How Moomin creator Tove Jansson found her dark side illustrating Tolkien and Carroll

She thought Lewis Carroll was ‘pathological’. Her Gollum was so monstrous that JRR Tolkien amended his book’s text – but copies of Tove Jansson’s illustrated edition of ‘The Hobbit’ fly off shelves even though they remain in the original Finnish. Susie Mesure visits a new exhibition that shows how the brain behind the Moomins turned her vividly macabre eye to transform other classic books

In November 1960, Astrid Lindgren got in touch with Tove Jansson, the creator of the Moomins. Lindgren, who wrote the Swedish children’s classic Pippi Longstocking, was also a publisher – and she begged Jansson to turn her imagination to the works of JRR Tolkien. “Who will comfort Astrid if you don’t agree to the proposal I’m now going to make to you?” Lindgren wrote in a letter, riffing on the title of another of Jansson’s recent picture books, Who Will Comfort Toffle?

In the UK, as in her native Finland, Tove Jansson is, of course, best known for the Moomins, an adventurous family of fantastical creatures who live in a magical valley on the edge of a Finnish archipelago. A Moomin comic strip ran in London’s Evening News from 1954 until 1975, reaching millions of readers across the Commonwealth, and, more recently, the first new animation series about the Moomins for nearly three decades – Moominvalley – brought the white trolls to life for a new, younger generation. Fans range from devotees who grew up on books such as Finn Family Moomintroll or Comet in Moominland, to those with a penchant for collecting Moomin mugs, which Moomin Characters, the family-owned company that looks after Jansson’s legacy, still churns out year after year.

Less is known, however, about the success Jansson, a Finnish icon who died in 2001 aged 86, had illustrating the work of other writers, something a new exhibition in Paris is putting under the spotlight. Houses of Tove explores how Jansson was so much more than a comic strip creator, a job she came to loathe because it kept her from her true passions: painting and writing. The show includes a first edition of The Hobbit, or Bilbo – en hobbits äventyr, as it is known in Swedish, which Jansson jumped at the chance to illustrate for Lindgren. It also features a number of preparatory sketches she made for the commission, which were used in a 1973 Finnish translation: the first edition, featuring a wonderful red dragon hovering above a tiny army scaling jagged peaks, is on display.

The work Jansson did on Tolkien’s classic story reveals her tremendous energy and her perfectionist streak. She described her struggles in a letter to a friend, reprinted in Letters from Tove, a collection edited by her biographer Boel Westin and Helen Svensson and translated by Sarah Death. “I drew some of the smaller pictures 60-80 times before they started to ‘flow’. It’s damned depressing how one can get so stuck on something one is ‘expert’ at,” Jansson wrote in 1961.

Her persistence is to be applauded: the Finnish edition is a cult favourite among British Tolkien fans, who account for around one-third of all the copies of Hobbitti Eli Sinne Ja Takasin printed each year. Indeed, I bought a copy for my then 13-year-old son, who has read everything Moomin-related that Jansson wrote, as well as everything Tolkien, wrote several times over.

Hobbitti is one of the best-selling items at the Moomin Shop in north London, according to the shop’s founder Magnus Englund – despite costing £35 and being unintelligible to most people. “We’ve been really surprised how many we sell. We get Tolkien enthusiasts buying it from all over the world,” he adds.

Tolkien’s novels were favourites in the Jansson household when Tove was growing up, says Sophia Jansson, her niece and creative director at Moomin Characters. “The whole idea of the Hobbit travelling is a classic but it was something that appealed tremendously to the Janssons [who loved] adventures and quests. One of the first books my father [Tove’s brother, Lars] read to my sons was The Hobbit.”

I ask Westin to expand on Tolkien’s appeal to Jansson. The Swedish biographer says Jansson loved the “horror factor” in Tolkien’s plots because they reminded her of another favourite writer: Edgar Allan Poe. “[Jansson thought] Tolkien was even more gruesome than Poe,” Westin replies. Plus, Jansson was eager to draw the landscapes Tolkien described. We know this from a letter Jansson wrote to her partner, the painter Tuulikki Pietila, in which she describes how Tolkien’s scenery “is seductive in its macabre ferocity. Forests of living horror, coal-black rivers, moonlit moons with fiery wolves – a whole world of catastrophe I know I can respond to in pictures.”

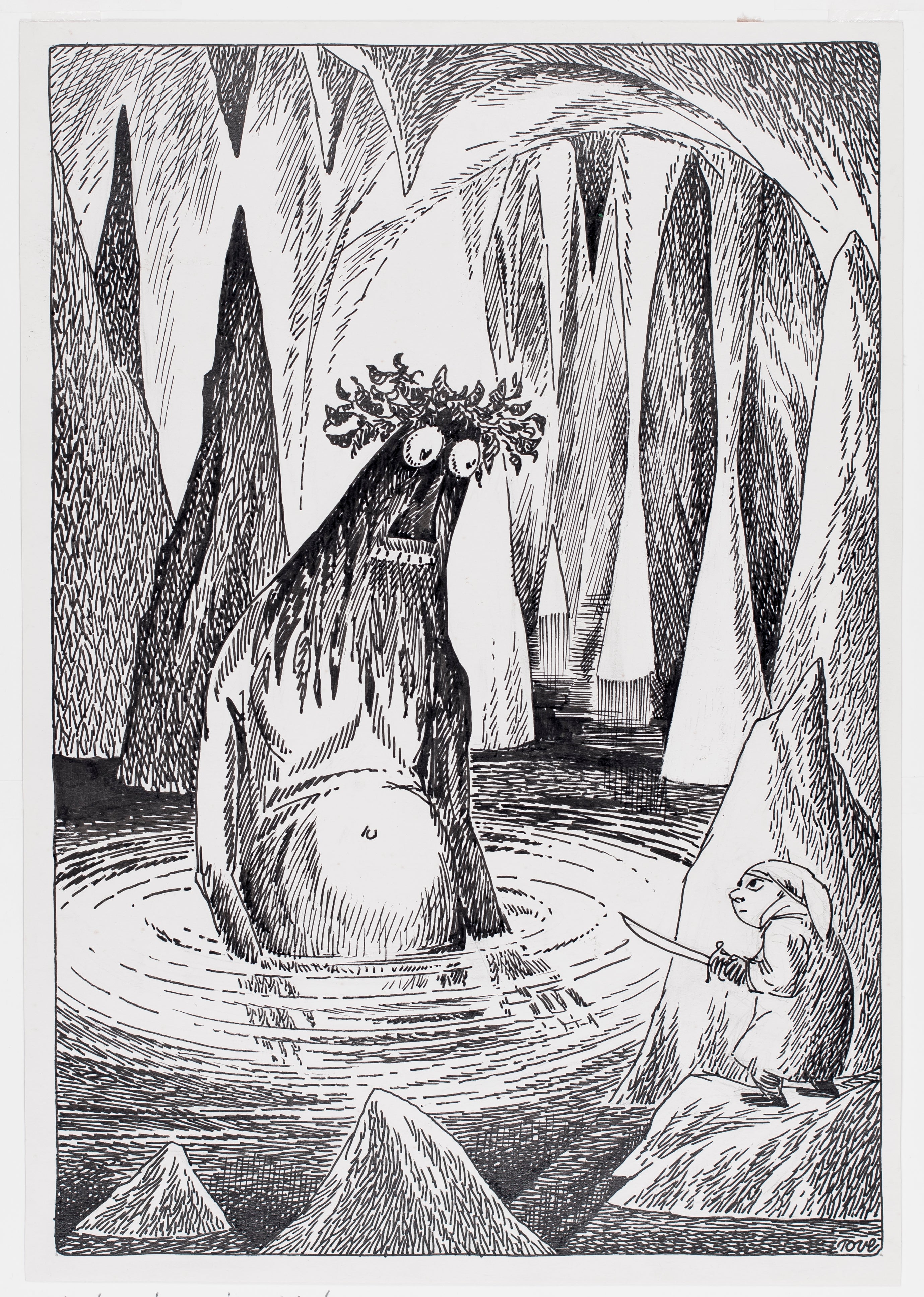

The irony is that, popular though Jansson’s illustrations are today, they were not well received on publication. Her depiction of Gollum caused particular grievance. As comics expert Paul Gravett pointed out in his recent book, Tove Jansson: The Illustrators: “Her Gollum towered monstrously large, to the surprise of Tolkien himself, who realised that he had never clarified Gollum’s size and so amended the second edition to describe him as ‘a small, slimy creature’.”

Before British Tolkien fans with a passion for Moomins get too excited, Jansson’s work is unlikely to appear alongside English text any time soon. “The Tolkien Estate has no plans to publish an English edition with the Jansson illustrations,” Cathleen Blackburn, the lawyer at Oxford-based Maier Blackburn who acts for the Tolkien Estate told me over email.

“It is a shame but we don’t want to rub anybody the wrong way and if they don’t want it, they don’t want it,” is Sophia Jansson’s response.

Tolkien wasn’t the only British author to get Tove Jansson’s artistic juices flowing. Enter Lewis Carroll, whose The Hunting of the Snark she illustrated in the late 1950s, before turning to Alice in Wonderland a few years later. Again, she was attracted by the undercurrents of fear. “Can I draw them in horror style? The way I saw them when I was little?” Jansson asked Ake Runnquist, her Swedish publisher and friend who was working on the translation, in 1965.

“Lewis Carroll was clearly completely pathological, there’s no way of making anything idyllic out of it. English people must be pretty dysmorphic, don’t you think, for all their cool understatement – or maybe because of it,” Jansson added.

Lewis Carroll was clearly completely pathological, there’s no way of making anything idyllic out of it

Commenting on the Carroll-Jansson relationship, Westin says: “She wanted to catch the surrealistic dimensions and to visualise some sort of pathological nightmare worthy of Hieronymus Bosch.”

James Williams, an expert in Victorian Literature at the University of York, points out how Carroll and Jansson shared a sense of the absurd that explains the bohemian Finnish artist’s attraction to the donnish Carroll, who lived his life according to strict sets of rules. “Both were also inquisitive and quizzical in similar ways. They both loved to make themselves good at a range of different things and shared a strong work ethic. ‘Work and love’ was her private motto. They were both workaholics,” he adds.

Williams notes how “glimpses of things on the periphery of Lewis Carroll’s vision catch Jansson’s attention. The hallway where Alice weeps an ocean of tears, for example, is ‘lit with a row of lamps hanging from the roof’ – the kind of throwaway detail in Alice that, even more than the trial scene, anticipates the nightmarish quality of Kafka’s The Trial. Tenniel [the prominent Punch cartoonist and best-known of the many Alice illustrators over the years] overlooked them entirely; but Jansson makes these lamps prominent and hypnotising, illuminating what she saw as the book’s sense of terror, and offering, at the same time, a ‘shiver of pleasure’.”

Given that Carroll’s estate is out of copyright, Moomin Characters is often asked to make Jansson’s Alice artwork into merchandise. “We are considering it,” says Sophia Jansson. For now, several pieces are on display in Paris. Curator Sini Rinne-Kanto says: “[Jansson’s work for Tolkien and Carroll] did not receive a great reception at the time of publication; readers already had their own images in their minds of these classics. This means that good quality first editions of these books are now both rare and very valuable. We wanted to include these sketches to show the breadth of Tove’s work and especially to highlight her work that she did as a freelancer illustrator, outside of the Moomins and her personal artistic practice.”

Visitors can also see a host of other paintings, illustrations, photographs, and Jansson memorabilia, from the plastic flower crown she used to wear each year on her birthday, to hand-drawn covers for the scores of cassette mix tapes she and her partner Pietila used to make each other. The exhibition, which was curated by The Community, a multidisciplinary art collective, in collaboration with the Tove Jansson Estate and Moomin Characters, also features work made by seven contemporary artists in response to Jansson.

One of the strongest pieces is Blue Hyacinth, a painting by Jansson made in 1939 in Brittany that captures a view from her window. “Looking at domestic spaces was very prevalent in her work,” adds Rinne-Kanto, something this delightful exhibition captures beautifully. From the Moominhouse, which anchored Moomin family life, to Jansson’s cabin on her beloved Klovharun island (“a rock in the middle of nowhere”, as Jansson described it) in the Pellinge archipelago, Houses of Tove is a visual love letter to those spaces as well as proof of a prolific life, well lived.

Houses of Tove is on now until 29 October at 8 Impasse de Mont-Louis, 75001 Paris, free entry; housesoftovejansson.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks