Is there ever a right time to return to work after a bereavement?

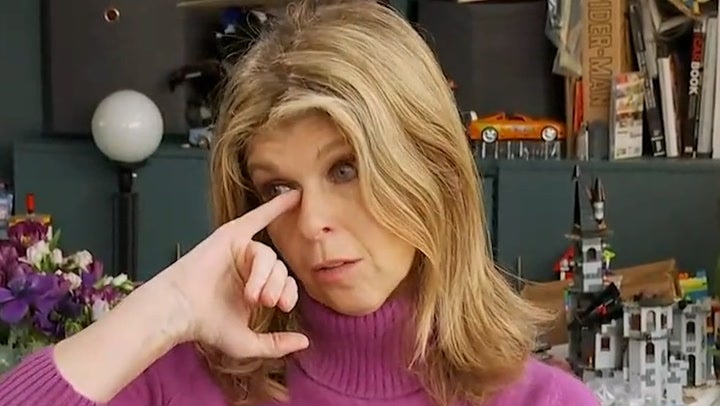

As TV presenter Kate Garraway returns to her role on ‘Good Morning Britain’ after the death of her husband Derek, Zoë Beaty, who was bereaved last year, looks at whether going back to the day job helps or hinders when someone is grieving

The thing is, it’s just really hard to know what to do with yourself, isn’t it?” Sarah asks. It's been exactly three weeks since her dad passed away, and two weeks and six days since she returned to work. For the 24 hours she took off in between, she says, “I just watched dreadful Netflix shows to be honest. I went back to work the next day. I needed a distraction. A semblance of normality. I can’t remember a thing about those next few days.”

Sarah, from London, who works in marketing, lost her Dad a year after he was diagnosed with dementia. The decline had been slow at first, then suddenly imminent: “We got a call on the Sunday before he died to say he had significantly deteriorated, and by Tuesday he was gone.” It was hard to make sense of it, she says, despite the death being somewhat expected. “Everyone at work keeps asking, ‘why are you here?’. It feels a bit like a judgement, but right now, I don't know how I feel.” Sometimes the only thing to do is what you know.

This week Kate Garraway spoke publicly for the first time since the death of her husband, Derek Draper – who died last month after living with extreme complications from Covid. She said her family’s “emotions are at 110 per cent” following his funeral on Friday. On Thursday, she’ll return to her role presenting ITV’s Good Morning Britain.

For anyone who has navigated illness, death, grief and being subsequently thrust back to the living world there is always a question over when is too soon to return. “Life has to start,” Kate said. “We have to pick ourselves up and go on. That’s what Derek would want me to do.”

It’s a looming question over anyone experiencing someone dying – how do you let your colleagues know that life has violently, irrevocably changed? When my stepdad died in February last year, I don’t remember telling anyone in my working life, though I must have done. I was generously given two weeks’ compassionate leave from my part-time contract, at which point there would be a review to see if I was “ready” to return to work. I said I would be.

Despite there being a very valid reason for significantly relegating work down my list of priorities for the next year, I was embarrassed: I had coasted, missed good opportunities and lost my work ethic. “I heard myself apologising to my boss when I phoned her to tell her dad had died,” Sarah says. I understand that feeling of letting people down. Death brings out a complicated swirl of feelings, a renewed sense of motivation to make the most of life, and what we have – or a thinly-veiled attempt to ignore what’s really going on...

What is certain is that there is no one right way to react. Grief looks different in every house and every head. “We all have our different versions of it,” says Andy Langford, clinical director at Cruse Bereavement Care. “For some of us, we need a little bit of time off to work through some logistics and then we're generally okay. But others need a different approach.”

Stacey Heale had been working in the echelons of academia as a fashion lecturer when her husband Greg was diagnosed with terminal bowel cancer five years before his death in 2021. “Before my husband died, my job had been more or less my entire identity,” she explains. “It was a tough job as a course leader but something to be proud of, even though, when I thought about it, it often made me unhappy. He was diagnosed on our second child’s first birthday, I was just finishing maternity leave. We were in A&E and I just thought, oh my god, this is it. And then, the only thing that matters is people.”

Stacey took voluntary redundancy and essentially became a full-time carer to her husband and two children. “After he died, I just had this realisation of being a sole parent – it was just this terror, of being so aware that everything is on you and that will be the case forever. I needed to work to support us financially, but I also needed to relocate myself and map out our future, whatever that might look like.”

It’s particularly cruel that death brings not just grief but a gnarly and often distressing aftermath of finances to unpick. Garraway said last year it had been “tough” financially as she needed to meet the costs of enormous caring overheads and provide for the family as a lone working parent, but also take time off work too to look after Derek.

There’s no legal right for bereavement leave to be paid, apart from in the case of parental bereavement (two weeks). Those who have lost partners are entitled to a lump sum payment of £2,500 and 18 monthly payments of £100, or £3,500 lump sum and £350 payments if they’re responsible for a child under the age of 20. It’s a help, but it’s unlikely to go far.

There’s this sense that, because I just took one day off, that’s me done. I don’t know how it would be if I told them I need time after that – it’s like the box has been ticked and now I should be fine. But it doesn’t work like that

Still, for Stacey, however, returning to work brought other benefits. “It was actually really, really nice for me to go back to work, because I just wanted to be me again,” she says. She also needed to move out of a house the family had long outgrown, though says that she still can’t get a mortgage because she’s a sole parent of two, despite now being financially stable.

“I felt like I had lost so much of myself in terms of not having a real purpose. Not having anything that was just mine. It actually felt like a bit of a holiday, because everything I had been doing at home was so hard and bleak.”

It was also the case that after a long illness she had grieved her husband long before he’d died. “I was grieving my relationship, my husband, my old career, and my past self in so many ways”, she says.

But while some may find work helps them emotionally, the impact of what has happened to them should not be underestimated and this can play out in a number of ways that can affect our performance. “We can each experience bereavements quite uniquely, but it’s common to find some aspects challenging,” says Langford. “Processing information involves quite a lot of cognitive work and it can be quite impeding when we’re grieving.

“So it’s not unusual to find that people go back to work – or, even before then when you’re trying to sort out executor information like banking details – for the person to really struggle, or find simple things really difficult to work through. Our bodies and our brains take on so much by the process of grieving.”

“It can be awkward,” says Sarah, “not just in trying to communicate what you can manage, but also in how people react. Some people give you advice that you haven’t asked for; others act like nothing has happened, which is just as strange.” For someone like Sarah, who is very much at the beginning of her grieving process, there have been other obstacles. “There’s this sense that, because I just took one day off, that’s me done,” she adds. “I don’t know how it would be if I told them I need time after that – it’s like the box has been ticked and now I should be fine. But it doesn’t work like that. I needed work for that anchor and routine, but I do worry.”

It’s very difficult to tell your boss, eight months after someone you love has died, that you messed up a presentation or forgot an important email because you’re still grieving and expect them to take it at face value. It’s something Langford is trying to get more understanding around. “We've certainly worked with organisations or individuals where issues have been flagged up around performance, or people going off sick a lot. But actually, when you look at it, they’re experiencing grief.

“And if that's managed in a sensitive way, with some open conversations, clear lines of communication – of knowing when to share that things are feeling difficult, for example – and some planning and review, neither the individual or the organisation need to go through the pain of all of that.”

For people like Stacey – and Garraway – work must also fit around managing the added heartbreak of seeing children grieve, too.

“It is full-on,” says Stacey. “When Greg died they were five and seven. So now it’s almost like they’re waking up to the realities of losing their dad. And that comes out in lots of different ways; it’s not like dealing with adults who might be able to sit down and explain why they’re sad.

“In one kid it’s absolute meltdowns, like catastrophic anger and frustration. In the other it’s tears, crying, difficulty sleeping. It’s hard. I’m the only one here – the only one at home to talk to them about it. The emotional side of it is so prevalent in the house.”

Since her husband’s death, Stacey has thrown herself back into work, but with a different attitude and purpose. She’s written a book – Now Is Not The Time For Flowers – which is out in March this year, and is no longer hungry to tackle the steep ladder of a career in academia, but to concentrate on what she's learnt from the loss of her husband. She says that she’s found solace in finding others in her position too. “There’s a real, deep understanding between people who have lost their partners,” she says. “And a renewed sense of what’s important.”

If you are bereaved and need support call the Cruse Bereavement Support helpine on 0808 8081677

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks