If Boris Johnson wants to avoid a return to 1970s strikes and stagflation, he must take control

Editorial: The last time this country suffered from strikes, inflation and poor growth, it didn’t work out well for the government

The more that ministers, including the prime minister, warn against a return to the wage-price spiral of the 1970s, the less well it reflects on their management of the economy.

Simon Clarke, the chief secretary to the Treasury, said that workers could not expect their pay to keep up with prices. “That is what the governments of the 1970s failed to address,” he said, pointing out that once inflationary expectations become “baked in” they become self-fulfilling.

He was merely repeating what Boris Johnson said in his Blackpool speech 10 days ago: “If wages continually chase the increase in prices, then we risk a wage-price spiral such as this country experienced in the 1970s – stagflation. That is, inflation combined with stagnant economic growth.”

This, of course, is the same Mr Johnson who told us only a few months ago that an increase in wages for those doing certain types of manual work was one of the benefits of Brexit, for which the people voted six years ago. Those benefits are largely failing to materialise in the lowest-paid sectors. Although some lorry drivers may be better off, nurses and careworkers continue to see wages kept low by the recruitment of non-EU staff from abroad.

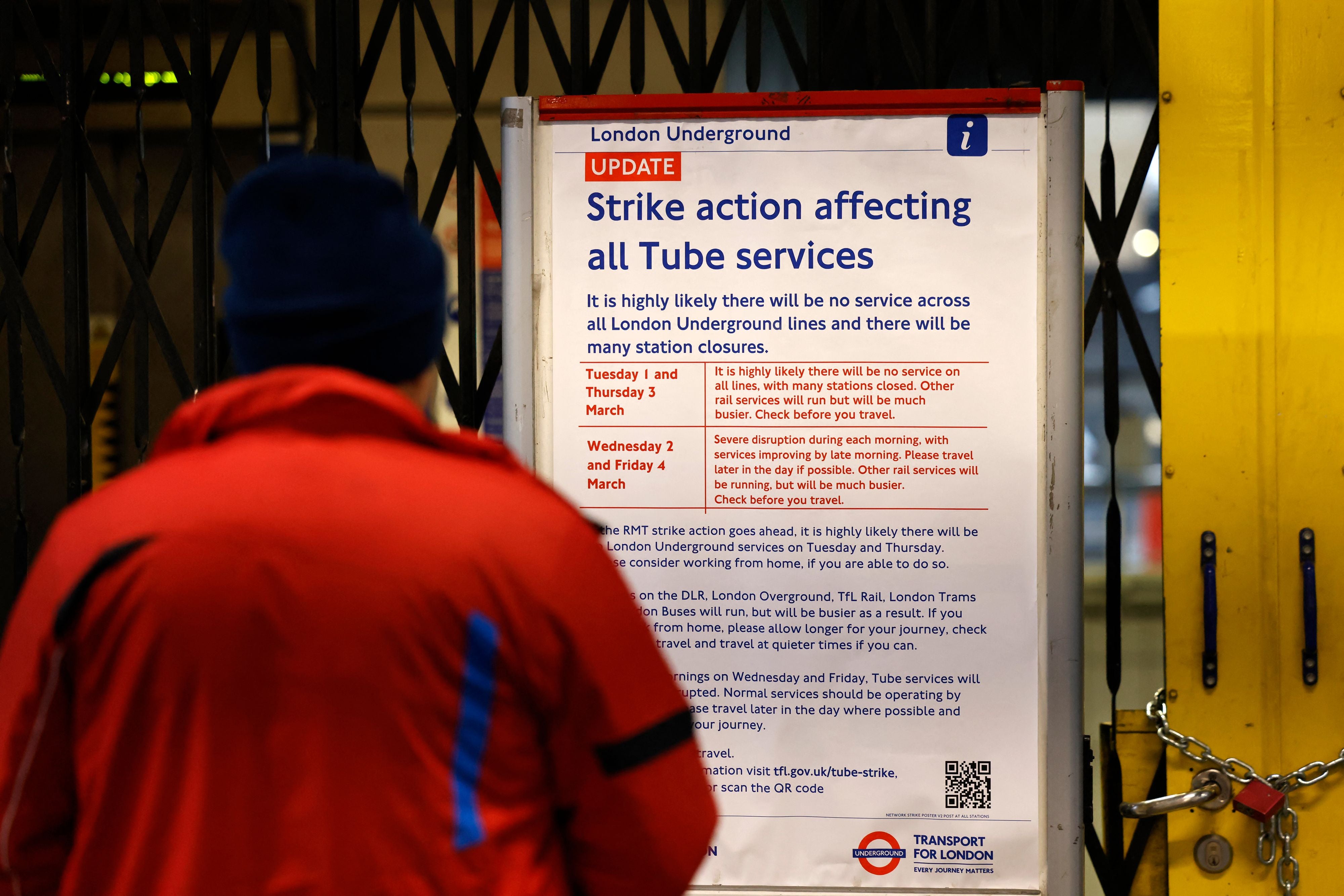

Meanwhile, Mr Johnson has executed a three-point turn in his rhetoric, and is lecturing rail workers on the selfishness of seeking a big pay rise. Worse than that, he is trying to blame the Labour opposition for the strikes taking place over the coming week. This is doubly absurd – not only because Labour is not in government, as Sir Keir Starmer pointed out at Prime Minister’s Questions, but because the Rail, Maritime and Transport union, which is leading the strikes, is not even affiliated to the Labour Party, its ruling body having engaged in abstruse syndicalist splittery.

Grant Shapps, the transport secretary, is trying to distract attention from his own responsibilities by claiming that the dispute between the unions and the train-operating companies is nothing to do with the government. Fortunately, the British public is not going to fall for that one. Most people have some sympathy for workers trying to defend jobs, pay and conditions, even if they find strikes frustrating, and they expect the government to do its best to sort it out. They recognise, after all, that the railways are a semi-nationalised industry.

If the unions are behaving unreasonably, then it is Mr Shapps’s duty to make that case and defend it, rather than to pretend that it is none of his business or to blame Labour. After all, it is more in the interests of the Conservative Party than those of the Labour Party that this dispute is resolved.

Sir Keir was quite wrong to say, in his speech to the Labour Local Government Association conference that we report today, that Mr Johnson and Mr Shapps “want the country to grind to a halt so they can feed off the division”. That seems unlikely. Mr Johnson seems to be engaged in a desperate damage-limitation – or damage-diffusion – exercise. If the country does grind to a halt, the prime minister knows that people will ultimately blame the government.

Even if they do not blame the government directly, they will sense a lack of grip, and will feel – as they did in the latter half of the 1970s – that the government has no idea how to get the economy back on track.

Mr Johnson and Mr Shapps need to stop the diversions and distractions and “take back control” if they want to avoid the fate that awaited James Callaghan at the ballot box in 1979.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments