Philip Guston at Tate Modern review: An extraordinary, startling show full of moral disquiet

Could this be the most compelling exhibition of the year so far? Postponed after the death of George Floyd due to its use of Ku Klux Klan imagery, Tate’s retrospective of the American painter was worth the wait

Back in September 2020, directors at the Tate decided we wouldn’t see this retrospective of Philip Guston until 2024. After the murder of George Floyd, it was felt that the American painter’s cartoonish Klu Klux Klan imagery was too inflammatory for the highpoint of the Black Lives Matter moment. Thus Tate, along with the three major American galleries also hosting the exhibition, put the show on hold for two years. Now finally it opens at Tate Modern this week, and it’s a revelation.

Yet that original decision to postpone didn’t come without massive controversy. A letter signed by 2,000 artists, including many leading figures, condemned the museums’ lack of courage and failure to interpret the work or come to terms with their own “history of prejudice”. Yet in that charged atmosphere, the fact that Guston was a lifelong anti-racist and Jewish – therefore a target for America’s most notorious racist organisation himself – didn’t seem to count. Mindful of the fact that the statue of Bristol slave trader Edward Colston had only recently been consigned to the River Avon, and not wanting to provide even the slightest incitement for mobs to run amok through Tate Modern, the institution went ahead with the postponement.

The exhibition finally opened in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in May last year, without event, and is opening now in London, with little sign of trepidation on Tate’s part. So what’s changed? Well, everything and nothing. That moment of pandemic period high uncertainty, when the world appeared to be irrevocably changing, now feels a remote historical episode – with most things put back pretty much the way they were. Philip Guston’s paintings, meanwhile, particularly the supposedly controversial late works, seem more extraordinary than ever. They’re revealed in this startling show as the final flowering product of a career of constant shifting directions, mostly in response to political and moral rather than purely artistic imperatives.

Born Philip Goldstein in Montreal in 1913 to a family of working-class Jews who had fled persecution in Ukraine, Guston seems to have been inculcated into a state of heightened political awareness almost from the moment he could speak. His father hanged himself in the garden shed when Guston was 10, and while Guston’s own political activism was intermittent, matters of violence, cruelty and intimidation seem barely to have left his mind.

If you’re American you’re not going to find a more potent embodiment of bigotry, intolerance and murderous stupidity right in your domestic hearth than the KKK – who behind a mask of Christian respectability have carried out innumerable murders, particularly of African-American political activists. They even come with their own absurd but alarming imagery of white hoods and cross-burnings. During Guston’s childhood in Los Angeles, membership was at a high of between 2 and 5 million members, including both the city’s police chief and council president. Guston was, as he later wrote, “haunted [by the KKK] since I was a boy”. As young as 17 he was producing drawings of Klan lynchings in a monumental style that owed something to Renaissance painters such as Giotto and Piero della Francesca. A “portable fresco” of Klan violence produced in support of the Scottsboro Boys, a group of young Black men framed for rape, was destroyed by the LA police during a raid on a communist club in 1933. Guston, you feel, had earned a lifelong right to portray the Klan in any way he chose by the age of 20.

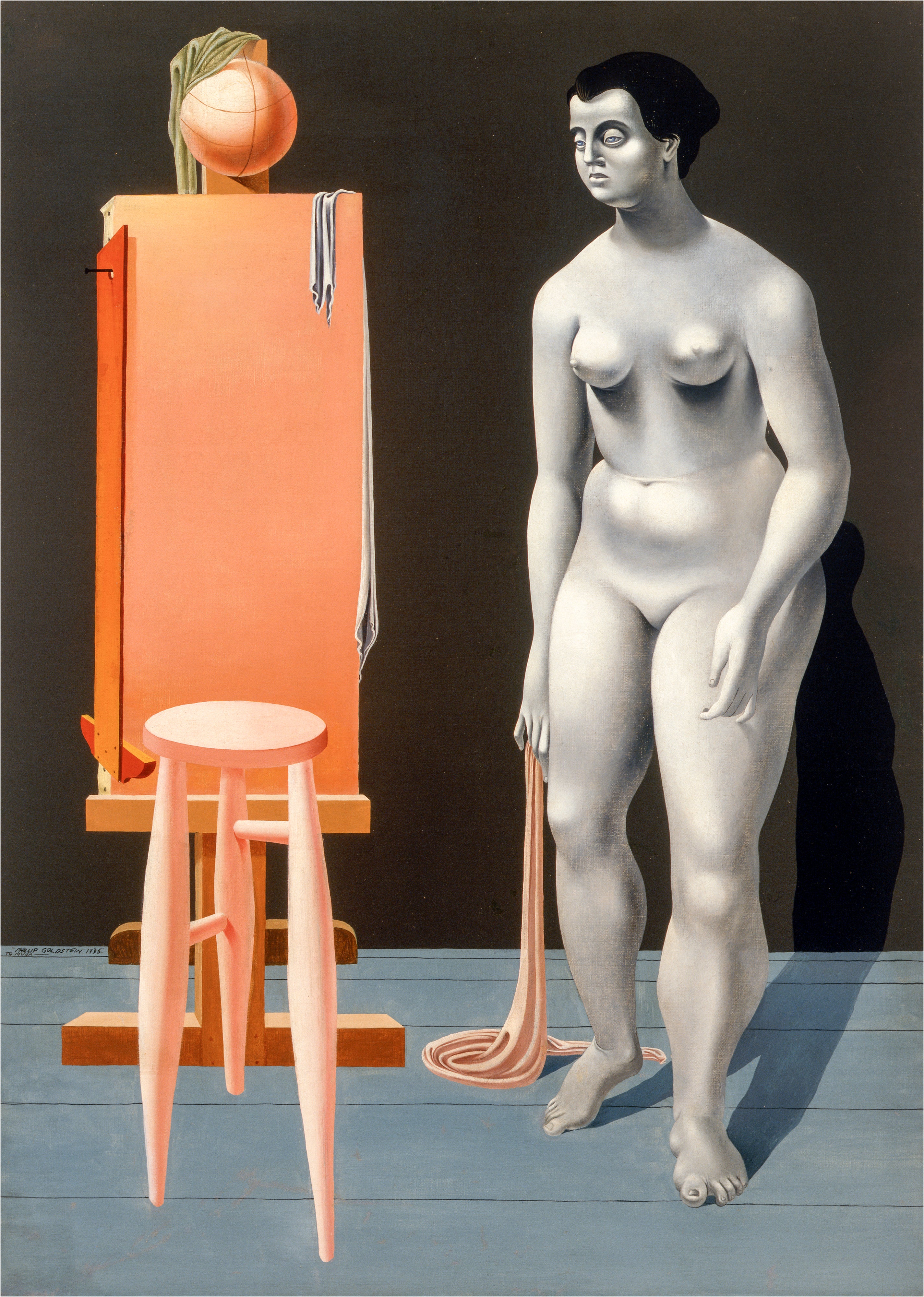

Like most American artists of his generation, Guston was powerfully impacted by Surrealism, evident in three extraordinary paintings that stand up remarkably well beside their evident European influences, Giorgio de Chirico and Max Ernst. Mother and Child (1930), with its smouldering fleshy Madonna figure, is an amazing achievement for a lad just out of his teens.

In 1934, Guston and friends Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner travelled to Mexico to create a colossal mural, with the support of the leading Mexican artist David Siqueiros, entitled The Struggle against Terrorism, depicting the “history of persecution”. Shown in a wall-filling video in its current somewhat battered state, it’s a highly impressive work filled with gigantic, tormented figures in a sort of Marxist-Renaissance style. Guston, meanwhile, can’t keep hooded, clearly Klan-referencing apparitions out of his section of the work.

The Porch and The Porch 2 (1946-7), brightly coloured and attractive paintings densely packed with overlapping figures and abstracted architectural elements, were, surprisingly, informed by his traumatised response to the revelations of the Holocaust, which left him feeling he “couldn’t continue figuration”.

Tasteful medium-scale abstract paintings in which the wall texts claim to detect traces of pointed hoods (I couldn’t see them) led to the Abstract Expressionist canvases for which Guston was for decades best known. Swarming backgrounds of pink- and blue-tinged brushstrokes are overlain with surging masses of primary colour: distinctive blues, reds and green that tend to remain constant in hue from painting to painting. Fable (1956-7) with its vigorous masses of freely applied black paint feels like a struggle between singing colour and stark monochrome. These are strong paintings that still look fresh 70 years on, though it’s easy to see why Guston was one of the most respected, but never quite one of the most loved, of the Abstract Expressionists; he deliberately avoids the grandstanding melodrama of Pollock and Rothko.

Indeed, it feels as though he’s barely got into his stride as a full-on abstractionist, before the figurative impulse starts reasserting itself. Clusters of dark grey marks on cloudy, fugitive backgrounds from the mid-Sixties were understood by him to represent heavily abstracted “heads”.

But it was the social and political turmoil of the late Sixties that prompted his urge to “un-numb” himself and return to “bearing witness” to his time – as he believed it was the responsibility of the artist to do – in overtly figurative imagery. With the horrors of the Vietnam war ever-present in the media, the protests of youth and violent reactions of the authorities, Guston found himself wondering “what kind of man am I… going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”

When the paintings he produced to “bear witness” were first exhibited in 1969 they produced horrified responses even in sympathetic friends. It’s impossible to look at City Limits (1969) with its three hooded Klansman crowded into a tiny car without giving vent to a nervous inner chuckle. Guston wanted to evoke what it would be like “to live close to evil”, even to “be evil” himself. The simplistic deadpan treatment of the bizarre image contrasts weirdly with the imposing near-Abstract Expressionist scale, and the sumptuous red tinging of the colour strongly recalls his own abstract painting. This isn’t an “easy” painting.

In The Studio (1969), a cigar-chomping, Klan-hooded painter with an immense red hand carefully paints another Klan-hooded figure by the light of a naked bulb. Clearly an ironic self-portrait, it embodies the dark comedy of the artistic condition in which the artist is condemned to keep portraying their own “evil”, while focussing simultaneously on the supposedly neutral “painterly values” – colour, composition, etc – that are their stock in trade.

Masses of cartoonish legs emanating from a gigantic mouth or entangled into a writhing mass in a painting called Monument (1976) may, the wall texts suggest, be a reference to the “piles of bodies and shoes (Guston) saw in images of the Holocaust”.

Yet his contemporaries were concerned less with the political resonances of these images than the conundrum of why one of America’s most distinguished painters had opted for this bizarre and lumpen figuration. In Painting, Smoking, Eating (1973) he portrays himself as a monstrous stubbled child with a single enormous eye smoking in bed with a plate of gigantic chips on his chest: hardly the most dignified image of an artist in old age.

There’s nothing that disconcerts people, particularly weighty art people, like not knowing what they are and aren’t supposed to take seriously in an artist’s work. And that really is the point of Guston’s late paintings. We can’t afford to take evil of the kind represented by the Klu Klux Klan entirely seriously. We can’t deem their absurd regalia and cross-burning “terrifying”, as they would like these things to be seen. And at the same time, we can’t afford not to take their threat utterly seriously.

It’s that sense of niggling moral disquiet expressed in images that have something of the toilet wall scrawling, something of the underground comic illustration and something of the old master fresco that makes this perhaps the most compelling exhibition of the year so far. Guston was more than worth the wait.

Tate Modern, until 25 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks