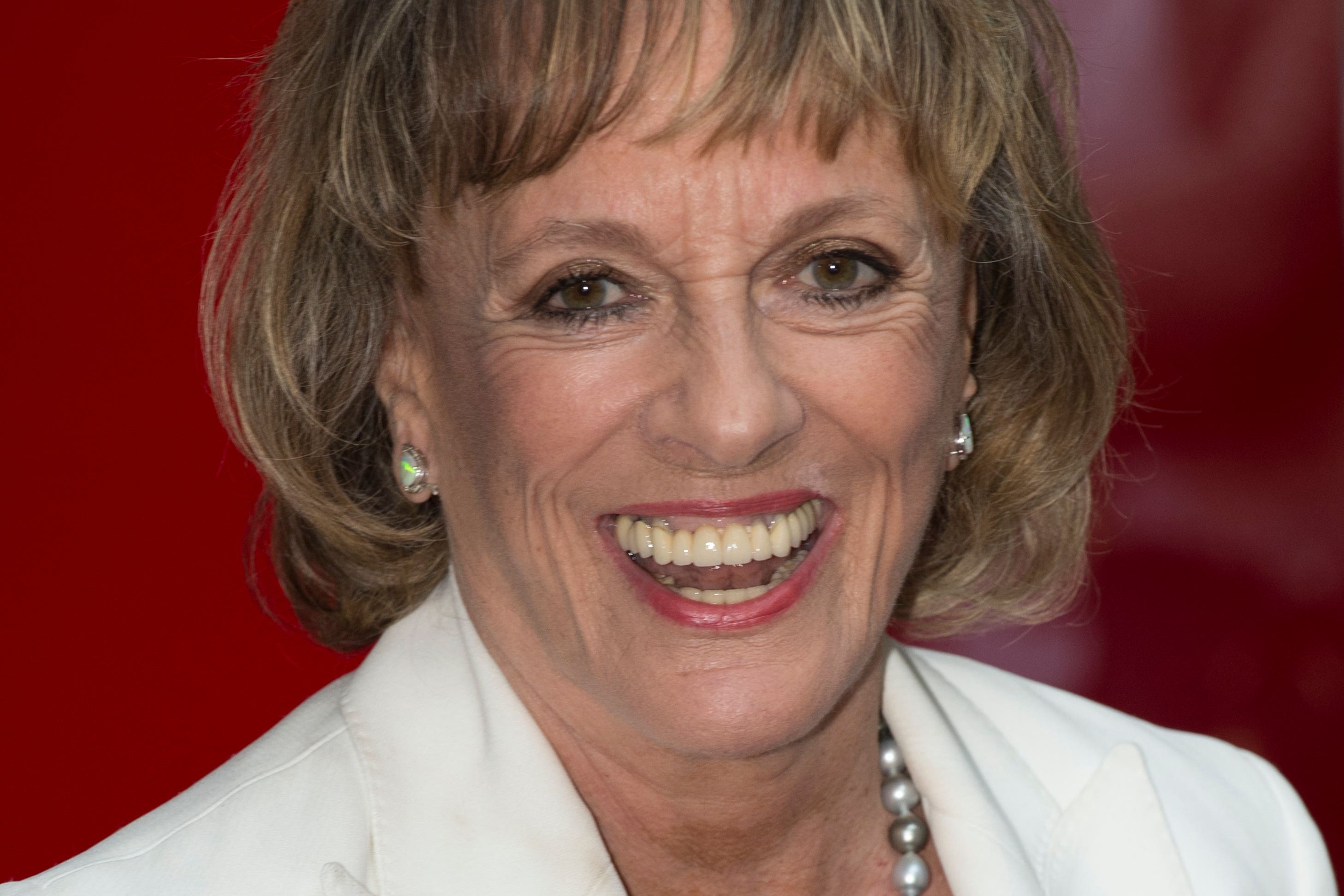

We hope Dame Esther Rantzen will see her campaign to legalise assisted dying come to pass

Editorial: If parliament lives up to the challenge, this will be a historic piece of social legislation; as significant in its way as previous private members’ bills on abortion, the death penalty, equal marriage and divorce reform

Dame Esther Rantzen cheerfully admits that she feels fortunate to have lived long enough to see her campaign to legalise assisted dying move close to success.

A parliamentary bill now being introduced in the Commons has a highly realistic chance of becoming law. Indeed, there is already one such bill already making its way through the House of Lords, sponsored by Lord (Charlie) Falconer, who served as a law officer under Tony Blair.

The Commons bill may be more likely to end up on the statute book, however. As a private members’ bill at the top of the ballot, its sponsor – Kim Leadbetter – is guaranteed time for the legislation to be properly considered and not filibustered into irrelevance.

The bill will be introduced in a fortnight and has already provoked a dignified and measured debate. It is a great help to Ms Leadbetter – and, by extension, to Dame Esther and other campaigners – that the government will be “neutral” on the issue and that the prime minister has previously voted in favour of such a measure. Some MPs will take that as a cue to back it.

As is entirely right, the parliamentary proceedings will be a “free vote” and party politics will be kept out of it. It is a classic question of conscience, with deep religious and ethical dimensions. MPs and peers should be permitted to vote (or abstain) based on their sincerely held beliefs and independent judgements. Lobbying is appropriate; intimidation is not.

Controversial as the issue is – and with genuine passion and compassion more than evident on all sides – a consensus seems to be emerging about the proposed new law (for England and Wales), just as it has in Scotland, Jersey and the Isle of Man, where reform is already being pondered.

The principle that some people – clearly in intolerable pain and suffering, physically and mentally – should be able to choose how (and when) they die recommends itself on the grounds of compassion and common sense.

Some, understandably, stand for the sanctity of life as inviolable in all circumstances; something that cannot be abrogated by mere man-made law – a parliamentary majority doesn’t confer moral right on anything.

The right to life, after all, is a human right; a right to death doesn’t necessarily follow. Yet laws and (rather less satisfactorily) medical custom and practice already exist to govern – loosely and informally – what might even now be termed a de facto assisted dying regime. The present arrangements also have obvious drawbacks. There is no harm in revisiting them.

As Dame Esther puts it so directly, there is a strong element of bodily autonomy and personal choice underlying her cause – one made all the more powerful and authentic because it applies to her (she has already joined Dignitas).

There can come a point in the progress of a terminally ill patient when they are unable to exercise that choice at the relevant time. Even if they are, they may be unable to exercise it and to travel – usually to Switzerland – independently; requiring friends or family to risk prosecution.

Such awkward and painful cases have already arisen – and their treatment in the criminal justice system hasn’t always been consistent or appropriate in the eyes of many. These questions should be confronted.

If there is consensus on the principle that assisted dying should be lawful in certain circumstances – and with strong safeguards against abuse – then it is essential to minimise the potential for misunderstandings, pressuring the dying or hastening an end for financial gain.

Multiple medical opinions about whether a condition is truly “terminal” must be obtained before anything happens. The same goes for ensuring all options regarding palliative care have been exhausted. There can be no question of the decision being made for the administrative convenience of any institution before all treatments have been tried.

This point is made most thoughtfully and eloquently by Wes Streeting, the health secretary: “Candidly, when I think about this question of being a burden, I do not think that palliative care, end-of-life care in this country is in a condition yet where we are giving people the freedom to choose, without being coerced by the lack of support available.”

Medical staff should be able to opt out of taking part in assisted dying where it violates their moral codes.

Where there are potentially substantial financial obligations, there should be legal opinion as to the probity of any interested parties – a freely composed, definitive will is more crucial than ever in these circumstances. A “living will”, issued by the terminally ill, should guide any future medical and other judgements. (A greater adoption of binding or non-binding wills might well reduce the agonies of loved ones faced with deciding the fate of someone taken suddenly seriously ill.)

Those involved in an assisted dying procedure should never feel themselves to be above the law, or in any way absolved of the usual duties of care and respect for life. Any procedure has to be protected by the severest of penalties for those found to have abused it, for whatever motive.

Ms Leadbetter has wisely chosen to promote a cause that commands wide public support. If parliament lives up to the challenge, hers will be a historic piece of social legislation; as significant in its way as previous private members’ bills on abortion, the death penalty, equal marriage and divorce reform.

All have been transformative. We can only hope that Dame Esther will celebrate seeing it gain royal assent.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks