A stitch in time: the strangers taking on unfinished knitting projects for grieving families

Caitlin Huson meets the volunteer ‘finishers’ completing labours of love after their makers pass away

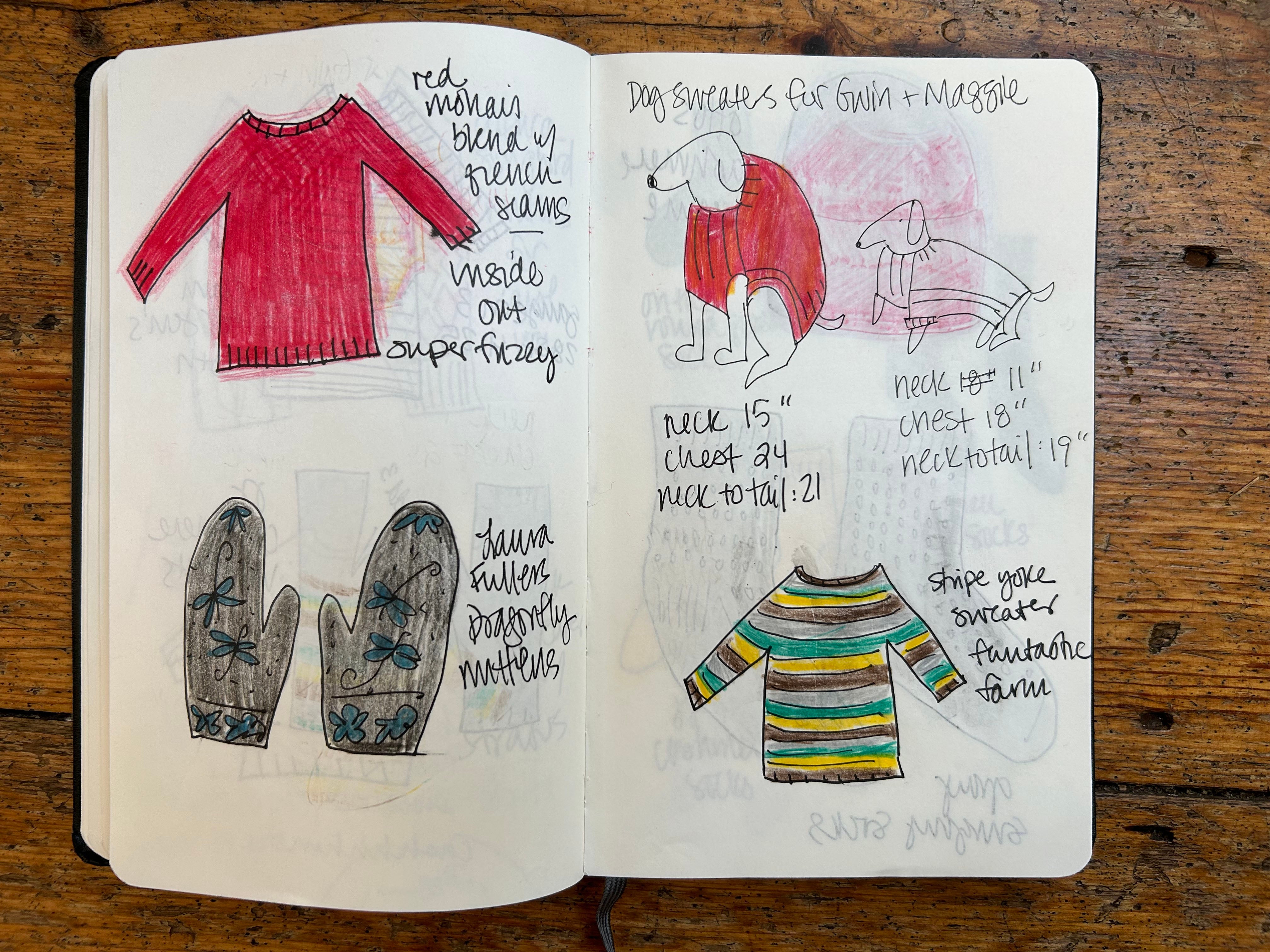

Karen Sturges was knitting five baby sweaters, one for each grandchild’s future baby, when she was suddenly diagnosed with lymphoma. She did not have much longer to live.

As she dealt with the devastation of the diagnosis, one thing kept coming up.

“The thing that she was most worried about was finishing these sweaters,” says her daughter Annie Gatewood, 53. “She was just distraught that she didn’t think she was going to be able to finish.”

Sturges worked on them until four days before she died in 2021. Gatewood and her sister held on to the two remaining unfinished sweaters, not sure what they would do. Neither one knew how to knit.

Then in the late summer of 2022, Gatewood, who lives in Harpswell, Maine, was matched with a “finisher” in Portland, Maine, called Sarah deDoes – now one of more than 1,000 volunteers who complete unfinished fiber arts projects for grieving loved ones through a group called Loose Ends.

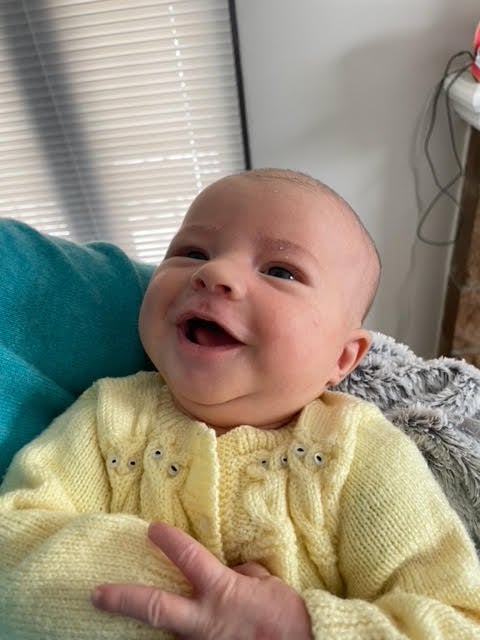

DeDoes finished knitting the two tiny sweaters, then handed them off to Gatewood in late October. The two met at DeDoes’s home in Portland.

“I saw her and burst into tears, because she looks like my mom,” Gatewood says, explaining their similar look and manner, and that they were both of Danish descent.

The sweaters – soft, white acrylic wool with little owls across the front – were expertly knitted.

I couldn’t help but think about how I would feel if I couldn’t finish a project and someone was willing to take it over

“We know for sure my mom would have been just delighted,” Gatewood says.

A lifetime knitter, DeDoes, 86, says she took on the project because she understood the importance of it.

“Because of my age, I feel more closely involved in how a family would feel. I can sort of put myself on the other side,” she says. “I couldn’t help but think about how I would feel if I couldn’t finish a project and someone was willing to take it over.”

In fact, those sweaters inspired DeDoes to start her own project for future great-grandchildren. “I just feel comfortable now knowing that if I can’t finish it then someone else will.”

The growing roster of Loose Ends volunteers is made up of crafters from around the world with diverse fiber arts skills ranging from quilting to amigurumi.

It was started in September by friends Masey Kaplan and Jen Simonic, who like to call themselves matchmakers.

Kaplan, 53, of Falmouth, Maine, and Simonic, 52, of Seattle are avid knitters and know first-hand what it’s like to have friends reach out about finishing a pair of mittens or a scarf or some other handmade item left behind by deceased loved ones. And they know first-hand just how much time and care it will take to complete.

“Making something with your hands for someone is an expression of love,” says Kaplan, “and when I finish things and give them to people, I want them to know that I love them, and I was making this especially for them. I want them to feel that.”

It is that feeling that drove the longtime friends to create the Loose Ends website, and put a call out for volunteers and unfinished projects. The projects must be left behind by a loved one who is deceased or unable to complete the handwork due to illness or disability.

There is no payment to have a project completed. The only cost is postage, though with more and more volunteers joining, Kaplan and Simonic are often able to make local matches, so postage is not necessary.

“We’re connecting projects to a stranger who feels the same way, who will complete that gesture of love for another stranger,” says Kaplan, “so that the person who is grieving will get to experience that feeling we [crafters] know is important.”

As soon as Eugenia Opuda, 33, of Portland, Maine, heard about Loose Ends, she signed up as a finisher.

“I love that name,” Opuda says. “It just sounds so dramatic like a superhero. ‘The Finisher!’”

She is crocheting a large navy blue blanket for someone in Portland, Oregon, whose mother passed away.

The blanket was one of three the mother was working on throughout her cancer treatments, and although the stitches are inconsistent, the children wanted to keep every stitch their mother made.

Knowing that even through her illness and all the pain and challenges, she still managed to make so much progress, I didn’t want her kids to lose that

“They didn’t want to lose that piece of their mom when she was working on it at the hospital,” says Opuda, so she added a stitch marker to the blanket to show where her stitches began. That way the family would know which part of the blanket their mother’s hands had touched.

“Something that non-crafters don’t really know is just how much time something takes, especially like a blanket. And knowing that even through her illness and all the pain and challenges, she still managed to make so much progress, I didn’t want her kids to lose that.”

When the blanket is finished, Opuda says the only thing she hopes the recipient knows is just how much their mom loved them.

The tenderness finishers have for the project holders is what creates such meaning, and that – for Kaplan and Simonic – is the most important part.

“The thing that connects [the finisher and the project holder] is this handmade object, and somebody’s ability to say in their grief, ‘Hey, I need some help finishing this’, and somebody’s ability to say, ‘I can fill that blanket-shaped hole in your heart right now,’” says Simonic.

“It’s the reverence held between the crafter who understands it, and the person who is living with grief, whether it’s been 24 hours, two months or 40 years,” says Kaplan.

This deep respect for another crafter’s work is what motivated Valerie Thornburg, 37, of Lynden, Washington, to persevere with the project she volunteered for. The project holder told Thornburg his wife had been learning to knit and had been knitting through medical treatments until she no longer could.

“She intended to make this scarf for her husband, but there were different plans for her life,” says Thornburg.

There was no pattern in the package of materials left behind, so it took Thornburg some time researching patterns and learning new stitches to replicate the work.

“You have thousands and thousands of stitches that pass through your fingers, and a lot of love goes into each of those,” says Thornburg. “You can see she was a newer knitter and she was learning. I just think of all that love in those stitches that aren’t perfect.”

In knitting, there is a term called lifeline, which is when a piece of yarn is threaded through a row of stitches as a preventive measure so that if you must unravel, the stitches are kept safe. Thornburg has been knitting for 18 years and doesn’t use lifelines anymore, but she made an exception for this project.

“I can’t lose her stitches. The most important thing for me is that I’m able to keep her work exactly as it was.”

You don’t know what someone’s going through on a day-to-day basis, but I do know these little acts of kindness make people realise there are people out there willing to help

Thornburg’s plan is to mark the lifeline in the scarf in a more permanent way. She has a few ideas and will run them by the project holder so he can choose, but, she says, “Perhaps a little red heart will do.”

Kaplan and Simonic say their hope is that not only do more volunteers sign up, but that more and more people submit unfinished pieces to Loose Ends.

For Gatewood, giving her late mother’s knitting project to a stranger was a bit unnerving. But in retrospect, she says, “I had to give up and let go, which was, in and of itself, a healing thing. And then it came back to me 100-fold.”

Volunteer finishers are in 23 countries and counting, and they represent a wide range of ages, religions, nationalities and political affiliations. The common thread, according to Kaplan and Simonic, is empathy and extreme generosity.

“We all experience pain, and we all experience grief,” says Simonic. “You don’t know what someone’s going through on a day-to-day basis that’s going to make them give up, but I do know these little acts of kindness make people realise there are people out there willing to help.”

“It’s a hurting and divided world,” says Kaplan, “and this is a tiny way to start to mend it.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments