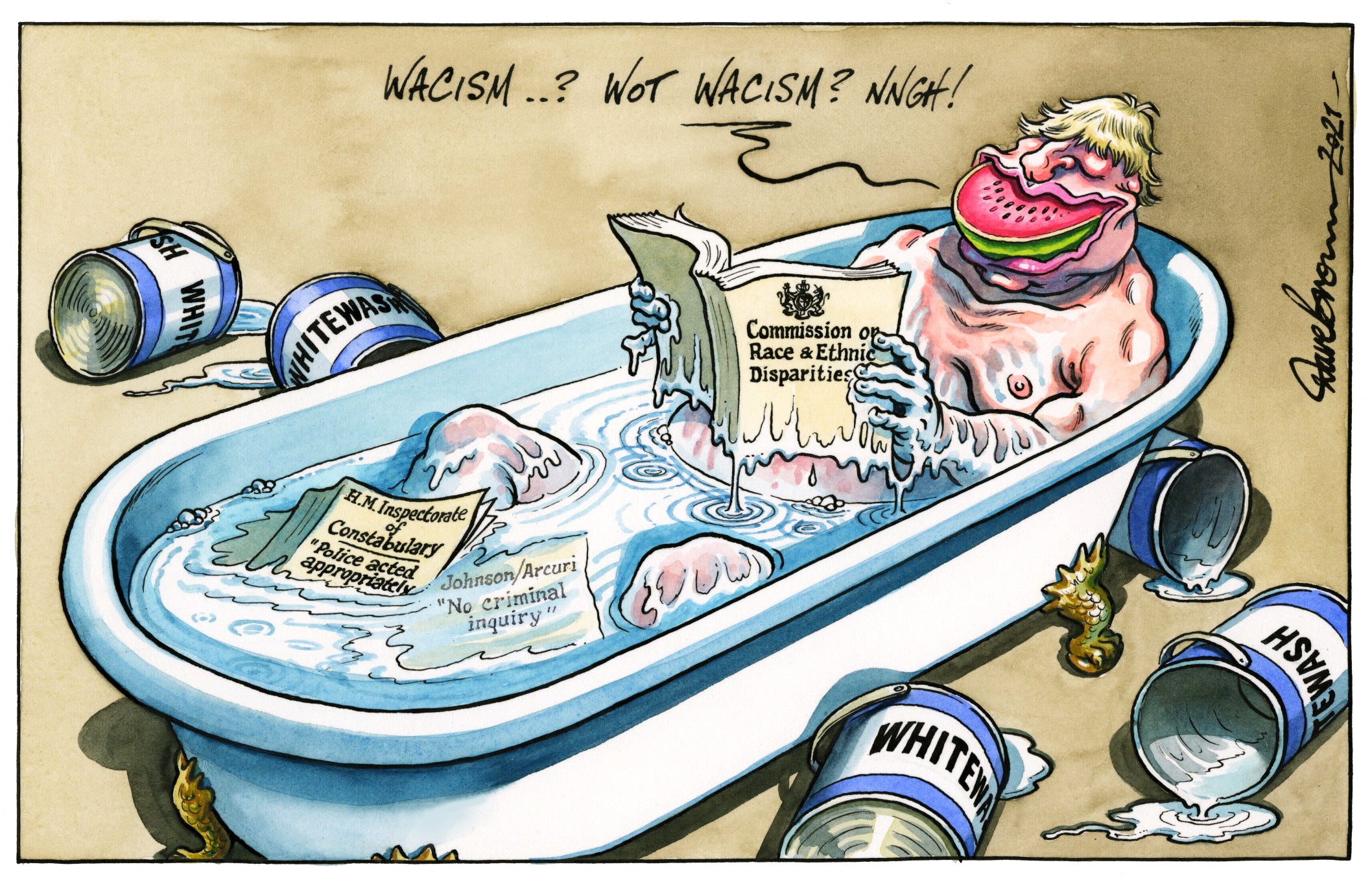

The Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities is an exercise in gaslighting

Editorial: This report will be disregarded and forgotten, and rightly so – it was produced by a committee inclined to think that if we all stopped going on about racism it would go away

At best, the report of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities is well-intentioned but self-satisfied, complacent and preordained. At worst, it is a deliberate and cynical exercise in what we have now come to call “gaslighting”.

Born out of a need to say or do something, anything, to respond to the Black Lives Matter protests last year – an explosion of pent-up frustration towards the racial injustices that still permeate British society – it has ended up, sotto voce, concluding that it is white working-class lives as much as anyone’s that are being undervalued and blighted by inequalities.

The whole BLM phenomenon, we are invited to believe, was based on a misreading of survey statistics. It is absurd.

It is hard to look on the commission’s work and avoid the obvious conclusion, predicted at the time it was set up, that Downing Street picked people to serve on it who could be relied upon to maintain the false narrative on race and equality that has been established by Boris Johnson and advisers such as Munira Mirza over many years. It is no accident that the report reads like a very long version of the kind of column Ms Mirza or Mr Johnson used to write.

In broad terms, the Johnson-Mirza worldview was, and is always going to be, that racism is less pernicious than it once was, that opportunities exist for people of all backgrounds to do well if they are industrious and grab them, that concepts such as “institutional racism” weaponise the issue politically, and that the proposition that people from ethnic minorities are discriminated against unfairly prevents them, perversely, from reaching their potential, by infantilising them.

Read more:

Or, in the words of the prime minister: “What I really want to do as prime minister is change the narrative, so we stop the sense of victimisation and discrimination.” Ms Mirza, a working-class Muslim woman, agrees with him.

The problem, of course, is that Ms Mirza’s experience is unusual, rather than emblematic and typical; and is not reflected in the life experiences of many other people of colour, no less ambitious or assiduous than her. When the commission called for evidence, it did not go out of its way to hear the life stories of people who did not end up agreeing with her that racism is “a perception more than a reality”.

Indeed there seems to be little account taken of the lived experiences of people of colour in general. The chair of the commission (a post wisely abandoned by Trevor Phillips), dismissed such evidence as “anecdotal”, as if it were unreal as well as statistically insignificant. Overly reliant on quantitative data, not all of it universally accepted or the last word in thoroughness, the report is light on qualitative evidence. It is that evidence, that experience, that gave rise to so much anger last year, understandably. Hence the gaslighting.

If Britain is to be declared a beacon to the world and to be free of “institutional racism”, it will need a more thorough, balanced and representative job than this. Compare its 258 pages of preordained content with the vast amount of evidence openly taken by the Macpherson Inquiry more than 20 years ago – which was an investigation into only one public body, the Metropolitan Police, where such attitudes were exposed after the murder of Stephen Lawrence. By comparison with the Macpherson Report, the commission’s report is necessarily superficial, and was intended to be.

“Bame” may be an overused term, as the commission concludes, and unhelpful in some analytical contexts. It is true that different ethnic minorities – not just classified very broadly by race – see outcomes in education, employment, health and criminal justice that vary considerably. The fact that, for example, black children of Caribbean descent do less well at school than black children of west African origin is worthy of note, but when the commission concludes that this, like other racial disparities, is mostly accounted for by class and “family structure” (a euphemism for single parenthood, and worse) it begs certain questions.

If black families, say, are more prone to break up and more likely to be on lower incomes and have worse jobs with fewer prospects – well, how and why does this happen? The report is silent on this point, and the implication is that it is the fault of those people that they have not, as others supposedly have, risen above their disadvantages. It is close to declaring that black lives are the way they are today because it is their own fault, and there is not therefore that much government can or should do about it. It is implicit, because it would be too shameful to say out loud, but pernicious nonetheless.

Deconstructing and dismantling “Bame” has something to be said for it – it is a blunt instrument; but not at the cost of dividing ethnic minorities from one another, creating the impression that some minorities are in some way intrinsically or naturally high-achieving and others apparently not so, condemned to an intergenerational self-perpetuating “underclass”, as it was termed by a previous wave of rightist thinkers.

More constructively, the commission is right to identify good education as a pathway to success, but there is little sign that this government is likely to target the resources needed to “level up” opportunities for black people, and the attention of ministers does seem to be cynically targeted on working class, marginal constituencies in the north and Midlands, as well as helping out the Tory shire counties.

This report will be disregarded and forgotten, and rightly so. It was produced by a committee that seemed unaccountably inclined to think that if we all stopped going on about racism it would go away.

The commission’s well-meaning conclusions make no sense even to those who have not had their life chances confined by racism, whatever adjective is attached to it. It is offensive to those who know different, from first hand, to declare that Britain is some sort of beacon example to the world, a land of opportunity and enlightenment. It’s called gaslighting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments