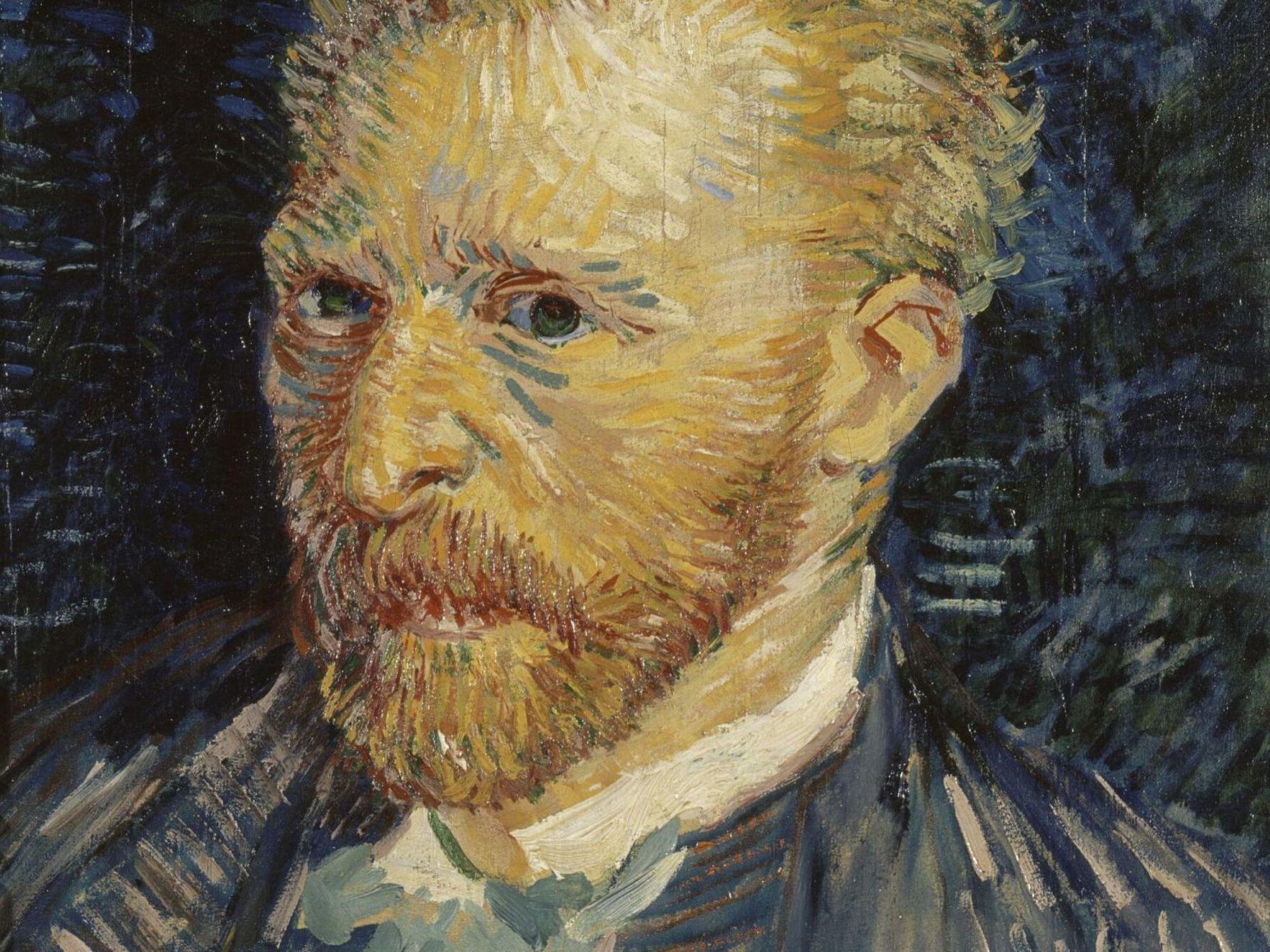

Portrait of the artist as a young man: Vincent van Gogh’s forgotten years in Britain

As Tate Britain celebrates the Dutch post-impressionist’s time spent in London, Alastair Smart looks back at an oft-overlooked period

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How much I love London,” wrote Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his brother Theo. Between the spring of 1873 and end of 1876, the Dutchman lived in the UK – mostly in the capital, but also for a while in Ramsgate. It’s not an especially well-known period of his life, but a major Tate exhibition, Van Gogh and Britain, looks set to change that.

The show will include 50 works by van Gogh, as well as others by 19th century British artists he admired (such as John Constable) and 20th century British artists he inspired (such as Francis Bacon). Probably the most important point to make, though, is that, in the mid-1870s, he wasn’t even an artist yet.

He moved to London from The Hague, aged 20, as an employee of the eminent art dealership Goupil & Cie. It was opening a branch on Southampton Street, near Covent Garden, and Van Gogh was sent over to work there as a clerk. It wasn’t until the turn of the 1880s – long after he’d left the UK – that he started painting. Which is to say, not a single canvas was created by the banks of the Thames or in his rented lodgings in Brixton.

What the exhibition offers is a portrait of the future artist as a young man. One who used to walk to and from work each day, his route taking in Westminster Bridge and the newly constructed Thames Embankment. At lunchtimes, the National Gallery was a haunt, while at weekends he wandered London’s “charming parks”. In a letter to Theo, he said: “I walk as much as I can… it’s absolutely beautiful here.”

He also had a liking for local fashion, specifically the top hat, insisting “you can’t be in London without one”.

Boasting a population of 4.5 million, the British capital was, in 1873, the largest city in the world: more than twice the size of Paris and almost 50 times bigger than The Hague. The American writer Henry James, who’d moved to London himself four years earlier, spoke of its “inconceivable immensity”. Victorian London has become synonymous today with soot, squalour and stench, yet that seemed to make little impact on Van Gogh, whose letters focus on his house with a “lovely garden in front” where he grew poppies and sweet peas.

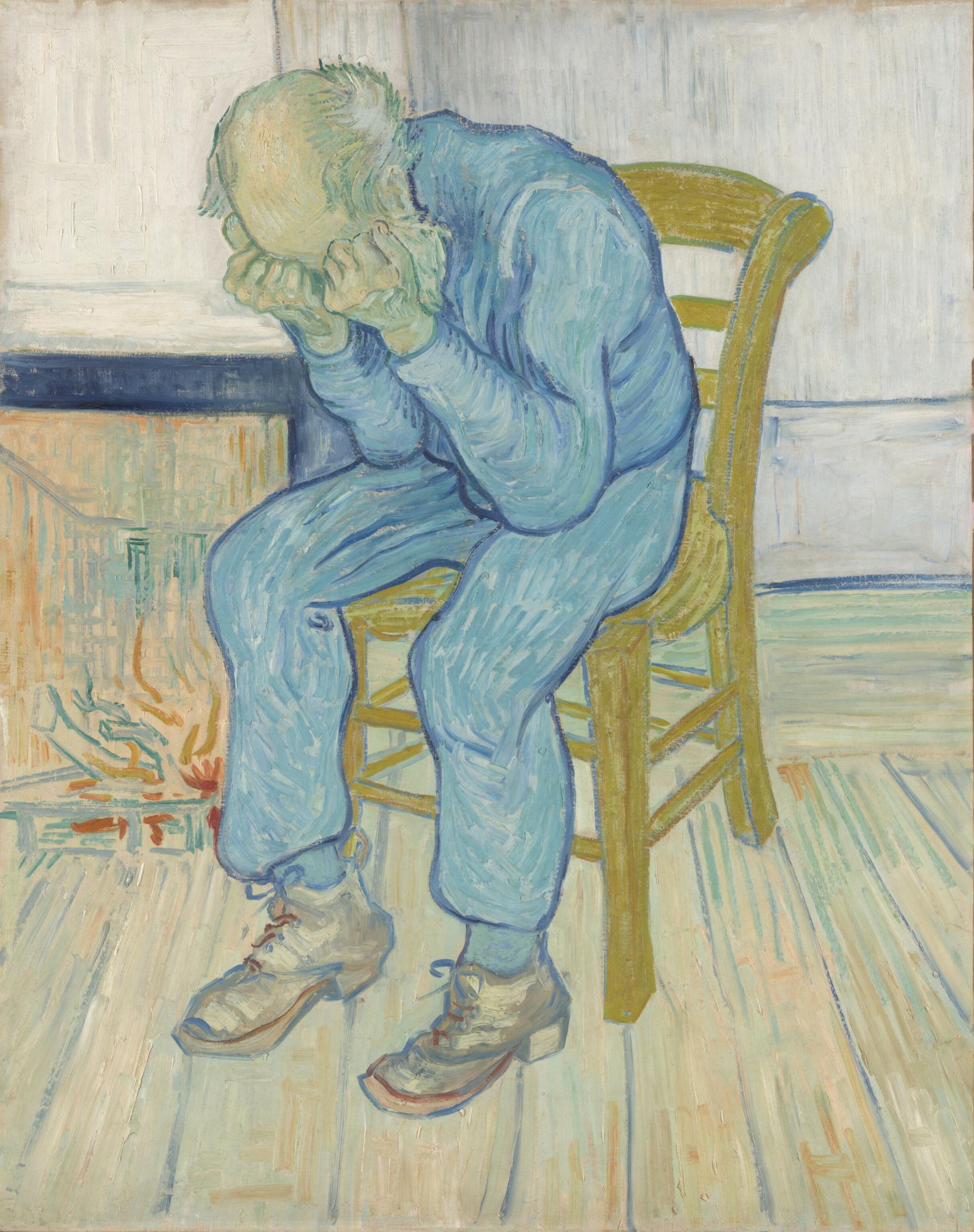

If all this sounds strangely positive for a figure we’ve come to associate with mental anguish, it’s perhaps no surprise to learn that the good times for Van Gogh didn’t last. In early 1876 he was fired by Goupil & Cie, following a series of tactless interactions with clients. There was upheaval, too, when he quit his south London lodgings in heartache, after the landlady’s daughter – with whom he’d fallen in love – married another tenant. (This domestic drama was the subject of an Olivier Award-winning play from 2002, Vincent in Brixton.)

Bouts of depression ensued, as did the occasional night sleeping rough and the painful search for a new profession. He’d go on to find work as an assistant teacher in Ramsgate and then Isleworth, but his heart was never in it.

Within a few months, he’d decided to become a preacher instead – influenced in part by the “extremely poor areas” he’d seen visiting London’s East End. His approach was ecumenical, rooted in comfort and consolation rather than Church dogma. He lapped up the writings of social reformers such as Thomas Carlyle, and Charles Dickens became a favourite author. (A love of Dickens would remain for the rest of Van Gogh’s life. His famous portraits of the café owner in Arles, Madame Ginoux, painted from 1888 to 1890, feature a copy of the Englishman’s Christmas Tales on the table before her.)

On 29 October 1876, Van Gogh stepped into the pulpit of Richmond Methodist Church and gave his first sermon. He deemed it a success and was soon writing to Theo that “if my lot is not to preach… then, truly, misery is my lot”.

As it happens, it was in Belgium – in the poor, coalmining district of Borinage – that his career as a pastor would, in the late 1870s, briefly take off. In December 1876, he took the boat to spend Christmas with his family in the Netherlands and chose never to return to the UK.

“The trend of recent exhibitions,” says Van Gogh and Britain curator Carol Jacobi, “has been to move away from the perception of the artist as a tormented genius and outsider, towards appreciating his engagement with the people and ideas of his time.” The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, for example, last year staged a show on the influence of Japanese prints on the artist.

Van Gogh was a worldly man, who “spoke French, German and English as well as Dutch”, says Jacobi. And “during his stay in Britain, he developed an interest in its culture born out of intellectual curiosity”.

What’s perhaps surprising is that it was the literary, rather than artistic, culture that excited van Gogh most. His letters make 100 (usually very positive) mentions of British novels and poems – by Dickens, Tennyson, George Eliot, Charlotte Brontë and others.

As for this country’s art, there’s a sense he never drastically changed the opinion he gave upon seeing 1873’s Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy: that it was, “with a few exceptions, feeble”. One notable set of exceptions were the print illustrations he saw in popular, current affairs magazines such as The Graphic and The Illustrated London News.

He said he liked their “virile” lines. Beyond style, however, it was their treatment of issues of social injustice (such as alcohol poisoning and unemployment) that appealed most. “The illustrations have the same sentiment as Dickens”, he said: “noble, healthy, and one always returns to them.”

Humility of subject matter would be mirrored in Van Gogh’s many future paintings of peasants and labourers. It’s probably best to avoid claiming the direct influence of London on the artist he’d become, though. Better instead to see those years in Britain as formative ones for Van Gogh the man, as the early twenties are for so many of us.

He experienced extreme highs and lows, the like of which would mark his entire adult life – and, as Jacobi points out, “London played a key role in forging his whole worldview”: one of sympathy for the downtrodden and dispossessed.

Van Gogh and Britain is at Tate Britain from 27 March to 11 August; tate.org.uk 020 7887 8888

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments