s grubby experiences with young men. “Chris was a good kisser, but his other idea of romance was to grab my breast with one hand and pump it, as if seeking pasteurised, whole milk,” she says.

Ailey is a spirited central character, always ready to fight against “sexist crap”, especially the attitudes she encounters at the conservative Routledge College. Jeffers, who teaches creative writing and literature at The University of Oklahoma, is wry about Ailey’s ability to mock stereotypes. “I put extra cornpone and molasses into my voice,” says Ailey as she tries to schmooze an academic.

Sexual violence and abuse, and the life-long damage it inflicts, is a major theme of the book. Ailey and her sisters Lydia and Coco are all abused by their grandfather Gandee and spend years “keeping that s*** hid”. It’s pitiful to see the way drugs get a hold of Lydia’s life. Yet the story is about survival, as Coco remarks, “I just had to say, f*** it. I gave Gandee the first part of my life. I’m not gone give him the rest.”

The book is overflowing with touchstone references – singers Lena Horne and Luther Vandross, filmmaker Spike Lee, activists Martin Luther King and Ruby Bridges (the girl who changed history by attending a segregated school in Louisiana and who was immortalised by artist Norman Rockwell) – and these prominent African-American icons are blended into the story neatly along with numerous thought-provoking discussions about the role of race, class and skin colour in American society and within the black community.

One haunting image remained in my mind long after reading the novel. Jeffers details the wretched story of Slave Number 319, who was parted from the love of his life at a mass auction of human beings. She describes what it was like to see the poor man “weep inconsolably as his lady was sold away separately”, before adding the biting coup de grâce: “The rain had been unceasing.”

The Love Songs of WEB Du Bois is a challenging read, but it’s a splendid one.

The Love Songs of WEB Du Bois by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers is published by 4th Estate on 20 January, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments