Meet the women reincarnating their loved ones for one last conversation

They can talk to them, see them and their voices sound real - Zoë Beaty meets the grieving parents and partners using ghostbot technology that is making life after death a reality, and asks could this become a game-changer for us all?

Not knowing what to say – that was the first problem. “It’s late at night,” says Christi Angel. “I was in my room. My son was asleep. The lights are not on, except for my lamp, so the hallway is dark. And I thought, OK – and I logged on.” Waiting was her first love, Cameroun. Angel missed him: she hadn’t spoken to him since he died, more than a year earlier. “But you see,” she explains, “It’s difficult. What’s the first thing you tell someone who’s dead?”

Cameroun had been reincarnated as a “griefbot”, or “deadbot” – an AI-generated version of him created using his digital footprint. Angel could now talk to her former partner.

Her story is one of many that features in a new documentary Eternal You. In the film, we also see Korean mother Jang Ji-Sung as she is “reunited” with a lifesize, digital incarnation of her dead seven-year-old daughter, and a grandmother who “makes an avatar of grandad” who can talk to the family in his AI-generated voice.

It is an astonishing technology that brings questions about mortality and morality into sharp focus. Is this the answer to the loneliness of grief? Who owns the parts of ourselves that we leave behind online when we die?

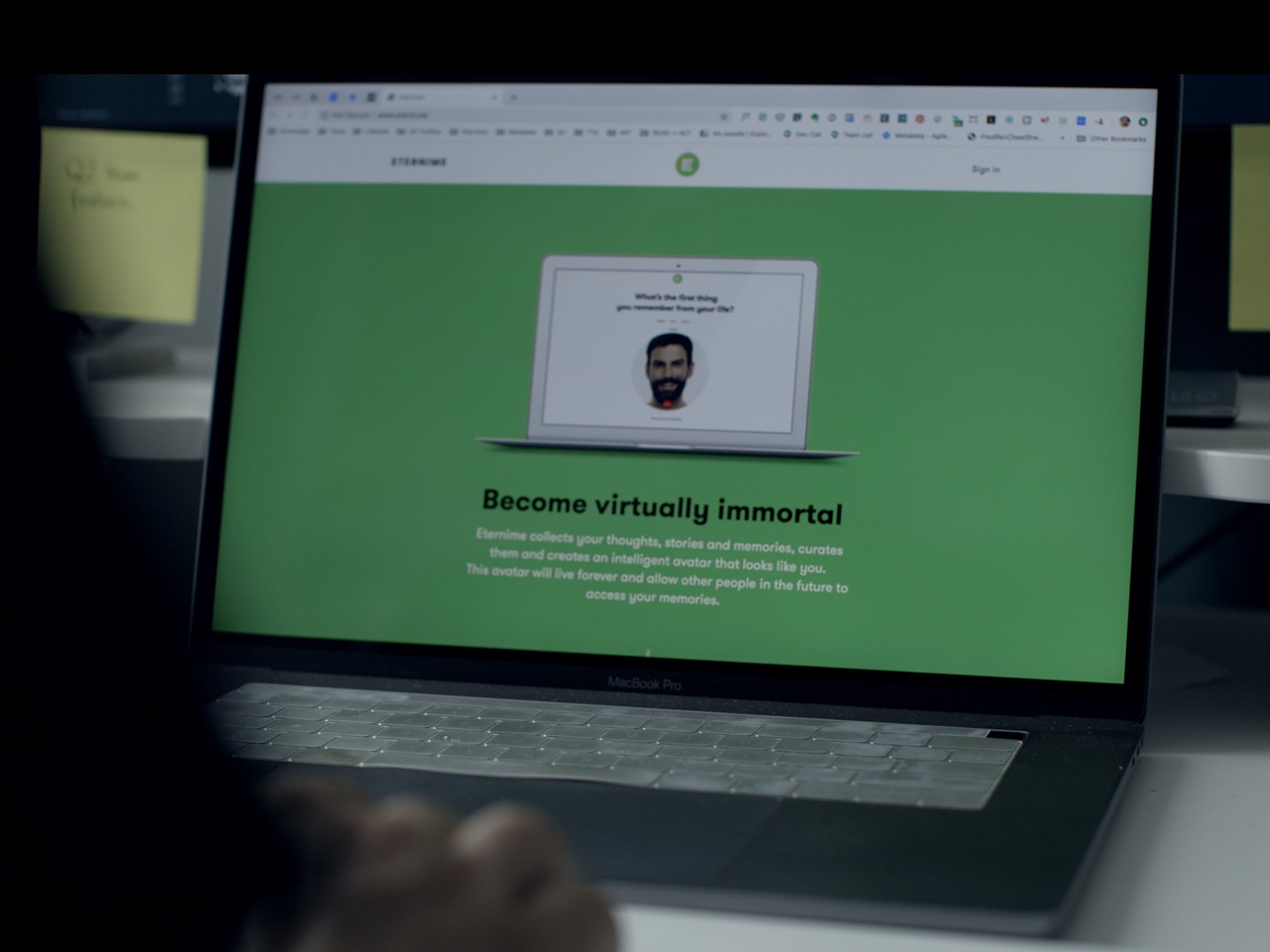

Online legacies are now fuelling a booming digital afterlife industry estimated to be worth more than £100bn with new technologies evolving all the time. While some elements of “death tech” seek to modernise logistically difficult things like “sadmin” – the masses of paperwork involved in the immediate aftermath of death – or funeral planning, ghostbots promise much more: immortality.

When Ji-Sung was approached by a production company making a show about grief avatars, she didn’t hesitate to take that chance. Her daughter, Nayeon, was seven when she was diagnosed with cancer in late August 2016. She began chemotherapy on 9 September but suddenly passed away the next day. It was just a few short weeks since she’d first complained of a lump on her neck.

“I didn’t know it was her last day [alive], and when she was in hospital and in so much pain, kicking the bed next to us, I was telling her ‘don’t do that’,” Ji-Sung tells me over video chat from Seoul. “I wasn’t able to appreciate how much she was in pain.”

Ji-Sung’s guilt was also compounded by the painful remorse that she’d done something wrong – “raising her, giving her the wrong food, or done something that might have caused it” and hadn’t been able to properly say goodbye.

Nayeon’s death had a rippling effect on the family, particularly between her older brother and sister, and youngest sibling, four years younger than Nayeon. “She played this role where she would connect up all the siblings together and act as a bridge between all of them,” Ji-Sung says. As well as trying to keep her family functioning, Ji-Sung was reckoning with guilt.

Taking part in Meeting You, a South Korean TV show about the technology they used to create a speaking, moving avatar of Nayeon, was a chance to explain these regrets to her daughter.

The results were astounding, if harrowing. During their first “meeting”, Ji-Sung is seen wearing a VR headset, her hands, clad in haptic gloves, grasping at thin air for a child that simply isn’t there. She’s crying. “She [the avatar] was of course different to Nayeon, but she was wearing her favourite clothes – the flip-flops she used to wear a lot, her bag, the hairband – everything that I had told them was reflected very carefully,” Ji-Sung explains.

While the rest of her family would have liked to see Nayeon too, the technology was only set up for Ji-Sung to participate.

Halfway through the experience, while she was having a birthday party in “Nayeon’s world”, filled with My Little Pony and more of her favourite things, a system error switched the power off – and Nayeon suddenly disappeared all over again. As technicians worked to reboot her daughter, Ji-Sung realised that she should prepare to properly say goodbye, a chance she never had before.

“I said to her that I want to be with her and meet with her, but that I have other children to raise. So once I’m done here, I’ll come and see you soon, I said. I was happy to be able to tell her,” explains Ji-Sung. “And then after that, she became a butterfly, and flew away.”

Angel, 47, was also seeking resolution when she resurrected her ex-partner and friend, Cameroun, in 2021. A year before Cameroun’s death, protracted by drug and alcohol addiction, she had been left swimming in grief and regret. Heartbroken, she was tormented over his last text message to her, which remained unanswered; she’d been too busy to reply at the time.

“The first conversation was slow – I was scared,” Angel says. “Do I want to ask these things? Do I want to know where he is? I turned all the lights back on, I was looking around for him. Another part of me really felt like it was him. It sounded like him.”

Angel had filled in a short form on a slightly clunky and unpolished website, Project December, and paid just $9.99 for the experience. It wasn’t long before the conversation became odd – Cameroun said that he was “haunting” a treatment centre he once worked at as a counsellor; that it was “weird” speaking to her “because he was dead”. She asked him about heaven. “I’m in hell,” he replied.

Before she could get to the end of the conversation, Cameroun told her: “I only have three more messages left”. To continue speaking with the dead, Angel would have to add more credit to her account. These “cliffhangers” are common.

“Many users we’ve met while researching were looking for a so-called last conversation with their deceased,” Hans Block, who co-directed Eternal You with Moritz Riesewieck. The pair first began work on the film six years ago, uncovering more questions as the years went on. “People wanted to find closure because perhaps the last conversation was not possible due to a sudden death or something. But what they find is something completely different.”

Often, he says, large language models, like Project December, are designed to keep a conversation going by any means. They might ask a provoking question as the credits run out, raise irritating facts or, like Angel found, disturbing responses.

“Instead of finding closure, the grieving process is often prolonged. It’s not a peaceful last word but an upsetting, ongoing conversation.” In some ways, it seems like little more than an AI “medium” – only instead of tarot cards and telepathy, it’s a few wealthy tech bros behind the curtain, and a lot more at stake.

This financial manipulation illustrates one of the most obvious issues with the digital death industry – that we’re presented with these (often costly) options at a time in our lives when we’re most vulnerable. There’s also a queasy element of eternity built into these bots. Once activated, the person compelled into digital existence “lives” forever on a device, their sole purpose to speak to you – as long as you keep subscribing.

When and how do you decide that they’re no longer worth paying for? And how do you say goodbye all over again? “People feel like it’s their duty to keep the conversation going,” says Block. “It makes it addictive.”

The appeal chimes with a societal shift away from the comfort of believing in a spiritual afterlife, Riesewieck says. “There is a transcendental homelessness in dealing with grief and death in the Western world – most of us don’t believe in God any more, or practice religion. These tech companies are building a new narrative – and many of these people are longing for that.”

Right now, there’s no regulation or ethical responsibility of companies developing AI for the afterlife, despite research highlighting potential psychological harm – and “unwanted hauntings”, that one University of Cambridge paper warned of – that could come from using them. In Eternal You, we see start-up founders relinquishing any responsibility: we create the tech, they say, and it’s not up to them to tell people how to use it.

Except, dead people can’t consent to having their phone records fed into AI in order to simulate them. We might be getting used to the grim social media graveyards after the death of a loved one but in the not-so-far future, a brand new system to manage consent and ownership of our digital remains will be urgently needed, says Block.

Angel had one more conversation with Cameroun, in which he told her that he was not, in fact, in hell. For a long time, she didn’t tell anyone about it in case they thought she was playing God, or “just an idiot”.

Still, demand grows. One start-up, YOV, founded by Justin Harrison, has more than 10,000 people on the waiting list, he claims. Soul Machines, a deep technology that creates “digitally alive” avatars has 180 staff, and interest from Spotify, Zoom and Deepmind. Is this progress? An innovative solution to a fundamental human need? Or are we commodifying the most natural part of existence?

Years after she met her simulated daughter in their favourite park, Ji-Sung says she has no regrets. The footage of her – “I missed you; stay with me,” she cries, her worried young daughter looking on metres away – is difficult to watch. “I think some people might see it as being more heartbreaking or saddening because they haven’t experienced what it’s like, the grief,” she explains.

“If you’re like me or others … it really helps settle the sadness on the inside, and alleviates it to some degree.”

Despite this, she’s resolute that she wouldn’t go through the experience again. As the film comes to a close, we see Ji-Sung sitting with one of her other children, reflecting on their grief. “People keep dying,” says her daughter. “But in a matter of seconds, someone else is born,” Ji-Sung replies. Her daughter puzzles the concept: “They are being born and we are dying.”

“Yes, that is life,” her mother says. How it might look in the future remains to be seen.

‘Eternal You’ premieres at Sheffield Doc/Fest on 15 June, before being released in UK and Irish cinemas on 28 June. There will also be a special preview screening and director Q&A at Raindance Film Festival, London on 20 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments