I’m a Black woman, but I still won’t say ‘Bame’

Why do some politicians and business leaders insist on using a term that lumps together Black, Asian and minority ethnic, asks Ava Vidal. You may as well change it to YL – You Lot

I thought we’d said bye-bye to Bame. The acronym – a neat catch-all for “Black, Asian and minority ethnic”, and bound up in quite old-fashioned notions of political blackness – gained traction in Britain in the 1970s when it was taken up by well-intentioned anti-racist movements.

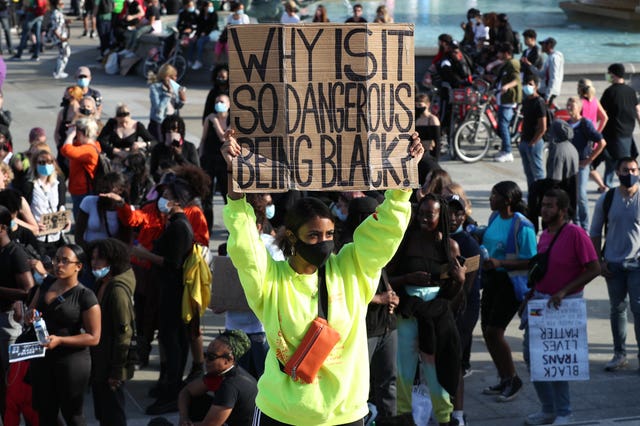

After really getting going in the 2010s, when policymakers and people working in officialdom couldn’t say it often enough, “Bame” promptly dropped dead – not uncoincidentally around the same time the racial justice movement took off after the 2021 murder of George Floyd. Bame expired under the weight of its own contradictions.

And, well… good. I, for one, am not Bame. I’m Black.

As any umbrella term that lumps together a hugely diverse set of people, it is obviously problematic – just ask any “LGBTQ+-er”. When taken as a stand-in for “non-white”, it can be unnecessarily divisive. It emphasises certain ethnic minority groups and excludes others, not least those from a mixed-race background. Also, it rhymes with “blame”, which is a bit on the nose, in the circumstances.

The National Council of Voluntary Organisations (NCVO) recently stopped using the word, preferring the term “global majority”, which is awkward in new and different ways. But at least they’re trying to stamp it out.

So why am I still hearing the B-word? (You know who you are…)

It was around the time of Blackout Tuesday – when, in 2020, millions of people around the world posted a plain black square on social media and promised to do better (remember that?) – that I noticed people had started tiptoeing around. Some even asked, in all seriousness, if it was racist to call someone “Black”. “Bame” felt safer, kinder – much like the long-rejected descriptor “coloured”.

At one point, I changed my username on Twitter to “No such thing as Bame”, and got battered by left and right for rejecting it. I was told the Labour Party had been using the word, and when I raised an objection, I was told to “get over myself”. A lot of the responses I got could be summarised as: “We’ve acknowledged you’re not white – what more do you people want?”

The ridiculousness of lumping minorities was hammered home when I was told by (yet another) white TV producer that there was no need for a Black show such as the one I was pitching. “We have Bame,” she said. “I’m a woman.”

She then held my shoulders, stared me in the face and said, earnestly: “We are all minorities now.”

People of Britain, once and for all, please get the B-word out of your mouth.

In my hatred of the dreaded acronym, I find myself in agreement with Lord Sewell, the Tory peer and controversial chairman of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, a man who has previously been accused of being way out of step with public opinion on race matters.

While promoting his latest book, Black Success, he declared that categorising all racial minorities in one group was regressive: “The life of somebody who is a Pakistani background taxi driver from Bradford is completely different from someone who is an Indian Hindu doctor living in Harrow.”

Rather than simply using non-white skin colour as a unifying factor, he believes we should dig much deeper and look as well at social mobility, social cohesion and disparity – “with race not necessarily at the forefront”.

I wholeheartedly agree with this sentiment, as do many Caribbean heritage people who baulk at being casually lumped in with Africans, or British Chinese who resent being spoken in the same breath as South Asians. It is lazy, reductive and grossly dehumanising. Black, Asian and minority ethnic? You may as well change it to YL – You Lot.

According to Sewell, in an interview he gave recently to LBC’s Iain Dale, one way to tell how people from a Bame background are faring within a society – and highlighting in an instant how reductive and nonsensical it is to group them into one acronym – is to look at how well or otherwise they are doing in education. “The group that I’m from, the Caribbean group, still does poorly,” he said. “But the African group is doing so well – in the same schools.”

Where I leave Sewell behind is in his claim that this disparity exists because Caribbean households have a higher number of single mothers than their African counterparts. In a list of those who are responsible for all that’s wrong with modern society, Caribbean single mothers are right up there – on a par with Liz Truss. Or Ed Sheeran.

While I agree with Sewell about Bame as a term, I question his framing of the conversation around it – which, to me, is like putting a fresh coat of paint over a mould patch without addressing the root cause of the problem.

The Caribbean itself has a 94.29 per cent literacy rate, and the University of West Indies one of the top ranking universities in the world. Coming from that background myself, I can confirm that the emphasis on getting a good education is a high priority. The problem is simply not cultural.

Sewell is also guilty of that which he criticises, because not all Africans are performing well in terms of educational attainment. There is a vast difference between Somalians and Nigerians, for example.

Famously, Sewell has no truck with the structural inequalities that render Bame redundant. His 2021 report into race in contemporary Britain concluded that we do not have a problem with structural racism – a finding so incendiary and wrong-headed, it was criticised by pretty much every section of the community it purported to report on, from public health to academia. UN human rights specialists recommended his “Report on Race and Ethnic Disparities” be rejected by the government for fear it would help to “normalise white supremacy”. Baroness Doreen Lawrence went so far as to warn that the report risked pushing the fight against racism “back 20 years or more”. After publication, Nottingham University withdrew its offer to Sewell of an honorary degree.

Sewell also fails to acknowledge the harsh, racist treatment received by the Windrush generation on their arrival to these shores, which included educational inequalities that resulting in two generations of Caribbean children being disproportionately and unfairly being placed into educationally subnormal schools. This meant their prospects were severely limited, and unable to get decent jobs, trapping them into a cycle of poverty. This shameful episode is brought home by the BBC documentary, Subnormal: a British Scandal.

See also the criminalisation of the British Caribbean community through ‘sus’ laws (short for suspected person) which, until they were outlawed in 1981, were stop-and-search powers used by the police to harass Black people. The lasting impact of ‘sus’ was detailed so well in Stafford Scott’s groundbreaking 2021 ICA exhibition, War Inna Babylon.

The erasure of categories meant Bame inadvertently highlighted the disparity it aimed to address. It became a parody of itself. It united Indians and Pakistanis, Nigerians and Ghanaians, Jamaicans and, well… the rest of the Caribbean. For a while, we were one. United. As if that could ever work! And that alone should have let us know Bame was doomed to fail.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks