What did codebreaker Alan Turing do to deserve being dragged back to life like this?

The tortured mathematical genius who helped defeat the Nazis – and invented AI in the process – has been resurrected digitally. Is this what he would really have wanted his technology to be used for, wonders Paul Clements

If you’ve been on social media lately, you will have seen it – the viral ad in which Alan Turing is brought back to life by the artificial intelligence he made possible, to promote a firm selling chatbot learning courses. Your algorithms may have spared you the video so far, but it, and the furore it has generated, is but a click away.

Singaporean tech company Genius Group has magically “revived” the tortured mathematical genius in digitised form and, in a move that’s somehow even more objectionable, have “appointed” him as its chief AI officer.

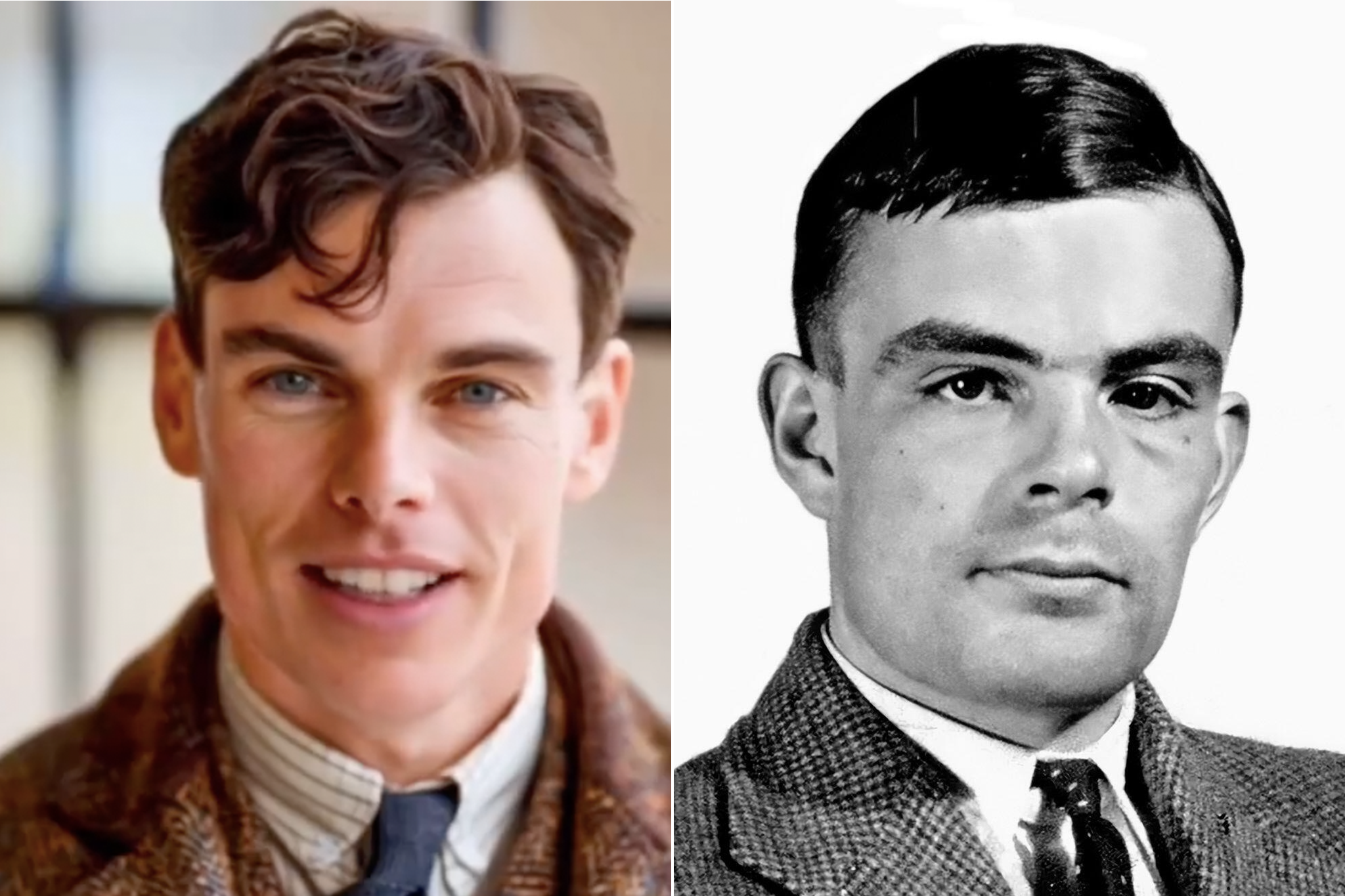

Looking raffish and rugged, the floppy-haired and, dare I say, dashing Turing avatar – think Benedict Cumberbatch, who played Turing in The Imitation Game, but more chiselled of jaw, broader of chest and less wonky of eye – is heard to intone, in a wandering, transatlantic accent: “The real me died 70 years ago. My gosh, you’ve all been busy, haven’t you, while I’ve been away… Anyways, nice to be back."

It’s an “ugh” from me. It’s somehow more obnoxious than the AI chatbot voice given to the Elon Musk impersonation on Radio 4’s Dead Ringers.

To many, this is a debasement of Turing’s contribution and his memory, an outrageous overstepping of an online red line. He was one of the most consequential British figures of the 20th century, a mathematician and cryptographer whose work at Bletchley Park was instrumental in cracking the Nazi Enigma code and ending the war, a pioneer of modern computer science and forefather of artificial intelligence we all enjoy today. Latterly, he became a gay martyr, hounded to his death because of his homosexuality. Without him, we’d not only all be speaking German, we’d have mobile phones running on Fortran.

It almost doesn’t matter that Turing finds himself in esteemed company – the geniuses at Genius have also given the same dubious AI makeover to consequential historical figures such as Albert Einstein and Marco Polo. What’s interesting is that it’s Turing’s resurrection that has sparked the outrage.

The man is a hero to many. Today, his face is on our banknotes (in a nice touch, the pink-tinted £50 ones). In 2009, he was given a posthumous apology from prime minister Gordon Brown, later upgraded to a full royal pardon for Turing’s 1952 gross indecency conviction. Until he is immortalised on Trafalgar Square’s fourth plinth, the most touching tribute to him is A Man From the Future, an ambitious electronic oratorio by the Pet Shop Boys that received its premiere at the 2014 Proms. (The great shame is that it hasn’t been performed since.)

So why drag Turing back to life now? Next month will mark 70 years since his suicide, aged 41, by eating a red apple that he had injected with cyanide. The half-eaten core was found by his body, which had become flabby, his chest engorged into breasts, after two years of the hormone therapy to which he submitted himself as punishment for his crime. In 1950s Britain, homosexuality could mean life imprisonment. Having tried chemical castration, Turing chose death.

And yet, he is risen, digitally dug up to suffer new indignities as a corporate tool. Much of the opprobrium stems from the bot-makers having resurrected him not as a backroom billy who spent the war in a hut, building computational devices, but as a dashing lunk in the mould of a daring Spitfire ace – of the kind that would be generated if the AI image search was for “British war hero”. Andrew Hodges’s brilliant 1982 biography, Alan Turing: The Enigma, makes clear he was a loner whose love of cross-country running fed his outsider status and helped him maintain a puny frame.

Of all of Turing’s scientific discoveries, one of his most enduring is the Turing Test – the simple method he devised of determining whether a machine can pass as human. He believed a computer can be said to possess artificial intelligence if it can mimic human responses. This ‘imitation game’ remains the ultimate goal of AI developers – to fool users into believing that software is flesh and blood.

But that liminal space between reality and artificiality is the existential faultline on which modern society now finds itself. One example is the use of AI to create digital likenesses of actors, which became a major bone of contention during last year’s Hollywood strike. Leading stars have every right to fear they will one day lose control of their most lucrative property – themselves. Tom Hanks was indignant when his voice was recreated by AI, without his knowledge or consent, for use in a dental commercial. Robin Williams’s daughter was horrified that her late father’s voice could so easily be summoned for use in the sequels he could not be involved with.

That said, as for Turing, I suspect he would have been thrilled about being digitally brought back to life – not just because of his new, matinee-idol good looks, but because the project is living proof of his world-shaping ideas, whose distruptive potential he never saw fulfilled.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks