How George Osborne exploited our psychological biases to secure his cuts

The Chancellor seems to be calculating that the pain of future forgone gains will be less politically toxic than immediate cash losses.

Imagine you were offered a bet with a 50/50 chance that you could lose £10. What possible monetary win would induce you to accept the bet? Is it more than £10? In that case, you’re loss averse.

Is it significantly more than £10? £20? £30? Maybe even £100? The higher the potential winnings you’d require to take the bet, the more loss averse you are.

Now imagine the potential loss was not £10, but £100. How much would you now need to have a chance of winning before you’d take the bet?

Researchers who have studied how ordinary people respond to these types of hypothetical questions have reached the conclusion that loss aversion is hard-wired into our brains. It’s an instinctive response, rather than a calculated reaction. If people’s minds worked in the economically “rational” way assumed in a lot of economic models, people would take these bets (at least at relatively low sums) so long as the potential winnings only marginally outstripped the potential losses. But in practice, when we’re faced with a financial decision, the potential losses seem to loom much larger in our minds than the potential gains. And this psychological loss-aversion effect has an impact on the choices we make in a wide range of contexts.

Researchers have also found that people do not treat possible forgone gains resulting from a decision in the same way as equivalent potential out-of-pocket losses from that same decision. The forgone gains are much less psychologically painful to contemplate than the losses. Indeed, the gains are sometimes ignored altogether.

There was an apparent attempt to harness this particular psychological bias in George Osborne’s Autumn Statement. Of course the Chancellor was forced into a memorable U-turn on his wildly unpopular tax credit cuts. Millions of poor working families will now not see their benefits cut in cash terms next April. Yet the Chancellor still gets virtually all his previously targeted savings from the welfare bill by 2020.

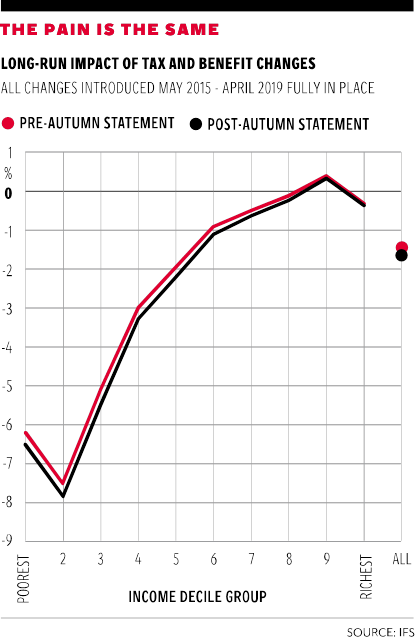

How? Because the working age welfare system will still become much less generous in five years’ time. As research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies and the Resolution Foundation has shown, the typical low-income working family in 2020 will be hit just as hard as they were going to be before the Autumn Statement U-turn. The Chancellor seems to be calculating that the pain of future forgone gains will be less politically toxic than immediate cash losses.

He’s probably correct in his calculation. Mr Osborne’s July Budget proposed to save £4bn a year by 2020 by freezing all working age benefits in cash terms for the next four years, meaning a deep cut after inflation for recipients. And that was actually a bigger saving than the one generated from the cuts to tax credits. But unlike the tax credit cuts, the benefit freeze prompted no outcry. Why? Because the immediate cash losses loomed far larger than the forgone gains of benefits rising in line with inflation.

Experiments by Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch and Richard Thaler also suggest that this stealth approach fits with people’s sense of fairness. They found that in a time of recession and high unemployment most people they surveyed thought a hypothetical company that cut pay in cash terms was acting unfairly, while one that merely raised it by less than inflation was behaving fairly.

There was another exploitation of our psychological biases in the Autumn Statement. The Chancellor announced an increase in stamp duty for people buying residential properties to let. That underscored the fact that the Chancellor remains wedded to the stamp duty tax, despite pressure from public finance experts to shift to a more progressive and efficient annual property tax (perhaps an overhauled council tax).

But Mr Osborne, like all his recent predecessors, realises that stamp duty, for all its deficiencies, tends to be less resented as a form of taxing property. Why? Because of “anchoring”. When people buy a house they are mentally prepared to part with a huge sum, usually far bigger than any other transaction they will make in their lives. The additional stamp duty payable to the Treasury on top of this massive sum, large though it is, seems less offensive. People resent it less than they would if the tax were collected annually in the form of a property tax – even if, for most, it would actually make little difference over the longer term. Sticking with stamp duty is the path of least resistance.

The Government has a Behavioural Insights Team (or "Nudge Unit") whose objective is to exploit the public’s psychological biases to push progressive policies, such as getting us to save more for retirement and helping us make “better choices”, perhaps by counteracting the negative impact of loss aversion. But, as we’ve seen, the Chancellor is not above exploiting our biases in a cynical fashion too.

In fairness to Mr Osborne, he has been made to suffer from these psychological biases too. In his 2012 “ominshambles” Budget, the Chancellor, quite sensibly, tried to eliminate the lower rate of VAT payable on hot takeaway food. It was dubbed the “pasty tax” by the press and politicians, because the price of hot pasties from bakeries would rise. The losers, such as the Cornish Pasty Association, complained noisily. But the winners, fast-food joints who don’t benefit from the lower VAT rate, were silent. Why? Probably because their hit was a forgone gain, rather than an out-of-pocket loss. Mr Osborne was eventually forced to scrap the pasty tax.

Local governments are up against loss aversion too. Why are so few houses built in Britain? One of the reasons is that groups of householders lobby councils hard not to grant approval to proposed new local developments in the belief that they would bring house prices down, reducing the value of their main asset. And they might – but that’s a benefit to younger people looking to buy. But the loss of the local first-time buyer is a forgone gain in the form of lower prices of the houses they might buy, rather than a fall in the value of an asset they already own. They thus tend to make less of a noise than the “nimbies”. They should make more noise. Loss aversion might be hard-wired into our brains – but we’d be better off if we attempted to override it from time to time.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks