Moomins on the Riviera: How Tove Jansson's creations beguiled the planet

The Moomins hit the big screen this week, and their journey from comic strips to cinemas is the opposite of a Disney-fied fairytale, as Boyd Tonkin discovers

Beyond nostalgic veterans of old Fleet Street, not many readers will have a clear memory of the Evening News: the London afternoon daily that, in 1980, merged with its rival the Evening Standard. This week, though, the millions of fans who cherish one of the best-beloved of all fictional families have good reason to salute this defunct paper – a judgment I would defend even if I weren't sitting in the office that The Independent shares with the Evening News's heir.

By 1952, the Finnish artist and writer Tove Jansson had already published five books devoted to the Moomins. She first drew the rotund and enigmatic creatures as ghostly, even sinister, fairy-tale characters in the 1930s: scary beasts for a scary time. During the Second World War itself, her Moomin family shook off the darkness of the age to become a benign, freedom-loving and quietly eccentric antidote to the surrounding tragedies. Happy at home in Moomin Valley, they wanted nothing more than to escape the follies and disasters that beset them; to "live in peace, plant potatoes and dream".

British readers rapidly fell for the books after Finn Family Moonintroll appeared in translation from the Swedish in 1950 (the Janssons, a family of artists, belonged to Finland's Swedish-speaking minority). Then, in January 1952, Charles Sutton – head of syndication for Associated Newspapers – wrote to Tove. Shrewdly, he suggested a daily Moomins strip that would "not necessarily be aimed at children", since "we think these wonderful creatures could be used in comic strip form to satirise our so-called civilised lifestyle".

Launched with a promotional fanfare in September 1954, the Moomins strip took up residence in the Evening News until 1975. Jansson's contract insisted that the stories avoid party politics, unhappy endings and the royal family. Furthermore, as her biographer Tuula Karjalainen reports, "no character was to eat another, even if it wanted to". Tove wrote and drew all the strips, six times a week, until in 1959 this punishing schedule proved too much for her. The unlikely celebrity had left, she complained, "no time for painting, let alone books, friends or solitude". Lars Jansson, her brother and collaborator, then took over.

Thanks above all to the strip, syndicated worldwide, the Moomins beguiled the planet. Sophia Jansson – Tove's niece and Lars's daughter – is chair and artistic director of Oy Moomin Characters, the company that oversees the Moomin brands and protects her aunt's creations as they continue on their travels across media and merchandise, and an associate producer on the movie. She says that "the comic strips are where it all started. So I hope that the film, for all its brilliance, can be a path back to the original."

Adored literary characters can run into peril when producers snatch them off the page. Walt Disney's track-record of travesties hit a nadir with the Winnie the Pooh franchised movies, which in their coarseness and crudity betrayed the spirit of AA Milne's illustrator , E. H. Shepard. In contrast, Sophia Jansson and her team keep a vigilant eye on Moomin branding, not only in the media but on assorted items from mugs to sneakers.

The spin-offs began early. "Moomin Week" in London, with adverts on buses, TV appearances and models in department stores, coincided with the first strips. But Tove, followed by Lars and Sophia, managed to supervise the cross-platform progress of the family. And this dynastic continuity has helped to safeguard the Moomins from a Disneyfied fate. In the Sixties and Seventies, Tove authorised television animations in West Germany and Poland. But after an early, rogue Japanese anime version – in which an improbably violent Moominpappa thrashes poor Moomintroll – the estate got a grip. It ensured that a second adaptation in Japan stuck to the peaceable, humourous mood of the originals. That series sold around the world in the 1990s, and helped inaugurate a second Moomin boom.

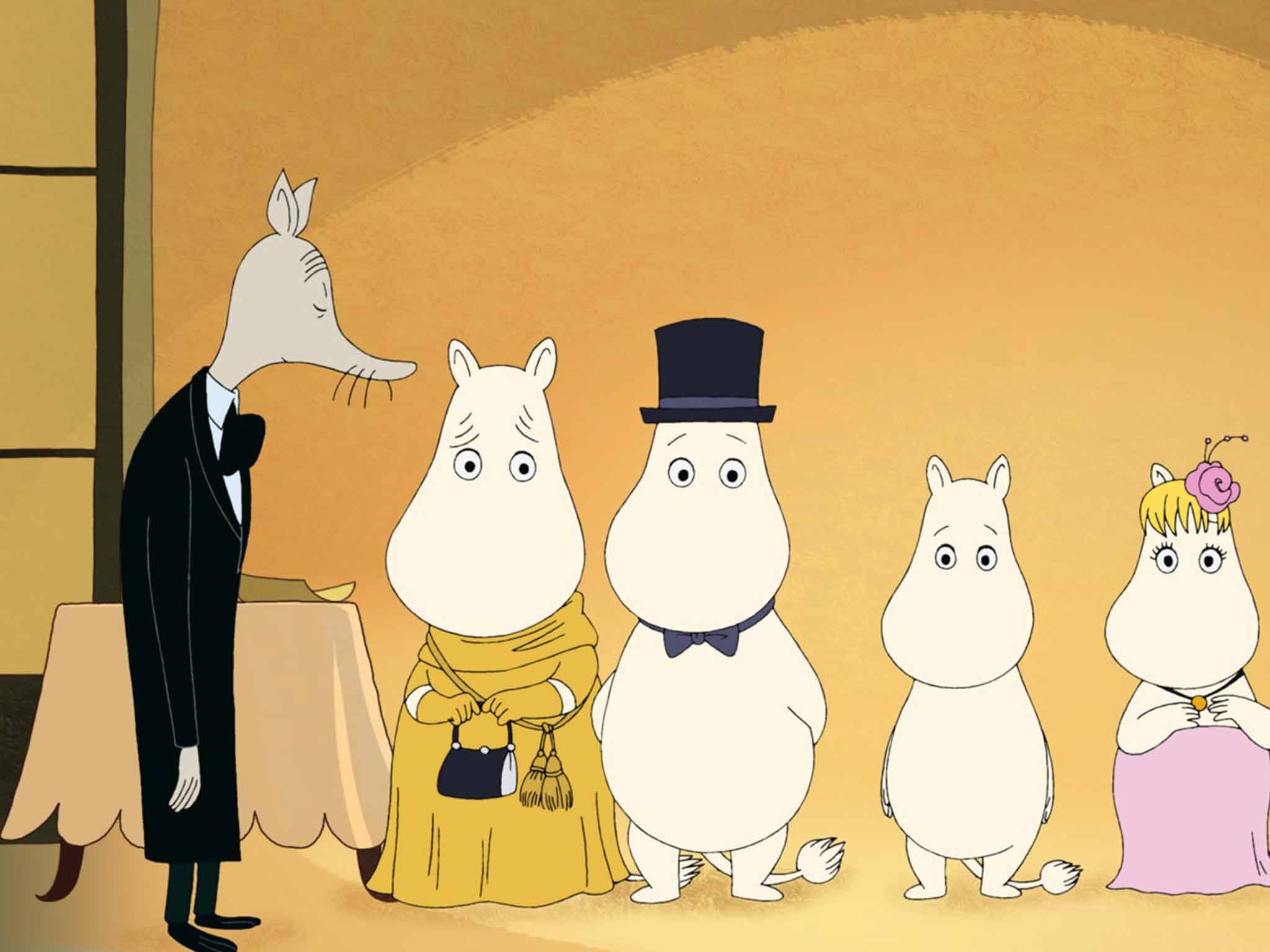

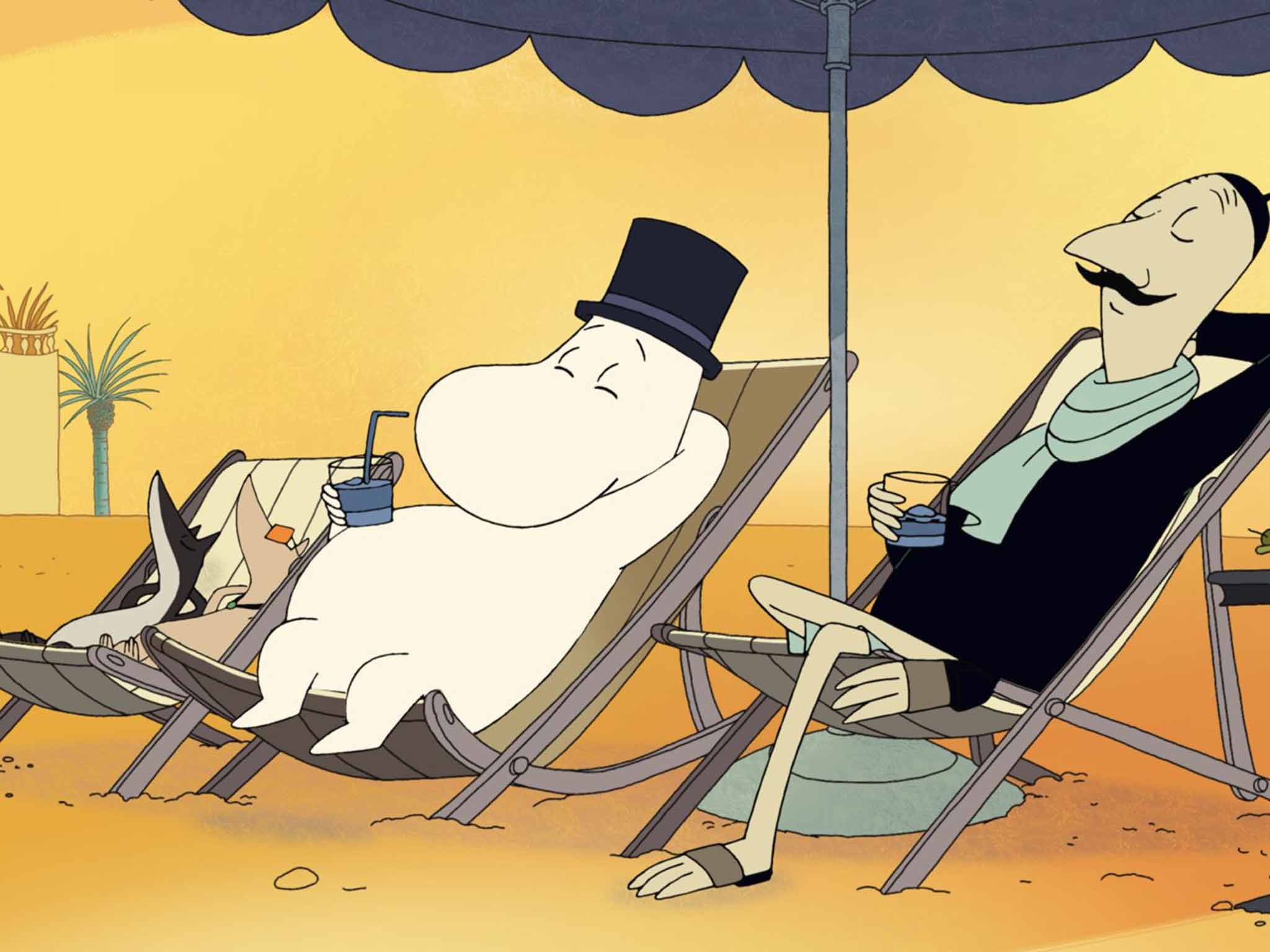

True to this tradition, Xavier Picard's film eschews CGI sorcery in favour of deadpan wit, gentle satire and benevolent silliness. In strip form, Moomins on the Riviera dates from 1955: the year, incidentally, when Tove met artist Tuulikki Pietila, the partner with whom she spent the next 46 years. Picard's film of the family's ill-starred adventure in the South of France preserves a defiantly flat, print-based style. Sophia recalls that previous bids for big-screen adaptations had wheeled out the animatronic heavy weapons. "We got lots of proposals for 3D films. They just didn't look right." Then Picard came along with his hand-crafted, low-tech vision. Sceptics scoffed, saying that "you can't do that, it's old-fashioned. Nobody makes films like that any more."

They do. They have. Sophia Jansson emphasises that the gleeful mockery of Cannes-style celebrity narcissism keeps faith with the original's adult edge while never alienating younger fans. "We tried to make it enjoyable for all ages," she says. "Tove's books are clearly meant for everyone." She also relishes the surreal strangeness of Picard's animated palette, with its lurid crimsons, turquoises and oranges. The director told her that the Moomins' spell in the south reminded him of "old postcards from the Riviera from the 1930s: very intense, warm colours". She loves the dream-like, almost psychedelic result: "Tove was an artist – she was very, very particular about colours."

The Moomin legacy and its careful oversight confirm that, just as the books and strips show, family matters. With the brand, as in the film, intimate low-key charm conquers flashy corporate pretension. Sophia remains thrilled that her aunt's sweetly philosophical tribe can still work their modest magic. "At Waterstones in Piccadilly, I was just amazed. In the children's books department, there was a whole shelf of her, right next to Paddington! It's really heart-warming."

'Moomins on the Riviera' opens on Friday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks