The UFO files and why life at the edge of the universe is becoming clearer every day

As the Pentagon’s latest report on UFO’s reveals hundreds of new reports of unidentified and unexplained aerial phenomena, author of Alien Earths and Cornell university astrobiologist Lisa Kaltenegger explains why there are 40 billion possibilities for worlds like ours just in our galaxy

We know that one out of five stars has a planet that could be like the Earth’s. It’s incredible. One in five – and we have 200 billion stars in the Milky Way, alone. So there are 40 billion possibilities for worlds like ours just in our galaxy.

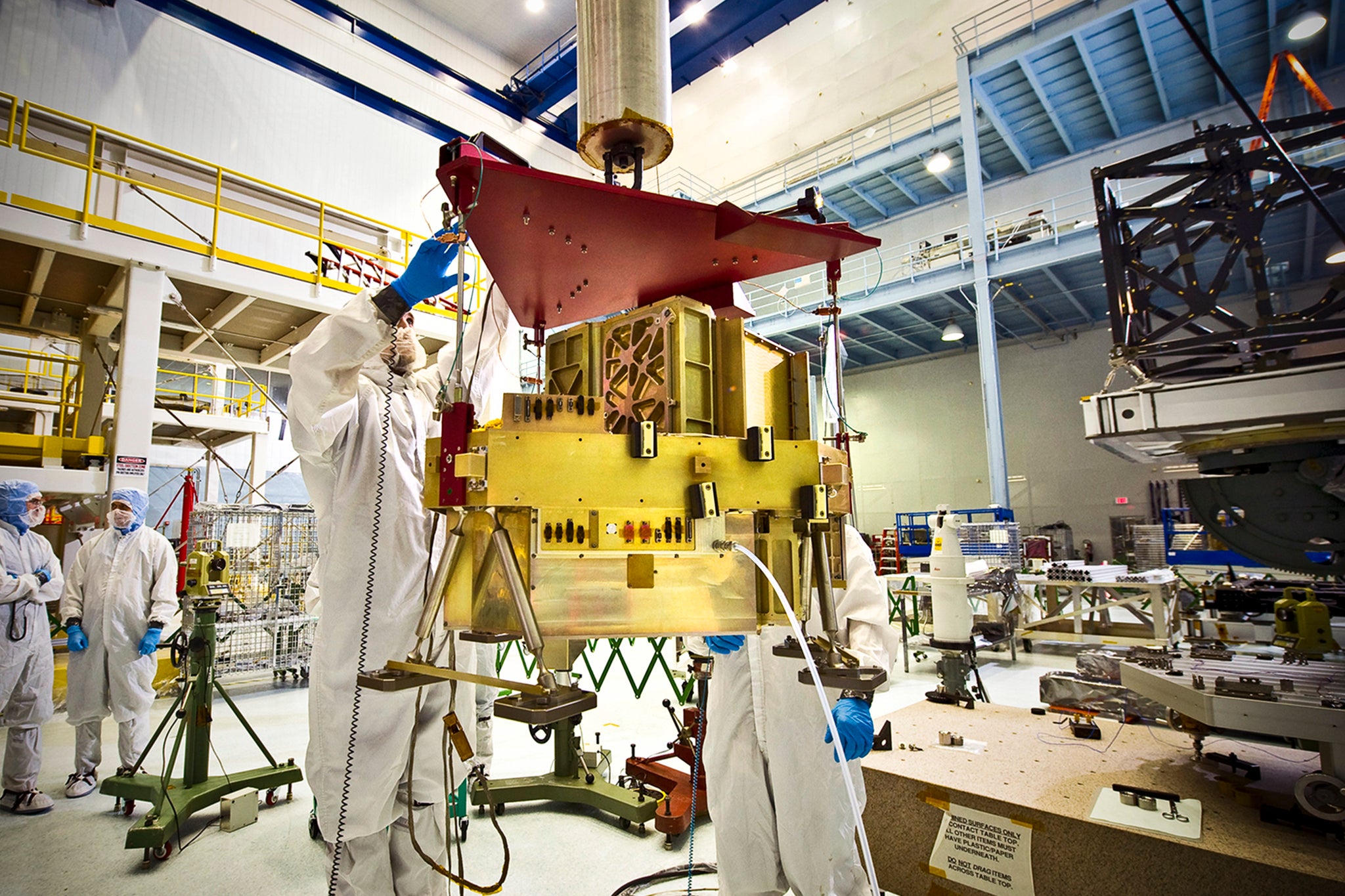

I’m part of the Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) team, which is one of the instruments on the James Webb Space Telescope. We are looking at the Trappist-1 system right now – the first rocky worlds that are within this habitable zone. So, we’re already looking at some worlds that could harbour life.

Right now we are concentrating on gases – what’s breathing in and out. It’s like when you go into the forest and see footprints. You can say, ‘Oh, this is definitely a deer.’ But if you see something else – smudges in the dirt, for example – it could be life, but it could be something else.

So we make our telescopes look for life as we know it – while keeping our eyes open for anything weird or unexplained. You have to be very careful about interpreting signs of life that you don’t understand because there are other explanations like a kind of geology that’s not part of our planet and that you just haven’t thought about.

Life on Earth needs water, but water alone isn’t enough... Hopefully, we will find oxygen, but oxygen alone is not enough either. We’d also expect to find methane.

This is why early on I started to make these models of Earth through its geological time to figure out how long you could have spotted this life fingerprint here. Nobody had done this before. How long could you have seen that Earth was a habitable world? We came up with 2 billion years, because that’s how long the combination of oxygen and methane left an imprint in our air of life on this planet.

So we are on the verge of being able to spot life in the universe because, for the first time, we know so many planets exist and we know where the closest ones are. We also know that on a planet like Earth, for about 2 billion years, you have to look at both the air and the atmosphere.

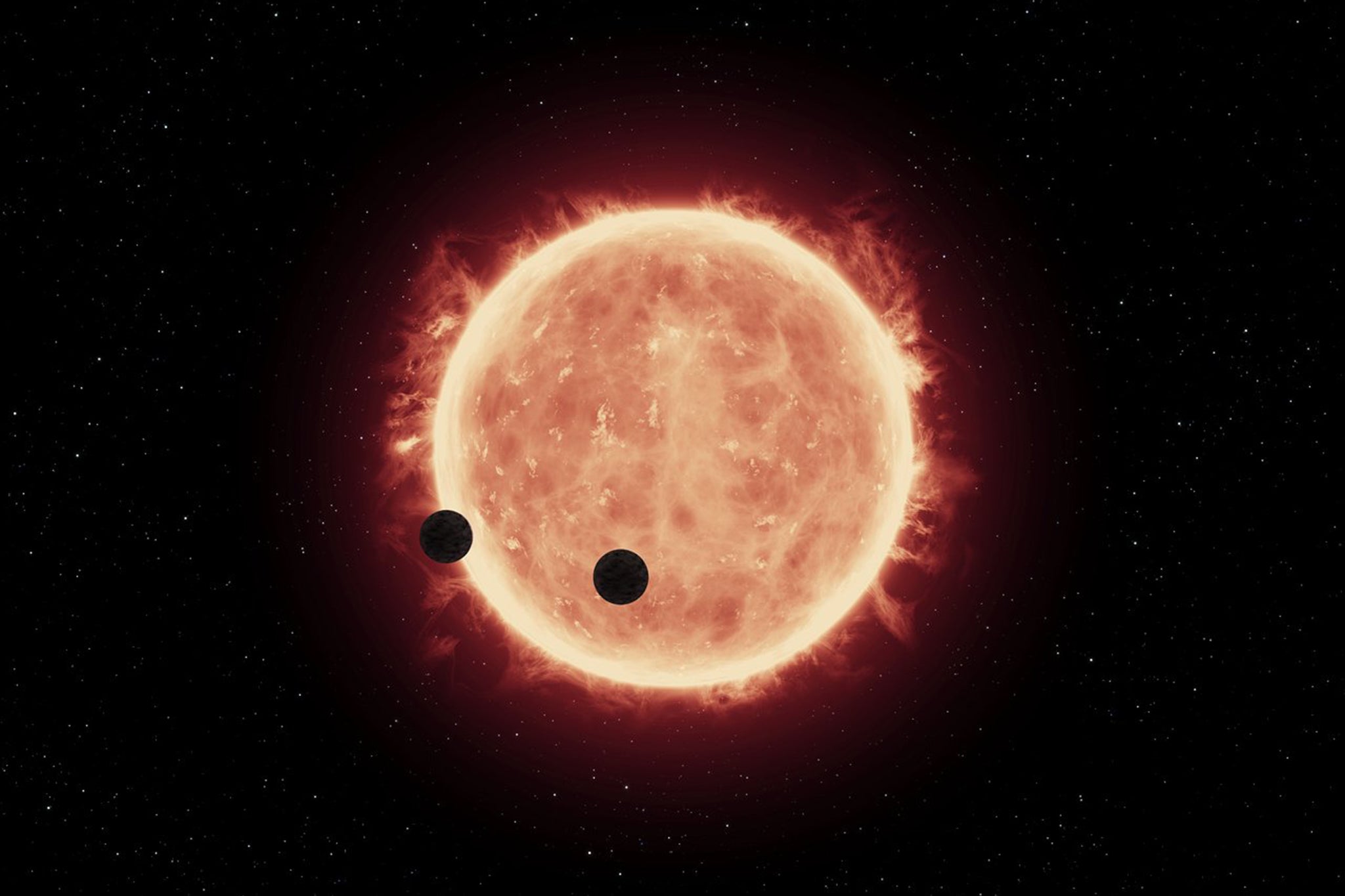

With the James Webb Telescope, a space observatory designed to detect infrared radiation from solar system objects, we can only look at the air of a planet which has to pass between us and its star, and then the starlight gets filtered through the air of the planet.

That light gets to my telescope after it’s been filtered through the planetary atmosphere. The molecules that the light hits all have different structures; they require a different energy – a different colour of light to swing and rotate, so by looking at which colour is missing, I can tell you what’s in the air of that planet.

I can’t see the surface of the planet, because if light hits the surface, it bounces off and doesn't go straight through my telescope. So for now, we are limited to searching for the air and the gases.

The next generation of telescopes we’re designing – called the Habitable World Observatory – are bigger than the James Webb and those missions are planned for somewhere around 2035/2040. Then we would want to learn more about the planet, about its surface, what colours we can see, and bring those lines of evidence together.

When you look at the Earth’s evolution, the more oxygen we had, the bigger and more complex life got. So if we find a planet with 30 per cent oxygen, like when the dinosaurs were around, we would expect big or very complex creatures. And I think the headline would be: “The new era of humankind – we are not alone.”

It would be such an incredible find and I think that humankind would see this as its biggest adventure. The scientific community is international and scientists are interlinked – countries would pool their resources to build one really big telescope.

The further you look away, the further you look back in time... So these worlds are lost to us just because of the vast distances and the time that it takes light to travel. But luckily, there are so many worlds close by. I have a section in my new book in which I ask “Where are the aliens?” – aliens who could be looking at us.

If we assume there could be life out there and if they have our level of technology, then they could have spotted life on Earth. Sometimes I wonder, what if there’s a cosmic reality TV show, and they’re saying, “Oh my God, they’re destroying the ozone layer. Then… go planet! You fixed it! That would be one episode. Then in another, they’d say, ‘Oh my God, they're destroying the climate, come on planet!’”

If another civilisation were to find us, hypothetically, it could be a hundred light years away and so they’d see us while we’re just starting to use radio. We don’t have spacecraft. And so then the question becomes: why haven’t they come here? Well, I just don’t know if we’re that compelling. I love our planet, but it’s funny that the underlying assumption is that everybody would come immediately and talk to us.

I think by trying to find life or other Earth-like planets, whatever we learn out there actually helps us to understand our own planet down here and to safeguard it better.

When I get home after work, sometimes I get to watch TV and really enjoy the new Star Trek and Stargate. There was an episode in which the spaceship went through the galaxy looking for other planets.

They were standing on the bridge and were saying they’d just taken the light spectrum off this planet and that they could see oxygen, methane and water. And a friend of mine called to say they’d just seen me standing on the bridge. I was like: I want to be there. I want to stand on that bridge.

Do I think we’ll discover a planet that could harbour life in our lifetime? That’s why I’m working very hard on this, trying to make this happen. And there are lots of people who are doing the same...

People have high hopes that what we’re finding with the Trappist-1 system could mean something, that this could actually be the first indication of an interesting biochemistry that might or might not indicate life. But the excitement is there, and for the first time, the instrument – the capability – is there.

The biggest surprise would be if we find nothing.

As told to Alex Hannaford

Dr Lisa Kaltenegger is the founding director of the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University. Her new book is ‘Alien Earths: Planet Hunting in the Cosmos’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks