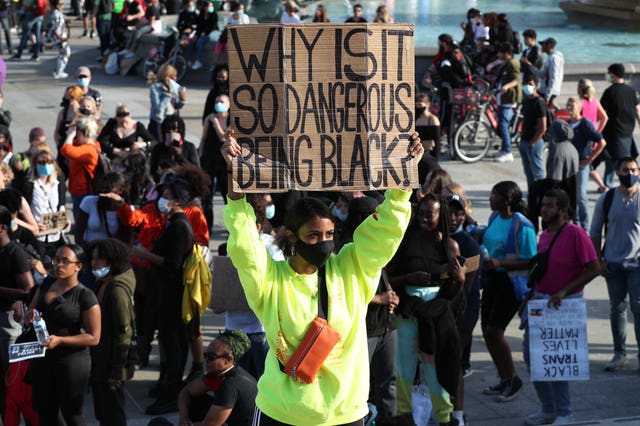

The government needs to tackle institutional racism in Britain once the ‘Bame’ label has been scrapped

There’s still a lot of work to do when it comes to helping ethnic minority communities – getting rid of the term ‘Bame’ is just the tip of the iceberg

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities’ proposal to scrap the catch-all “Bame” label for Black, Asian and minority ethnic people is long overdue, and people are right to laud this move as a step in the right direction – as long as this doesn’t distract from the government’s resounding duty to dismantle institutional racism in this country.

There’s still a lot of work to do in that regard – getting rid of the term is just the tip of the iceberg.

The proposal also raises the question of what will replace the term. In the absence of open consultation and proposals for potential alternatives, one would be forgiven for being sceptical about this move from the government.

British Future, a non-partisan think tank, researched the term Bame in discussion groups with people around the country – and conducted a poll of 2,000 ethnic minority respondents and 1,500 white British respondents – in January and February 2021.

The think tank found that four out of 10 people in the general population think they are confident about what the term Bame means. Most Black, Asian and minority ethnic Britons slightly prefer “ethnic minority” as an umbrella term, with two-thirds (68 per cent) saying they either support or accept the term, while 13 per cent were against it. These findings were considered by the commission.

Read more:

- Let’s take a closer look at what Allegra Stratton describes as Boris Johnson’s ‘honesty and integrity’

- As a Black mother-to-be, I used my husband’s whiteness to keep me safe

- This is supposed to be the trial of Derek Chauvin, not the trial of George Floyd

- Priti Patel doesn’t like my tone, apparently – or is it the facts that worry her?

There’s no denying that the Bame umbrella label is deeply flawed, because different minority groups have different life experiences and face different issues. Many people, including myself, have recognised this for some time.

Lumping ethnic minorities together into one category under the acronym means that the advancement of some communities can hide the fact that others are held back.

Collectivism can sometimes be beneficial – and, of course, when communicating, there is a need to define things. Acronyms make it easier to draw reference to topics. Often, Bame is used across the media as a shorthand for these particular ethnic minority groups.

As a journalist, I’ve used it myself on numerous occasions, in cases where there’s genuinely no alternative. For example, when citing data that has been collated in this way and not broken down by individual groups; in order to be factually correct, the only option is to use the label – as much as it makes me uncomfortable.

But even that isn’t ideal; all too often important statistics relating to non-white people, such as population trends or diversity data within institutions, are squashed together – which opens floodgates for all manner of misrepresentation and inaccuracies. We need to better understand the lived experiences of people within these distinct communities.

In a personal context, as a Black person, I don’t acknowledge the term, because I’m Black – not Bame. It makes me itch when I hear folks refer to themselves as a “Bame person”.

But here’s another question: while overseeing the disuse of the term, will the government see that its own departments and organisations such as the Office for National Statistics start to compile detailed data around ethnic groups to aid in the grand eschewing of Bame?

For example, within ethnic groups such as “Black British Caribbean”, there are more than a dozen sovereign island nations with different cultures therein. Similar can be said for “Black British African” – there are no fewer than 54 sovereign nations across the continent with different languages and cultures. Within the Asian classification, you have north, west, south and east – with dozens of countries throughout. Within the mixed race bracket, there’s a wealth of different ethnicities.

We frequently find “Bame” allows institutions and society to disguise a lack of representation of some groups, by pointing to the inclusion of others. Just last year, the health secretary Matt Hancock named two South Asian cabinet ministers – Rishi Sunak and Priti Patel – when asked how many Black cabinet members there were (the answer, at the time, was zero).

The false indication of racial equality that this often brings across – this veneer of progress – is where serious problems arise and thrive. It can enable organisations to be lazy; apply the jargon sporadically and rest on their laurels, while executives may boast about how they’ve met their diversity quota.

It creates a huge obstacle when it comes to addressing the very real, ongoing issue of systemic racism.

In the UK this usually gives rise to anti-Blackness and, hence, “Bame” does a particular disservice to Black people who often bear the brunt of rooted inequalities – from maternal health outcomes to criminal conviction rates – faring the worst within institutions across society including within, and at the hands of, the government itself.

As I type, uptake of the Covid vaccine is at a devastating low within Black communities, which happen to be dying in disproportionate numbers because of the virus outbreak. This has not been adequately addressed by the government – which appears to be investing more time and energy on splashing £2m into a new Downing Street conference room and quibbling about Union Jacks.

Meanwhile, recommendations from race-related reviews that have previously been produced – such as the Lammy Review, the Windrush Lessons Learned Review, the Angiolini Review, the McGregor-Smith Review and Healing A Divided Britain – sit on the shelves of Westminster, collecting dust.

Boris Johnson’s official spokesperson said that the delayed commission report would be presented to the prime minister by the end of March, and the government would respond “in due course”. He did not give a date for its publication.

The spokesperson added: “The government doesn’t routinely use the term Bame or BME, because they are not well understood and because they include some groups and not others. For example, the UK’s ethnic minorities include white minorities and people of a mixed ethnic background.

“Similarly, we do not use the term ‘people of colour’ as it doesn’t include white minorities.”

The nation has been waiting for this report for nine months. Let’s hope that it births real change.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments