The ‘Ozempification’ of the British novel is here – but only a true talent can write a great slimmed down book

This year’s Booker Prize winner ‘Orbital’ by Samantha Harvey is markedly short but there is one reason it stands as a novel and not a novella, says Robert McCrum, and is proof of what it takes for pocket fiction to hold its own against longer tomes

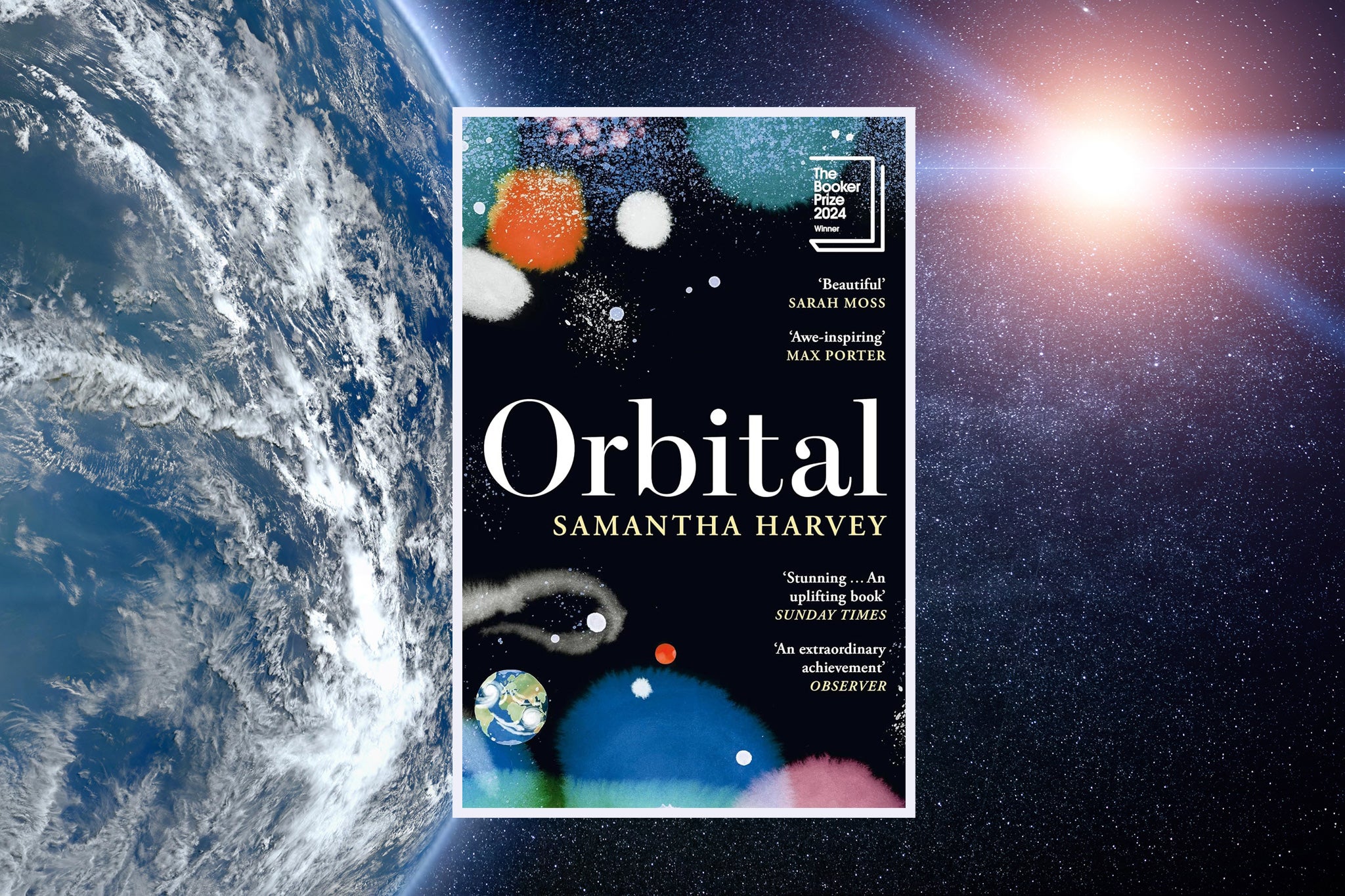

When Orbital, a tale of some 136 pages, by Samantha Harvey, the 2024 Booker Prize winner, landed on my desk, my first thought was for an old friend, an acclaimed English writer, now in the twilight of his career. His latest novel, still unpublished, is said to weigh in at more than half a million words.

Strangely, that head-spinning statistic is matched by the giddy sensation of opening Orbital. As light as a volume of poetry (which it occasionally resembles), this pocket fiction must be the ultimate slim volume. More, the out-of-body experience of reading it – something you could easily do during a lazy afternoon – is as heady as an exotic drug. The tale of six astronauts rotating their spacecraft 250 miles above our planet, Harvey’s narrative floats free in the weightless and uplifting cosmos. (Add a space-odyssey soundtrack like that Strauss waltz, The Blue Danube, and you’d have an audio-visual treat.)

With Orbital in hand, however, there’s the sneaking anxiety that it may be just a bit too brief, and too fleeting in its claim on our attention. It’s no big confession to admit that, as common readers of the novel, we are creatures of an English canon that’s the polar opposite of undersized. Consider – if you’ll allow a trainspotting aside – some literary statistics.

As recently as 1993, Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy, a volume that had already been reduced, by editorial weight loss, from a first draft of close to a million words, tipped the scales at 1,504 pages. On publication, many critics, dazzled by Seth’s prodigal gifts, and reaching for superlatives from old times, compared his achievement to Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa; or, The History of a Young Lady. This epistolary novel of 1748, hailed by Dr Johnson as “the first book in the world for the knowledge it displays of the human heart” clocks in at approximately 970,000 words, in several volumes. Next to A Suitable Boy, only Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace or perhaps The Unconsoled, Kazuo Ishiguro’s masterpiece, comes close.

In the days before television and the boxed set, of course, the English novel, tending towards gravity, would usually appear in three, or more, volumes. That’s what the market required. Tristram Shandy (190,000 words in nine volumes), Emma, Jane Eyre, Bleak House, Vanity Fair (180,000 words) and Middlemarch (316,000 words) are all “long reads”. From those simpler, more leisured times, perhaps only Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (some 72,000 words) achieves a length we might find familiar.

Gravity and fiction, then, go together like ham and eggs, and did so, uninterrupted, until the millennium. Sample a list of Booker prizewinners from 1980-2000, and you’ll find nothing close in length to Orbital. For instance, Midnight’s Children, Oscar and Lucinda, The English Patient, and Possession: these titles average more than 300 pages, and if they are substantial in volume, they are also highly complex and original in point of view, style, landscape, and character, combining funny and sad. It’s always been true of English fiction that anything goes.

There’s nothing predictable, restricted or conventional about any of these novels. They share the literary DNA of the classics I’ve already mentioned and are part of a varied library of long and short fiction. Alongside the tradition of gravity and grandeur, there’s a rival strand, books that show the opposite, revelling in brevity, and a mastery of concision.

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a classic of this genre. Animal Farm, a novella that George Orwell originally subtitled “a fairytale” is another. Writers such as Ian McEwan, JM Coetzee and Damon Galgut can also be found on this shelf. Earlier in the 20th century, both Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene were accomplished masters of the short novel. Today, few would dare to call The Loved One a novella.

Forget the naysayers, the logic of this decision was impeccable. How can you claim to be the premier English fiction prize if you exclude new writing from the most dynamic expression of contemporary book culture?

In the end, it was the evolution of the publishing industry that changed the terms of trade in fiction. The Eighties saw the mergers and acquisitions that transformed a cottage industry into a glossy global marketplace in which every aspect of the printed word became monetised in ways hitherto unknown. Just as football became transformed beyond recognition by the Premier League and telephone-number salaries, so the end of the Net Book Agreement took the world of books into an international marketplace driven by an unprecedented English language boom.

By the turn of the millennium, this cultural change was yielding a literary dividend. The novel, which has always held a mirror up to society, had begun to acquire new forms and new voices. Manga fiction boomed. Women writers worldwide finally began to receive their long-overdue recognition. In the marshes beyond Grub Street, a new creature beloved among publishers – the “contemporary classic”, a second cousin to that notorious impostor, the “instant classic” – began to flounder from the swamp towards the marketplace, its path made easier by new technology and social media.

In the midst of this ferment, a new and troubling question began to be ventilated at book festivals, university seminars and editorial meetings. Was the Great Tradition – the Leavis canon itself – no longer relevant or fit for purpose? Had we not reached the long-predicted moment when we could solemnly pronounce “the death of the novel”?

More radical still: was non-fiction now the new fiction? Many good writers have argued the case for the upgrading of non-fiction. No one, so far as I know, has mastered the most obvious objection. Despite every effort, “fiction” continues to be a distinct and recognised genre while “non-fiction” remains an archipelago of disparate categories such as history, biography, reportage, etc. Nonetheless, it’s plain that, in this new century, the life, fate, and identity of the English novel are very much up for grabs.

Indeed, the Booker Prize itself has made a decisive contribution to this debate. Ten years ago, in 2014, amid howls of protest, and dire predictions of imminent literary doom, the prize extended its range from the annual consideration of British, Irish and Commonwealth fiction to include English language novels worldwide. Most contentious of all, the prize opened its doors to submissions of new American novels from the United States.

Forget the naysayers, the logic of this decision was impeccable. How can you claim to be the premier English fiction prize if you exclude new writing from the most dynamic expression of contemporary book culture? To date, the sky has not fallen, nor the Earth become detached from its axis. The Booker Prize – like all the world’s principal book prizes – shows every sign of being quite at home with its annual judging the English novel. Which brings us, full circle, back to Orbital.

Samantha Harvey and her space travellers float far above the quakes, hurricanes and typhoons of the planet famously dubbed “the good Earth” by the Apollo astronaut Michael Collins. During 16 orbits of the silent planet, these pioneers of the cosmos do what writers do – they watch and record, describing the awesome beauty of Earth in the course of a single day.

In this mode, from some points of view, Orbital is a triumph of non-fiction, a work of brilliant reportage. Its six protagonists – Pietro, Chie, Anton, Shaun, Roman and Nell – are real enough as quite ordinary characters spinning through outer space in a tin can, but they do not have – how can they? – the depth or complexity of Clarissa Harlowe, or Dorothea Brooke. But that’s not Harvey’s first concern. She is asking those questions that Paul Gauguin first framed on a famous canvas in 1898. Where do we come from? Why are we here? Where are we going? On board the International Space Station, these blur into an even bigger, more topical, question: what is life without Earth?

Orbital is not Heart of Darkness and does not want to be. It is, however, as much a phenomenon of its time as Conrad’s masterpiece – a strange and rare, at times oddly beautiful invention, the imaginative realisation of a unique moment of empathy, Harvey’s remarkable insight into the meaning of life beyond Earth. That’s probably what will justify Orbital’s long-term claim of a place in the tradition of English fiction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks