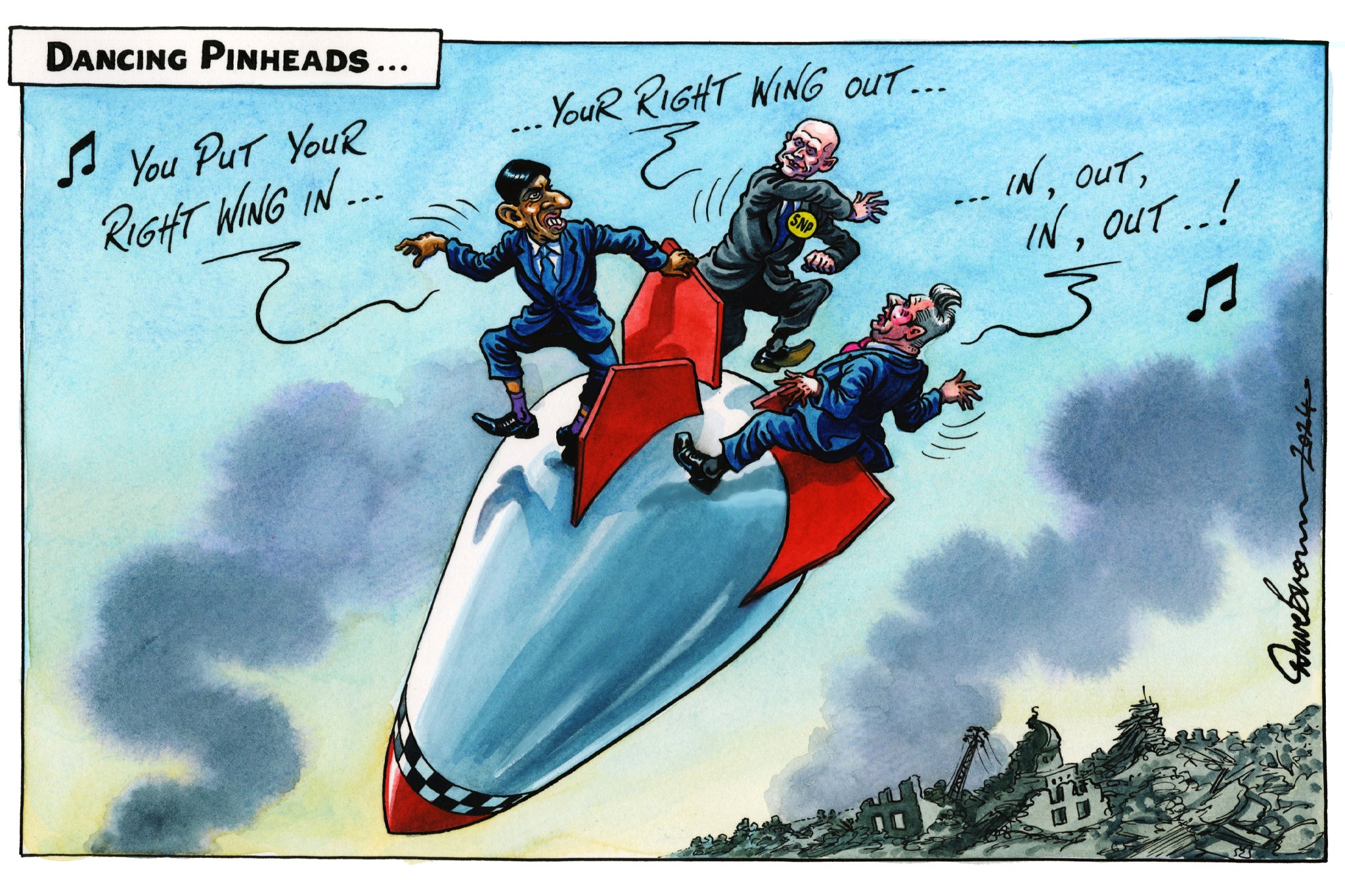

Now the war in Gaza is poisoning British politics

Editorial: A rancorous Commons debate about ending conflict in the region showed parliament’s adversarial procedures to be unsuited to easing such tensions. MPs would do well to remember the scale of the human suffering – and the importance of a permanent peace

According to the motions presented by the political parties on Wednesday, during the latest Commons debate on the war in Gaza, their attitudes may be summarised as follows. The Scottish National Party wants “an immediate ceasefire in Gaza and Israel”. The Labour Party is calling for “an immediate humanitarian ceasefire”. The Conservative government’s policy is for “an immediate humanitarian pause”.

Some might wonder how such minor differences in phrase and meaning could eventually result in the Commons collapsing into total chaos. The fiasco over voting was both arcane and tragic.

The speaker, Sir Lindsay Hoyle, broke with tradition and tried to have three votes on each party’s motion, thus allowing all sides to have their different says on a matter of national importance. It also meant, in some cases, members could vote in a way that matched their own view more closely, and protected them personally from outside pressure from constituents about their stance.

The clerk of the House publicly warned the speaker that his ruling carried the risk of the SNP being denied an opportunity for all MPs to vote on their substantive motion on their Opposition Day motion.

Sir Lindsay took the risk and was let down by the government changing its tactics. The result is a crisis of confidence in the speaker – and the Commons making collective fools of themselves in front of the public.

Allegations that Labour threatened the speaker with the sack after the election added further discord, and was the most important story to emerge from the imbroglio. Sir Lindsay’s abject apology will probably protect him from being the third speaker in a row, and a little more than a decade, to effectively be ousted by MPs; but his authority has suffered.

Opposition Day debates are not supposed to end up like this, and they usually don’t when they’re concerned with mundane policy matters – but the root of the farcical scenes is not to be found in Erskine May but in the dust and rubble of Gaza. It highlights, painfully, how the British parliament is unable to speak with one voice on the single most immediate issue at stake – and where differences are relatively narrow.

Though it would be a constitutional novelty, and a reversal, of the usual conventions, perhaps the politicians should have taken the advice of Prince William and simply called for “an end to the fighting”.

It may, after the bitter rows and walkouts in the chamber, seem hopelessly unrealistic to expect consensus on any aspect of politics in the Middle East. But, in fact, all the main parties actually agree on the aim of a “two-state” solution and, in a more recent evolution of that long-standing formula, a formal recognition of a Palestinian state sooner rather than later – and at the beginning of a peace process, rather than at the distant conclusion of one.

The contrasts with the war in Ukraine are also instructive. Since day one of the Russian invasion, and indeed from the time when that grim prospect first hoved into view, there was broad agreement on all sides that such Russian aggression was unprovoked, unjustified and illegal; and that the Ukrainians should be sent all forms of assistance as soon as possible. That consensus has held in the UK, and minor differences over policy set aside.

The war in Gaza is poisoning British politics, with the left, broadly defined, caricatured as being unconditionally pro-Palestine (or even pro-Hamas and pro-terror); and the right portrayed as pro-Israel (or even pro-genocide). Some of the arguments – in parliament, online, in demonstrations – twist the motives and policies of opponents grotesquely.

It is a dangerous situation, and one that doesn’t reflect the actual agreement on the situation that could exist if people sought common ground. Without that effort, Britain will continue to suffer a rise in antisemitism and in Islamophobia, and every community will suffer as a result. This is not how it should be, and parliament’s adversarial habits are not well suited to easing these tensions. Indeed, on this occasion, they exacerbated tensions.

A greater degree of consensus about the desirability of an end to the fighting in Gaza might well also help Lord Cameron in his efforts to dissuade Benjamin Netanyahu from launching in Rafah what all agree would be a catastrophic land offensive supported by aerial bombardment on around a million and a half people sheltering in tents and rubble. Around a half of them children, many orphans.

Even after 29,000 deaths and all the horrors that have gone before – including the atrocities committed by Hamas on 7 October – it seems likely there will be more horrors to come. Many more lives will be a lost, more innocents maimed, more infants left without family.

In some wars, what some call “just” wars, there is a point to the loss of life, where it is proportionate, complying with international humanitarian norms, and for plausible war aims. The Israeli campaign, if it ever was, is not going to conform to any of those standards of the conduct of war if Rafah is bombed into oblivion.

Israel’s right to defend itself doesn’t grant it the right to defy international law. But more pertinently, from the point of view of Israel, such an attack will not make Israel more secure. Flattening Rafah, or anywhere else, will not end the terrorism and it will not help Israel normalise its relationships with its neighbours.

The coming battle for Rafah is, we may be sure, going to push the International Court of Justice closer to a judgment of genocide against the state of Israel. What it will also do is intensify the suffering, risk escalating and spreading the conflict (as it already has), and fracture Israel’s relations with America and others who stood with Israel in October.

As the Prince of Wales said: “Sometimes, it is only when faced with the sheer scale of human suffering that the importance of permanent peace is brought home.”

That time has surely come. Maybe our political leaders can agree on that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments