As vaginal mesh procedures are suspended, why did it take so long for women's pain to be taken seriously?

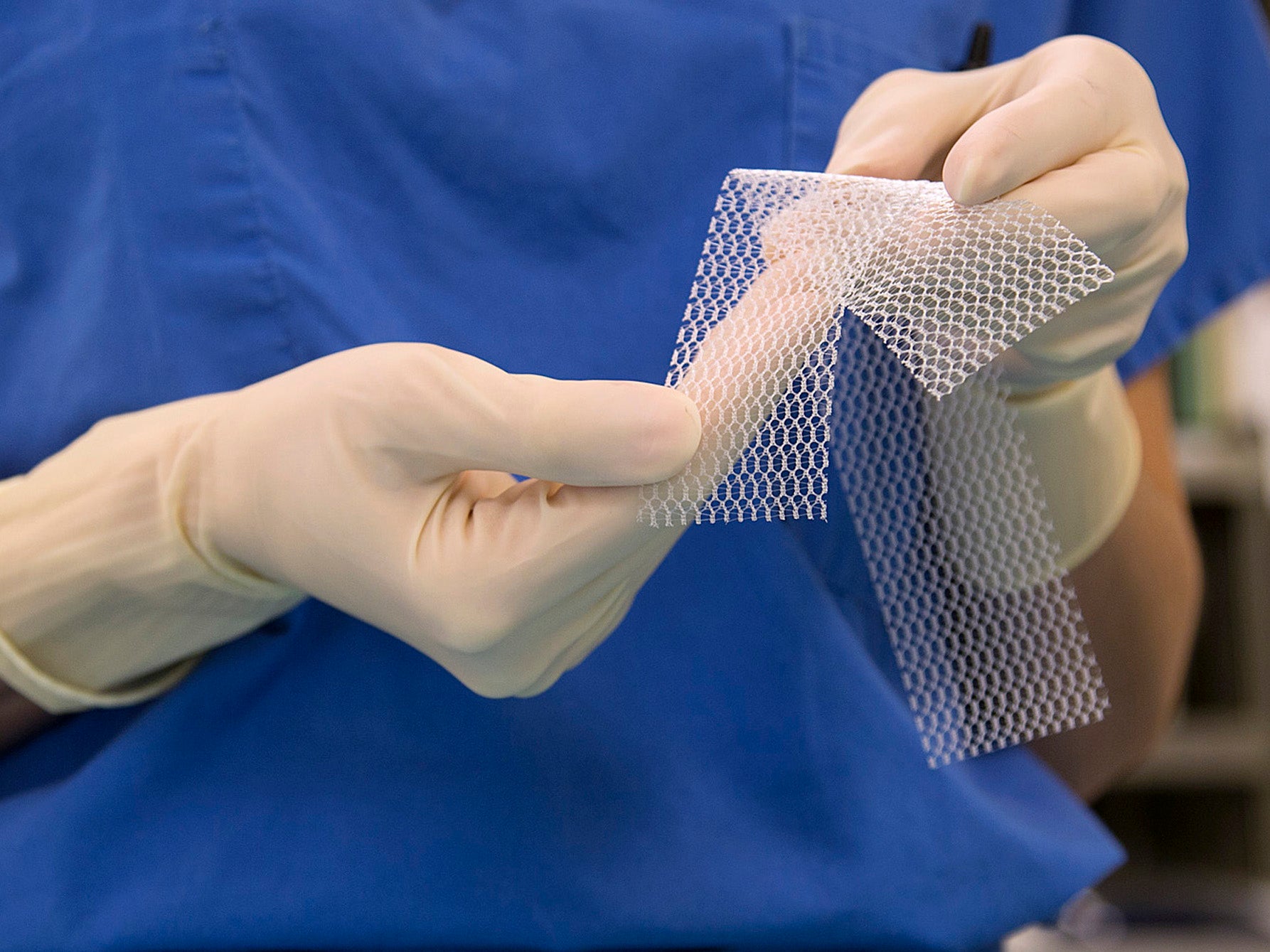

The insufficiently tested and poorly regulated plastic mesh devices have been shown to erode and disintegrate, slicing through organs and vaginal walls to cause paralysis, chronic pain, sepsis, loss of sex life and even organ failure

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“It’s the end of mesh,” said Labour MP Owen Smith on the Victoria Derbyshire show today. Well, not quite.

NHS England has accepted a recommendation to temporarily suspend vaginal mesh implants for the treatment of stress-urinary incontinence (SUI) until March 2019. It is hoped that Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland will follow suit. This joins last December’s recommendation from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), to ban vaginal mesh as a treatment for pelvic organ prolapse (POP).

It’s been hailed as a great victory by campaigners and the thousands of women affected by the devices, over what politicians have called “the biggest health scandal since thalidomide”. The insufficiently tested and poorly regulated plastic mesh devices have been shown to erode and disintegrate, slicing through organs and vaginal walls to cause paralysis, chronic pain, sepsis, loss of sex life and even organ failure.

In December, New Zealand became the first country to ban all vaginal mesh procedures, after Australia banned procedures to treat prolapse. And Chrissy Brajcic, an anti-mesh campaigner from Ontario, Canada, became the first woman known to die from complications relating to a mesh device.

In January, the Department of Health and Social Care committed to reviewing every vaginal mesh implant case since 2005 to determine the true extent of complications.

So we’re definitely getting somewhere. Like strides made in the treatment and awareness of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis and vaginosis, women’s pain is finally being acknowledged and investigated, empowered by a collective refusal to suffer in silence any longer.

When campaigner and mesh victim Kath Sansom first set up the Sling The Mesh Facebook group, there were only a handful of members. Now there are more than 6,000: victims, family members and doctors, led by a core group of indefatigable women.

Members share tips and information, compare symptoms and treatment, and participate in collective activism: writing, tweeting, attending parliamentary debates and lobbying for results. The group also functions as an emotional support network: members comfort each other when in pain, when demoralised and even when suicidal.

Without this incredible network of mutual education and empathy, I doubt the lid would ever have been blown off this scandal. Every step taken against mesh is a testament to their resilience.

I look back to the women’s health movement of the 1960s and the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective of the 1960s and 1970s, which rose out of a context of stigma, ignorance, and Freudian theories of frigidity and hysteria.

Women felt their pain was ignored and dismissed by a patronising medical profession, suffering “pseudoradical infantilism”, in Betty Friedan’s words. Those women began to collectivise and self-educate, empowering each other to gain autonomy over their own bodies and challenge doctors, culminating in the seminal work Our Bodies, Ourselves.

Considering what those women did, starting with just a few hand-distributed leaflets, imagine what they might have done with Twitter.

This is what female-led activism can lead to: results. They made enough of a “fuss” that they couldn’t be dismissed any more.

But they shouldn’t have had to. I’m disheartened at the slow rate of progress between then and now, and the level of noise that women still need to make before anybody listens. Reading the stories on the Facebook group is heartbreaking: women still dismissed, women still ignored, women still sneered at and patronised. I wonder what the women of the Seventies would make of how far we haven’t come.

So the news that procedures have been suspended is a great victory, but it’s only a start. The All-Party Parliamentary Group on Surgical Mesh Implants, founded by Owen Smith, is still calling for a full investigation and retrospective audit of mesh surgery. This is absolutely vital in order to establish the true rate of complications.

Mesh used to treat rectal and abdominal prolapse, as well as to repair hernia in men and women, should also be suspended pending full investigation. All planned mesh sling operations in private hospitals must be cancelled, and doctors must be trained in the (already existing) alternative, safer procedures.

What’s next is compensation, and support for the hundreds of thousands of women already in litigation in the UK and US. No amount of money can repair bodies, broken families or bring the dead back to life – but it can offer quality of life, and in many cases help pay for the extensive treatments and repair surgeries necessary to survive.

Compensation is more than money: it’s priceless. It’s public vindication that someone should have listened to you and taken you seriously, and that someone will be held to account.

Speaking of money, we need to follow it. The medical device industry is a business like any other, and people have made a (figurative) killing on pushing these devices, that were known full well to be unsafe and unregulated.

There has been evidence of cover-up, corruption and conflicts of interest in this scandal, all allowed by a criminally negligent medical device regulatory system and facilitated by our chronically underfunded health system. We need urgent reform, and we need justice for the unknown number of innocent victims that have suffered and died already – and many still might.

For Chrissy Brajcic and the others, the fight is over. But for the rest of us, it’s only just begun.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments