Stagflation, strikes, travel chaos: The UK must prepare for dark days ahead

Editorial: The misery is far from over. It’s no time for any government to be optimistic about winning the next general election

Pity the British traveller looking for a few weeks in the foreign sun this year. Assuming they’ve got their passports back, assuming their flights aren’t cancelled, assuming they are able to get to an airport on a national rail strike day; there is now the probability that there’ll be no one on duty at Heathrow to check them in and get their luggage on board.

Then, if they’re unlucky, they will arrive at a European airport that directs them to an interminable queue at post-Brexit “third country” passport control. The glamour is certainly draining from the jet set.

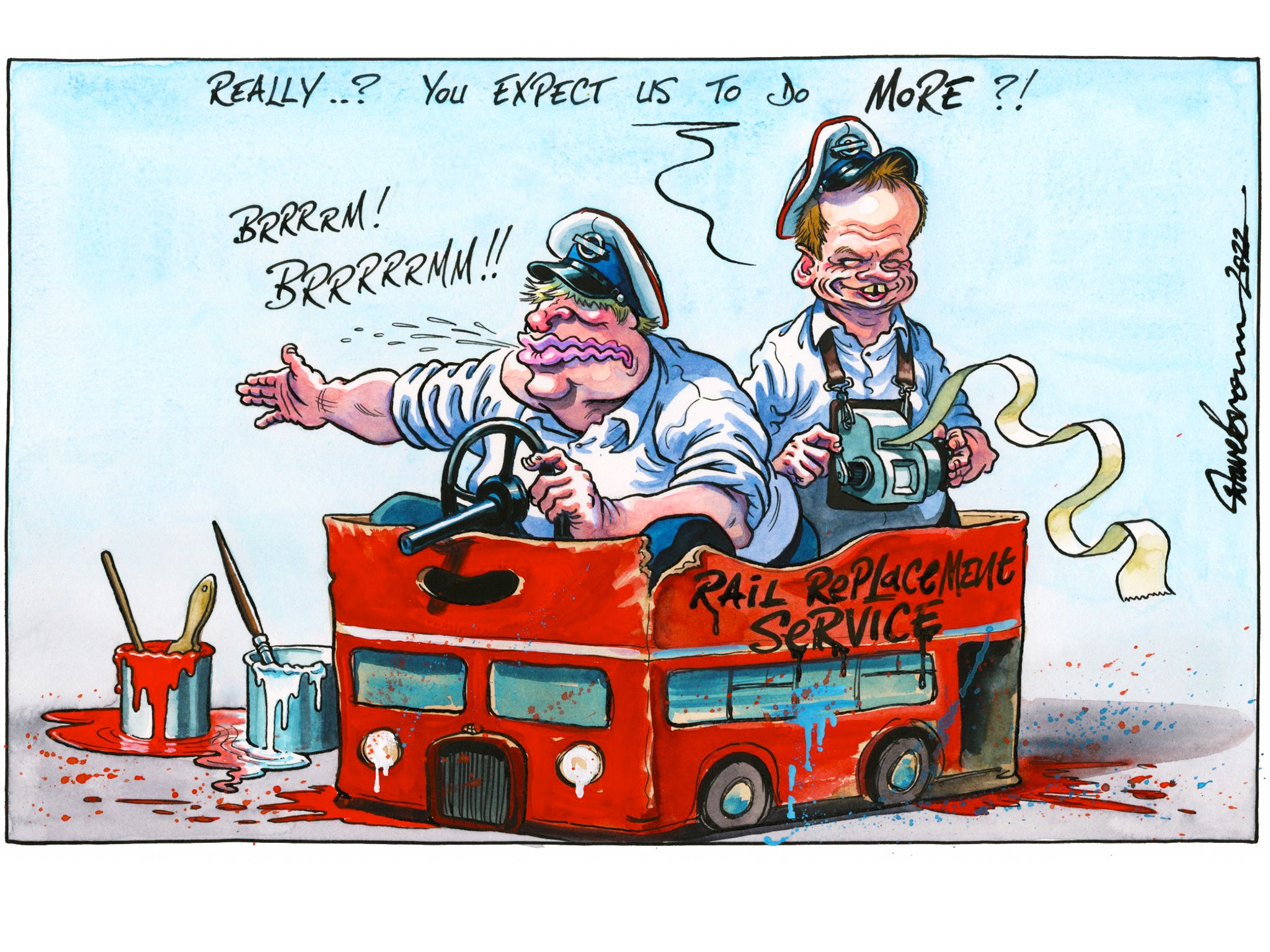

Such is the growing tumult in industrial relations that life generally seems set to be disrupted on a scale not seen in decades. Maybe talk of a “summer of discontent” is overheated – days lost to strike action are unlikely to surpass the peaks seen in the winter of 1978-79 – but the disruption and unease will be widespread and more than inconvenient.

Given the present mood, it seems likely that the rail strikes will continue, on and off, for many months, and that criminal barristers, teachers, nurses, doctors, care workers and local authority refuse collectors will also withdraw their labour.

That would be difficult enough for people to cope with without the other obstacles to normal life that have presented themselves: inflation heading for 11 per cent, soaring energy bills, petrol at £2 a litre and rising, higher mortgage bills and borrowing costs, meagre pay rises, shortages of workers, tax hikes, real-terms cuts to benefits, food banks unable to meet the demand for the basic necessities of family life, longer waiting lists, slower ambulance responses, and scarce GP appointments, and long delays for driving licences – and, before long, a full-on recession.

There is a sense of national malaise growing in Britain. The good years seem to be over. An economic model that was based on low inflation, the EU single market, a flexible labour market assisted by free movement of workers in and out of the economy to match shortages, inward investment, globalisation and industrial harmony has given way to a nightmarishly dysfunctional economy.

“Stagflation” is a miserable word for a miserable economy, and the most depressing thing of all is that the government doesn’t know what to do. It is, in truth, a difficult dilemma; growth but with accelerating inflation; or a sharp recession biting hard on already depressed living standards.

Either policy has some merits; but at the moment, the government seems unable to commit to either. It’s not much help to suggest that Brexit has uniquely exacerbated the challenges faced by nations around the world, but it is a matter of fact that it has hurt business confidence and investment, and thus stymied productivity and wage growth, and has done so since the referendum, six sorry years ago.

There have been emergency measures to deal with isolated problems, which are welcome, and the Treasury designed an excellent support structure for jobs during the lockdowns. But there is a sense of drift now, of dither and delay, about how to keep the economy growing without the labour force it needs, and protecting the vulnerable and hard-working families; while simultaneously supporting the Bank of England by bearing down on demand, resisting pay demands, and thus squeezing inflation out of the system.

The wave of strikes that is going to overwhelm the authorities in the coming months aren’t due to a sudden outbreak of Marxism or because of soft laws on strikes. Quite the opposite. It is simply a matter of supply and demand.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

It is no surprise that in a tight labour market the unions, and non-unionised labour in shortage occupations, can name their price. Union power and the inevitable success of the strikes will be because vacancies presently exceed the numbers looking for work, and unemployment is at its lowest since 1974. What would anyone expect when the flow of EU skilled and unskilled workers dried up and long Covid took around 400,000 out of the labour market?

The UK economy has lost a significant proportion of its productive capacity because of a shortage of labour and a shortage of private sector investment. In economist jargon, aggregate supply has fallen back, and with aggregate demand still not adjusting downwards, wage and cost inflation is unavoidable.

Given that Brexit isn’t about to be reversed, and public debt is high, the only way to drive inflation out of the system is to hammer demand through interest-rate hikes, tax rises and public spending cuts – and a larger pool of unemployed to dissolve worker power. The misery is far from over. It’s no time for any government to have much hope of winning the next general election.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks