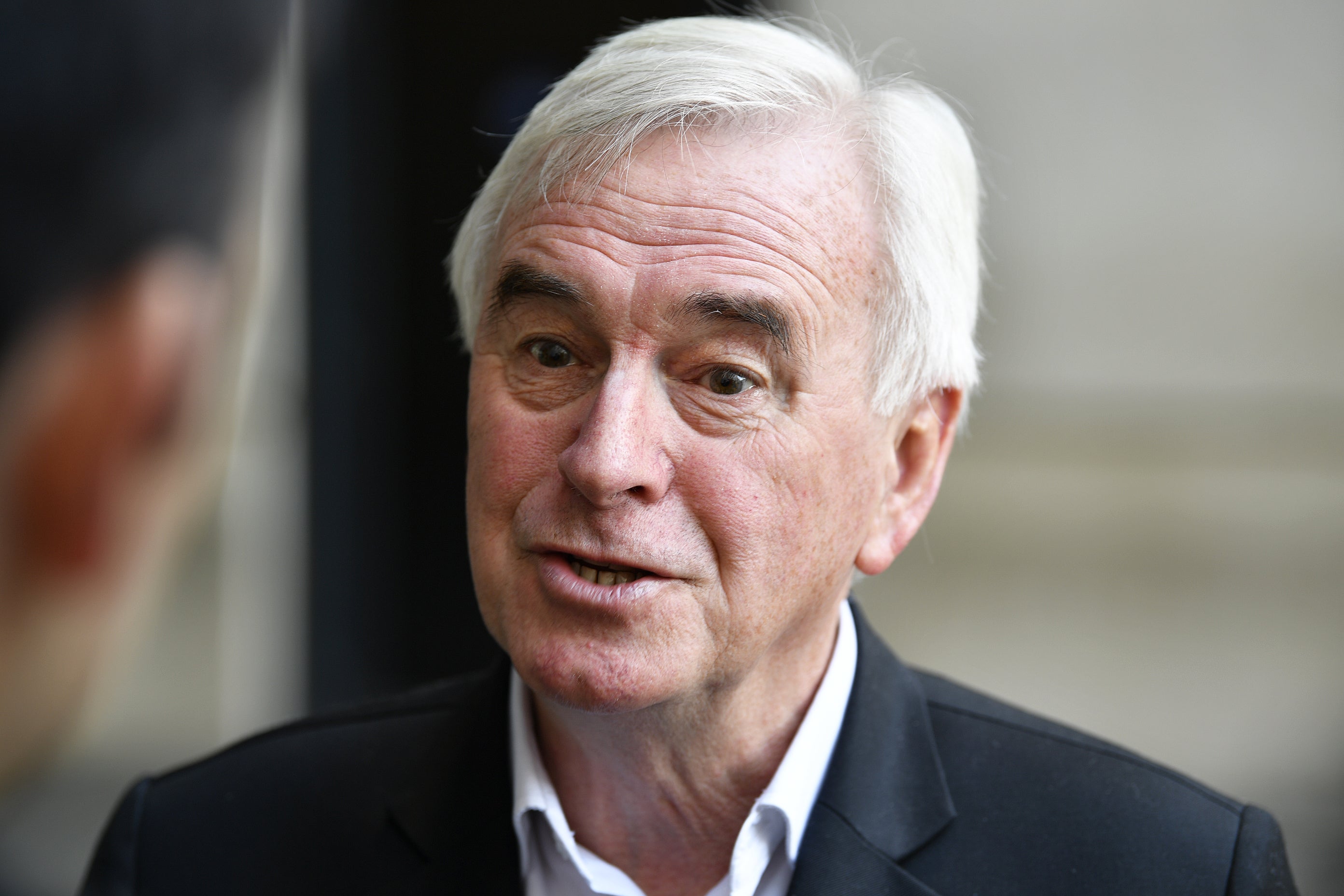

Ouch! John McDonnell feels the sting of firm government

Keir Starmer and his chief whip have been brutal in their punishment of the Labour MPs who voted against the party line on the two-child benefit cap – brooking no dissent is a lesson learnt the hard way during the Tony Blair years, says John Rentoul

Nineteen days after Labour was elected with a majority of 174, Keir Starmer cut his majority to 160 by suspending seven of his MPs. John McDonnell, the former shadow chancellor, was one of the seven expelled from the parliamentary Labour Party for six months for voting against the government.

They protest that they were voting to cut child poverty, by supporting a Scottish National Party amendment to the King’s Speech that called for the two-child limit on benefits to be lifted. They say that Labour wants to lift the limit but cannot afford to do so yet, so this is only an argument about timing.

On the other hand, Alan Campbell, Labour’s chief whip, says party rules do not entitle them to “vote contrary to a decision of the cabinet”. He and Starmer were plainly keen to strike, and to strike hard and early, to deter further rebellions.

It seems that McDonnell and his six comrades miscalculated. They thought that if there were a large number of rebels, it would be impossible for the government to discipline them. Tony Blair, for example, took no action against the 47 Labour MPs who voted against a cut in lone-parent benefit in December 1997, seven months after his landslide win.

But Campbell persuaded enough of his flock that voting against the King’s Speech would be a serious act of disloyalty. Historians point out that 45 of Clement Attlee’s MPs voted for an amendment to his King’s Speech in 1946, on the issue of conscription – but Campbell is right: it is unusual for MPs to vote against their own party’s programme for government.

In the end, only seven voted against: Apsana Begum, Richard Burgon, Ian Byrne, Imran Hussain, Rebecca Long-Bailey, McDonnell and Zarah Sultana. They are all members of the Socialist Campaign Group, and those who do Starmer’s organising would be happy for them never to return. I assume that is Starmer’s view as well, although it hasn’t always been.

Two MPs outside the Campaign Group threatened to rebel: Rosie Duffield and Emma Lewell-Buck, both of whom signed a Labour amendment to the King’s Speech that wasn’t selected for a vote. Duffield abstained on the SNP amendment, and Lewell-Buck voted with the government. That made it easier for Starmer to take a hard line.

There is some unhappiness among a wider group of Labour MPs at the severity of the response. They did not like a “government source” describing the incipient rebellion as “a virility test for No 10” to Alex Wickham of Bloomberg last weekend. This echoed the “machismo” of Blair and Gordon Brown in dealing with the lone-parent benefit rebellion in 1997, according to Philip Cowley, the historian of parliamentary rebellions. Blair thought giving way on the issue would “appear weak”, while Brown was said to believe that potential rebels “needed to learn a lesson sharp and hard” – before he was taken by surprise by the number of rebels and was urged to retreat.

By forcing the two-child limit issue early, it may be that Starmer and Campbell have succeeded where Blair and Brown failed – keeping the rebellion small enough that it can be dealt with brutally as an example to others tempted to vote against the government.

It is true that some Labour MPs are uneasy about this punitive response, although it must be said that many others are gleeful at the tactical ineptitude that has shrunk the Campaign Group’s already much-diminished influence. It is surprising to remember that its adherents led the Labour Party only five years ago – and that Long-Bailey was its candidate for the leadership against Starmer.

McDonnell, in particular, has always warned his allies not to give the leadership excuses to purge them – but now he, too, has been exiled.

Cowley says the “heavy-handed” discipline is a win for the government in the short term, but “in the medium term, it guarantees that the next rebellion will be big – big enough that you can’t suspend them because there will be too many – and then what do you do?”

He says: “I can see why the government wants backbench discipline, why it wants to be seen to impose discipline, and why, after the last few years, it feels the need to try to appear different. I am just not sure it will work.”

Meanwhile, the problem of children in poverty because parents on universal credit have three or more children continues to grow.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments