How to deal with the most difficult festive breakup of all

It’s the devastating split that few of us will escape – especially at this time of the year. Luckily, Robert McCrum is here to counsel us through the loss and grief that comes with saying goodbye to our old books, and to offer advice on deciding which ones should go and which should stay

There’s no breakup like the breakup of your books – your library. Everyone I know seems to be in the throes of shedding books, and suffering a self-inflicted nervous collapse. A pre-emptive strike before some feisty new year resolutions, perhaps; or the worst part of a divorce, that midlife house move, or downsizing after the kids have fled the nest. Unthinkable, no doubt, but as inevitable as death and taxes.

At this point, I must invite mystified Kindle readers to experience this column as anthropologists who have just strayed into the company of a remote, forgotten, and possibly savage tribe: bibliophiles who worship the rare and beautiful mystery of the hardback (or paperback).

Saying goodbye to treasured titles is a rite of passage that elicits something akin to grief, an emotion that notoriously requires many cycles of recovery (denial, anger, depression, and so on). That is not altogether surprising. Our books amount to an unofficial autobiography, expressive of some primal drives: vanity, pride and ambition. So, how do you choose which ones should go and which should stay?

I’m looking at a faded Penguin edition of Animal Farm (price 1/6, or 18 pennies), a gift from my father when I was about 11. An indomitable survivor on my shelves, with yellow pages and a broken spine; the first classic of English literature I remember reading in bed. When I recall the tickle of the covers on my bare legs, the combination of Orwell and that scratchy blanket seems apt. Of course, the Orwell I read now is not the Orwell I read as a teenager. That’s another part of the way books become braided into our hearts and minds, through the reiteration of their stories.

Not all the titles you might consider discarding are classics. Besides, what is a classic anyway? (Italo Calvino has a useful definition: “A classic is a book which has never exhausted all it has to say.”)

A much-fingered edition of Wisden might seem as precious to some as the first volume of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. The marginalia in my A-level Arden edition of Macbeth is embarrassingly sophomoric, but it does bring back Mr Rosser’s interrogation of “the Scottish play”, and the wooden benches of his classroom.

The whirligig of time inflicts its own indictments, the grim verdict of shifting fashion. For instance, travel books by Patrick Leigh Fermor, Paul Theroux, or Jonathan Raban, and translations of nearly unreadable Serb novels, now seem – how shall we put this? – less essential than before.

Twenty years ago, I completed a life of PG Wodehouse. Now, when I survey my bursting PGW shelves, I get a snapshot of the happy years – 2000-2004, when I researched his biography – and instantly feel more content in several quite obscure senses. Wodehouse himself published about a hundred books of sublime comedy. Many, but not all, are classics. Am I ever going to re-read all of the Jeeves and Wooster stories? Probably not. Still, I’d fight you in a ditch for those editions.

The irrational moods inspired by our books are another reminder that the hardback sentinels on our shelves define and encrypt our inner lives in all their messy contradictions. Is this why we are so magnetised by our friends’ libraries? For the clues they offer into an unpoliced version of a secret soul?

After this tormented preamble to the moment of truth, it’s time to make your mind up; for the nitty-gritty. Who, or what, is for the chop? One word of warning: discarding those favourite authors from your fascinating and precocious adolescence – Mervyn Peake, Herman Hesse, DH Lawrence and Robert Musil – is a rookie error. You’re still just scratching the surface. A colder, more prejudiced elimination will be required.

While you are asking yourself why on earth you once acquired The Bone People or Vernon God Little, you might want to browse some of the cover copy (puffs, plugs and quotes) adorning your hardbacks. Certain phrases might strike you, in the cold light of December, as ripe for peremptory retribution.

In my Maintenance Guide to the Modern Library, any blurb that describes the contents of a book as “haunting” or “heartbreaking” inflicts a fatal curse. (We all have our bugbears: one strong-minded friend will never respond to a blurb that includes “Glaswegian”.) “Instant classic” is another kiss of death. And so are “unputdownable”, “awe-inspiring”, or “I laughed out loud”.

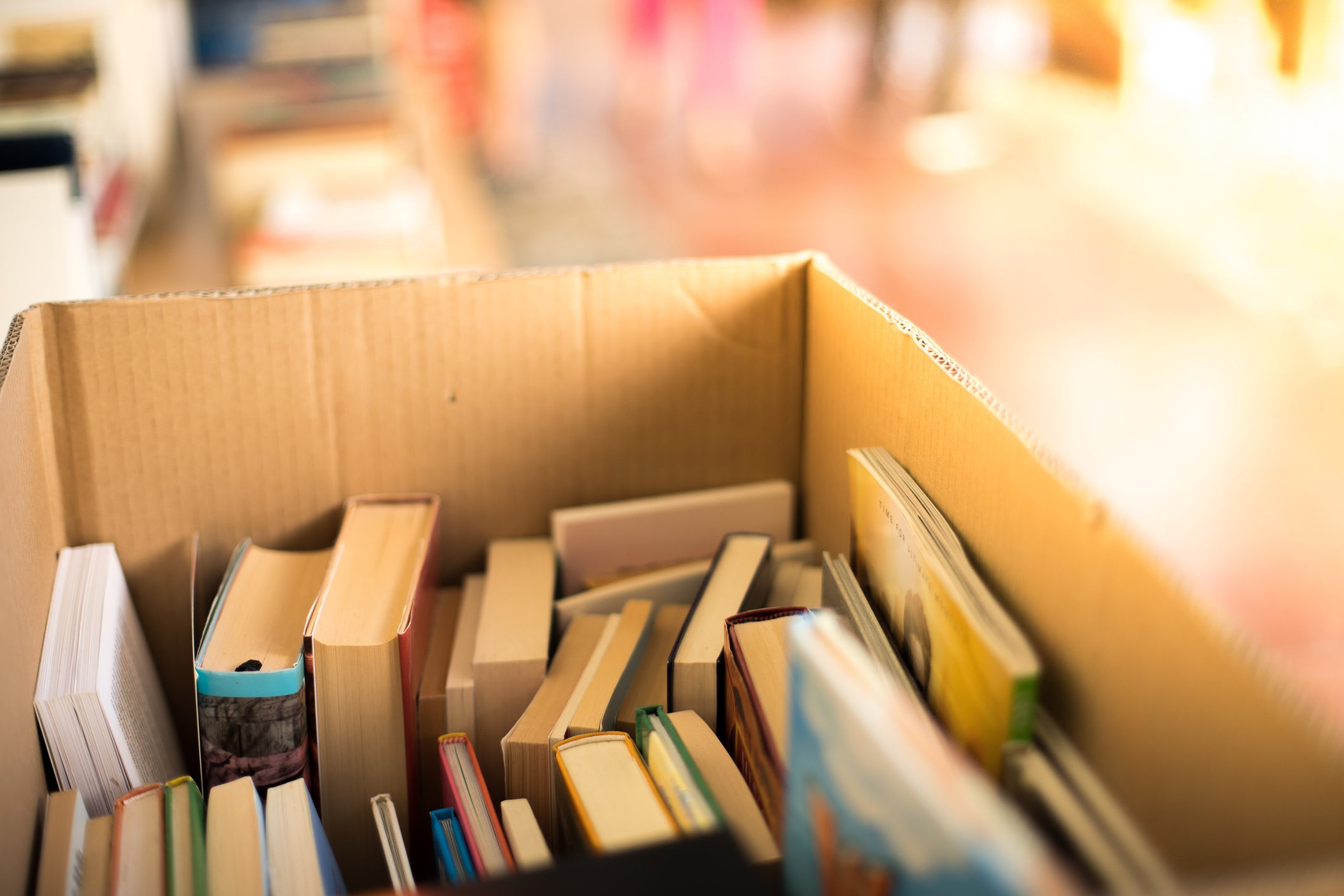

Finally, thanks to your merciless audit, there will be a “pending pile” of final rejects, and your principal discards will be boxed up, ready for their despatch into doom. Now, you discover the shocking crunch hidden within this traumatic process: how hard it is to dispose of old books in the 21st century.

Consider this paradox: in a golden age of reading (in many formats, analogue and digital, in countless global markets, not just in English but also in the 23 languages spoken by more than half of the world’s population), second-hand books occupy the limbo between discarded newsprint and the dusty relics of an overcrowded attic.

If they are no longer resaleable, what are you to do? Could you stomach a ride to the municipal dump as a pocket-Goebbels? Can you really dump your ex-library in a skip without the shameful feeling that you’ve just become an Ostrogoth?

When you venture into the used book market, such as it is today, you will find that the strongest interest will come from the remaining merchants who want potential pulp for wallpaper and toilet rolls. That foul-smelling second-hand bookshop in the seedy purlieus of some provincial town is a thing of the past. These days, Oxfam mostly says No Books. Many other charities are similarly book-averse. In extremis, Abe Books offers itself as a good deed in a world going to hell in a handcart.

In Shakespeare’s time, a well-read reader could load every volume from a treasured library – what used to be called “the canon” – onto a trusty wagon. Today, when everything’s available online and on demand, there’s no place for such carts.

There is World of Books (formerly Ziffit), a wonderful app that scans a book’s barcode and will buy good books for a few pence to a couple of pounds; it even picks them up from you. But the most modest library of old books has only the smallest resale value, unless they happen to be first editions inscribed with extravagant autograph dedications.

For instance, there’s a Mayfair dealer in rare editions whose Christmas catalogue has a first edition of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, published in 1998, marking the debut of an astonishing cultural phenomenon. Signed by the author, it’s advertised at £12,000. That is what they call publishing gold.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks