Van Gogh’s London: How the artist fell in love with the UK capital

As a new exhibition opens at the Tate, Juliet Rix explores the Dutch post-impressionist’s infatuation with the Big Smoke

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An ordinary 19th-century terraced house in a pleasant Brixton street, 87 Hackford Road, is undergoing careful renovation. It is a listed building, but not for its architecture. This is the first known UK home of one of the world’s most popular artists, subject of the Tate’s latest exhibition, Van Gogh and Britain.

Vincent Van Gogh arrived here in 1873 aged just 20. He was not yet an artist, but according to leading expert Louis Van Tilborgh, “the Van Gogh we know was born in London”.

Vincent came here to work for a Dutch art dealer, Goupil & Cie, in Covent Garden, and six days a week he walked three-and-a-half miles to work. I am about to set off in his footsteps, but first a peep inside the Van Gogh House.

Recently bought by an Anglo-Chinese family (Van Gogh was one of very few western artists acceptable in Communist China, and remains hugely popular), the house is shortly to open as a centre for artists-in-residence, with bi-weekly public tours.

A narrow wooden staircase (such as you might see in a Van Gogh interior) leads up to the second floor where Vincent lived in the front room. The rest of the house was occupied by his landlady, a little school she ran, and her 19-year-old daughter with whom Vincent seems to have fallen unfortunately in love. She was engaged to the previous lodger, and this disappointment may well have been the reason he eventually moved to a nearby boarding house in Kennington Road.

In the meantime, he was happy at Hackford Road. In fact, his sister-in-law suggests this was the happiest time in his adult life. He planted sweet peas and poppies in the garden (soon to be planted here again) and wrote to his brother Theo: “I have a wonderful home and it’s a great pleasure for me to observe London and the English way of life.”

I set off past townhouses unchanged since Van Gogh’s day. Along Mowll Street, called Chapel Road in 1873, the chapel has been replaced by a striking Art Nouveau and Byzantine Revival church (decorated with Eric Gill lettering) and the cosy vegan Van Gogh cafe. But on Brixton Road, the vast, temple-like St Mark’s Church is little changed and opposite it still stands the Oval cricket ground.

“With the Oval on his doorstep, it’s almost inconceivable that he never went – if only to see what English cricket was like,” says Martin Bailey, Van Gogh biographer and co-curator of the Tate exhibition. He may also have seen the game played across the road in Kennington Park as he walked on. Van Gogh loved London’s “splendid parks, with a wealth of flowers such as I’ve seen nowhere else”, and he regularly visited Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park, where he watched the upper-classes parading along Rotten Row.

Van Gogh’s commute took in the full gamut of London life, from artistic riches to heavy industry, elegant wealth to grinding poverty – poverty he read about in the novels of Charles Dickens, who died just three years before he arrived in London.

Along Black Prince Road, Vincent would have passed the Lambeth Workhouse (today, a council estate) and the imposing industrial edifice of Doulton Pottery, now home to clean, quiet, digital workspaces.

At the end of the road rise the skeletal ribs of White Hart Dock, the last survivor of the port facilities built alongside the Albert Embankment just five years before Van Gogh was here. I follow the Thames, now infinitely calmer than in its Victorian commercial heyday, but with many buildings Van Gogh would have known, including the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Lambeth Palace and its neighbouring church – today, the nation’s only Garden Museum.

Van Gogh crossed the river at Westminster Bridge and noted with an artist’s eye the scene that would become so beloved of impressionist Claude Monet. Van Gogh wrote later to Theo from Paris where he had just seen a painting of a rainy Westminster Bridge: “I know what it looks like when the sun’s setting behind Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament … Early in the morning, and in the winter with snow and fog. When I saw this painting I felt how much I love London.”

From Westminster, Vincent may have walked up Whitehall to Trafalgar Square (where Landseer’s Lions had been recently installed) and the National Gallery. He certainly got to know the pictures here – as he did at the British Museum and Royal Academy. It would astonish the young Van Gogh to know that his own work now hangs in the National Gallery, and even more that his most famous painting, the Sunflowers, is currently on loan to an exhibition just upriver, dedicated entirely to him.

The Strand in Van Gogh’s time was known for its street-walkers, but also as the centre of London’s book and print trade. Each week, Van Gogh strolled up to No 190-198, opposite Christopher Wren’s Church of St Clement Danes, to see the images in the latest edition of The Illustrated London News. While in London this artist-to-be amassed a remarkable collection of some 2,000 prints, from which he took inspiration throughout his life.

Van Gogh was employed by a print seller just off the Strand on Southampton Street, now better known for camping kit and coffee shops. Ahead is Covent Garden Market, then a hubbub of fruit and vegetable sellers, today a cluster of smart boutiques and a street performer juggling daggers. Perhaps Vincent slipped down the tiny alley off Henrietta Street for a moment’s peace in the little garden of St Paul’s, ‘The Actors’ Church’.

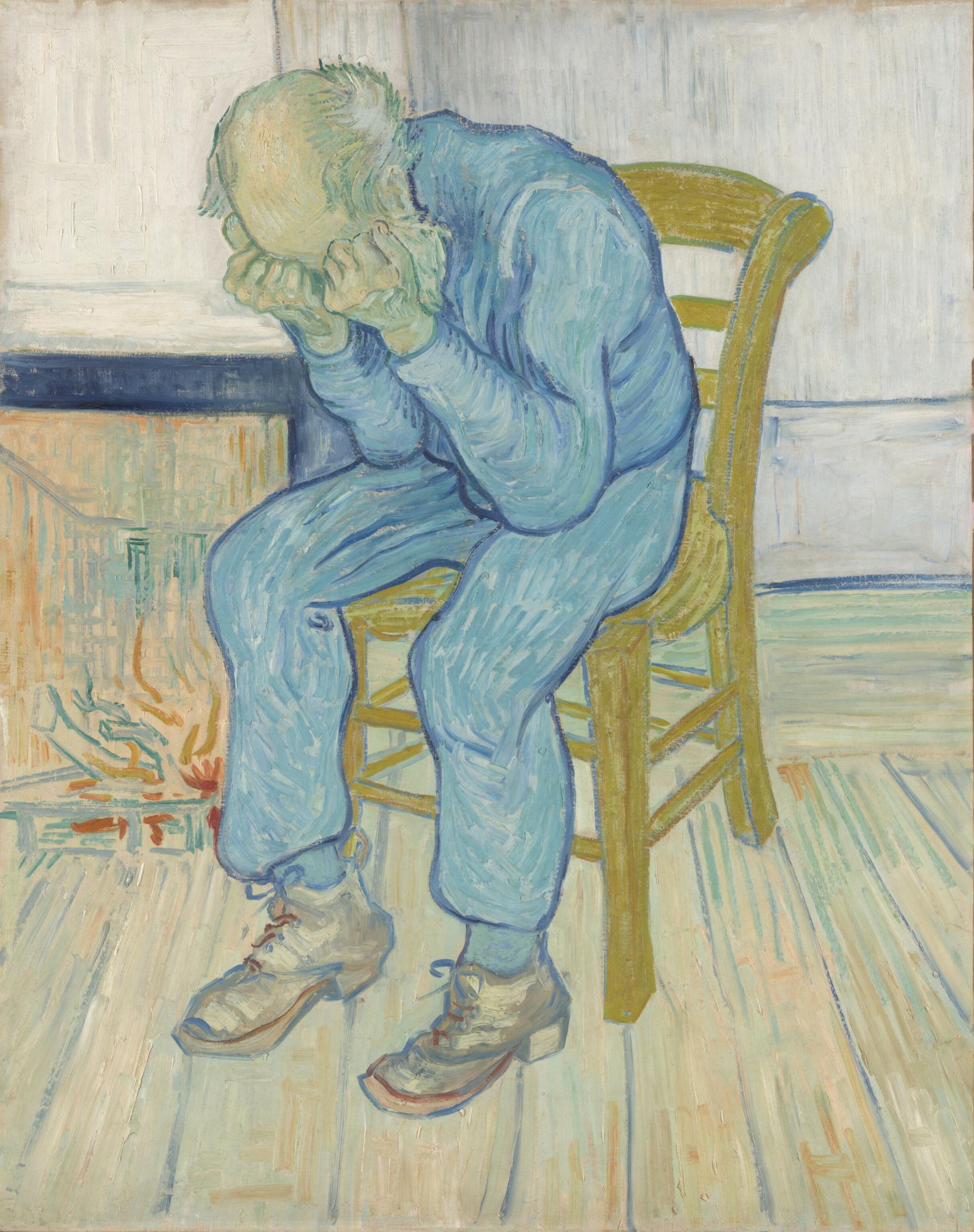

Van Gogh turned increasingly to religion during his time in London, seeing it as the answer to the social ills he saw around him. “He was politically quite naive,” says Bailey, but in London he developed an acute social conscience along with growing artistic awareness. The two merged in his future commitment to “art for the people” and his choice of artistic subjects. “He was at an impressionable age,” says Bailey, “and London was quite an education”.

Although he only lived in the capital for a couple of years, his time in the city clearly shaped him – and stayed with him – for the rest of his life.

Travel essentials

The Van Gogh and Britain exhibition takes place at the Tate Britain from 27 March-11 August 2019.

The Van Gogh House has tours from May/June 2019.

Living with Vincent Van Gogh: The Homes and Landscapes that Shaped the Artist by Martin Bailey is out on 25 April by White Lion Publishing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments