With her first Budget, the chancellor must make the pips squeak – but how?

It will take more than jacking up capital gains tax to plug the chancellor’s £22bn black hole, warns James Moore – even just tinkering with it could have an unintended consequence…

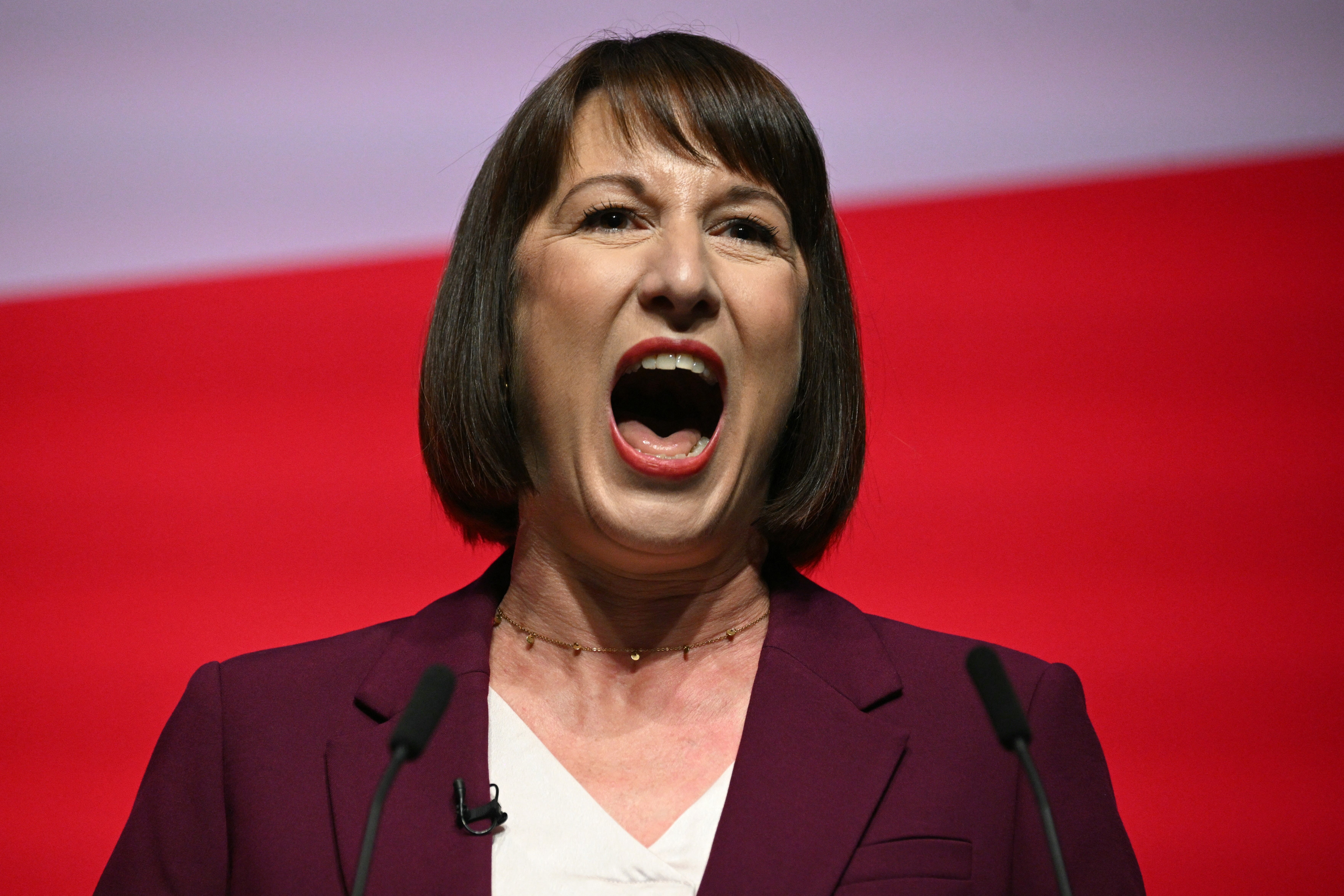

Is the government planning a capital gains tax raid? The possibility that, in her first Budget later this month, chancellor Rachel Reeves will push the rates into the stratosphere has created quite the tizzy – and prompted fierce government denials.

In advance of 30 October, we’re already seeing more leaks than Thames Water in a hot summer. The fuss over CGT has been caused by reports that the chancellor is considering pushing it up to as much as 39 per cent for higher-rate payers.

While an increase to that level has been pooh-poohed by the government, that doesn’t mean some sort of rise is off the table. Au contraire. And it could be quite a biggie.

Why is this a problem? Before we get to that, it makes sense to run through how this tax – which only a minority of Britons will ever encounter – works.

CGT is paid on any profits made by selling assets over and above a threshold of £3,000 (this year). Think second homes, stocks and shares, even art.

How much you pay depends on what you’re selling and what your tax rate is. Basic-rate income taxpayers are supposed to surrender 10 per cent on gains from most assets, 18 per cent on residential property such as a holiday home (your primary residence is exempt).

Higher-rate payers, which means anyone earning over £50,271, pay 20 per cent on most assets, 24 per cent (from 6 April 2024) on second (or third, or fourth) homes, and 28 per cent on carried interest, a reward linked to performance paid to certain investment managers. This also includes those on the 45 per cent rate which applies to income above £125,000. The Office for Budgetary Responsibility (OBR) says that around 350,000 people pony up in any given year.

As you can see, the difference between income tax rates and CGT rates is stark. Allowances and reliefs can further lower the latter. All this explains why top earners are very fond of things like “carried interest”, which is a share of the profits from a private equity, venture capital or hedge fund above a certain level.

It is pretty easy to see why raising CGT looks like a winner for Reeves: it is only paid by people with what Keir Starmer described as “the broadest shoulders” in his Rose Garden speech at the end of August. So the relatively and the very wealthy.

Here’s the problem: people with lots of money don’t tend to be overly fond of handing it over to the taxman, or anyone else for that matter. And the more money you have, the easier it is to move. CGT payers are the sort of people who can afford the services of advisors who can help them with the complex nitty-gritty of minimising their bills. Now would certainly be a fine time to sell a second home if that was in your thinking.

Some have argued that CGT should be equalised with income tax, albeit with an investment allowance so as not to deter people from engaging in something the UK badly needs more of.

The latest official figures show that the economy returned to growth in August – expanding by 0.2 per cent. Cue sighs of relief in No 11. But that doesn’t make it an express train or anything like it. It is more like one of those old branch-line locomotives that’s started slowly rumbling down the track after a stop at the station in a small town. Investment is badly needed.

The problem with squeezing those at the top until “the pips squeak”, in the words of a former Labour chancellor (Denis Healey, who was actually talking about property speculators) is that while it looks tempting and would probably prove popular with voters, there is a point at which it becomes counter-productive. The pips stop squeaking. They jump on a plane, and you end up raising less money than you would have by keeping the tax at a lower rate. Reeves certainly does not want to risk potential investors rushing for the exits.

I would still expect an increase, but nothing like to 39 per cent. Second homes may be a particular target – it was former chancellor Jeremy Hunt who controversially reduced the CGT on those for higher rate payers from 28 to 24 per cent. Odds on that will be going back up, and perhaps to a higher rate, given Britain’s housing crisis.

However, that won’t help her much. The OBR expects CGT to raise £15.2bn for Reeves in the current tax year. So even were she to double all the rates, and even if the pips all stayed put after their squeaking, it still wouldn’t generate nearly enough in terms of revenue to plug her £22bn black hole. Were she to just sharply increase the rate of CGT on second home sales, it would represent just a small drop in a big ocean.

All this comes before we get to the minor revolt in the bond markets, which are worried about how much she plans to borrow to fund public investment. Government borrowing has suddenly got more expensive too. No one ever said this was going to be easy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks