Solar storms: From farmers to flights, how space weather is messing everything up

While they caused the recent northern lights spectacular, increasingly powerful sun events could have far-reaching consequences for our infrastructure. Are we about to witness a repeat of the ‘Carrington Event’ which caused chaos over 100 years ago and could pose a bigger danger today, asks Anthony Cuthbertson

In September 1859, two telegraph operators 100 miles apart turned off the power to their stations to wait out a period of unusual electromagnetic activity. For the next two hours, to their astonishment, they continued their conversation using solely electrical current that had travelled through space from a sunspot 150 million kilometres away. It was the most intense solar storm in recorded history, and while it enabled the first ever solar-powered communication, it also proved so strong that some operators received electric shocks. Sparks shooting out from telegraph poles even reportedly caused fires, in what would later be remembered as “the week the sun touched the Earth”.

The Carrington Event, as it officially came to be known, caused auroras to be seen in the sky as far south as Mexico as a massive coronal mass ejection (CME) from the sun smashed through the Earth’s magnetosphere. The northern lights wouldn’t be seen that far south again for another 165 years, when a category 5 geomagnetic storm lit up the skies across Sinaloa and Chihuahua on 10 May 2024.

There were no telegraph networks to disrupt this time, but the radiation emitted from the solar active region known as AR 13664 was extreme enough to cause other terrestrial problems. Qatar and Emirates flights were forced to change their routes to avoid the worst geomagnetic storms at the poles, while farmers across Canada and some parts of the US experienced malfunctions with their equipment following a GPS blackout.

A storm of any greater magnitude is capable of impacting not only flights and geopositioning satellites, but entire electrical grids. It could impact communications and critical infrastructure, causing chaos orders of magnitude greater than the Carrington Event. And while it may seem like a once-in-several-generations event, the current period of solar activity may not yet be over. With the return of the AR 13697 sunspot this week, some space weather experts are warning that even more severe solar storms could be on their way.

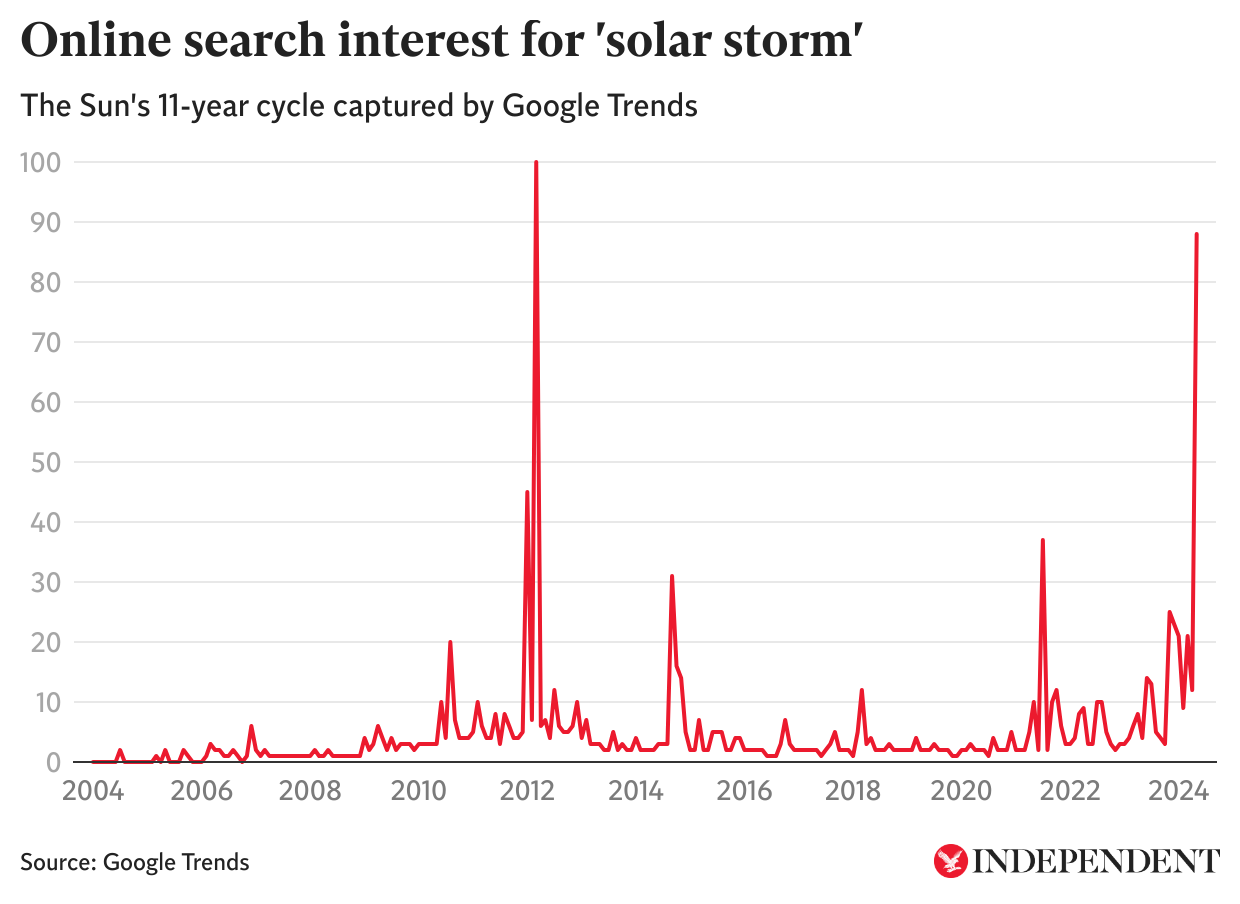

The sun is currently approaching the peak of its 11-year activity cycle, brought about by its north and south poles switching places as its magnetic field completely flips. It can be measured by the rise and fall in the number of sunspots and dark regions of concentrated magnetic fields visible on the star’s surface. (These days, the solar cycle can also be tracked by the number of web searches for terms like “solar storm” through Google Trends.)

The last peak, or solar maximum as it is known, took place in April 2014, slightly later than originally forecast. The solar minimum, when sun activity is at its lowest, then took place slightly earlier than expected, in December 2019. It has been gradually increasing ever since then, with a spike in mid-May.

“The maximum of this solar cycle is predicted to be around July 2025, although scientists will not know that solar maximum has occurred until after the peak,” Dr Steph Yardley, a solar scientist from Northumbria University, told The Independent.

“Given that the solar minimum was earlier than expected, the same may be true of solar maximum. While the aurora can occur at any time during the solar cycle, displays are more frequent and often stronger during solar maximum.”

Beyond this rough guideline of activity offered by the solar cycle, predicting solar storms is notoriously difficult. The UK is one of the pioneers when it comes to space forecasts, having set up one of the world’s first automated real-time systems for the 24/7 monitoring of satellite images for extreme solar flares.

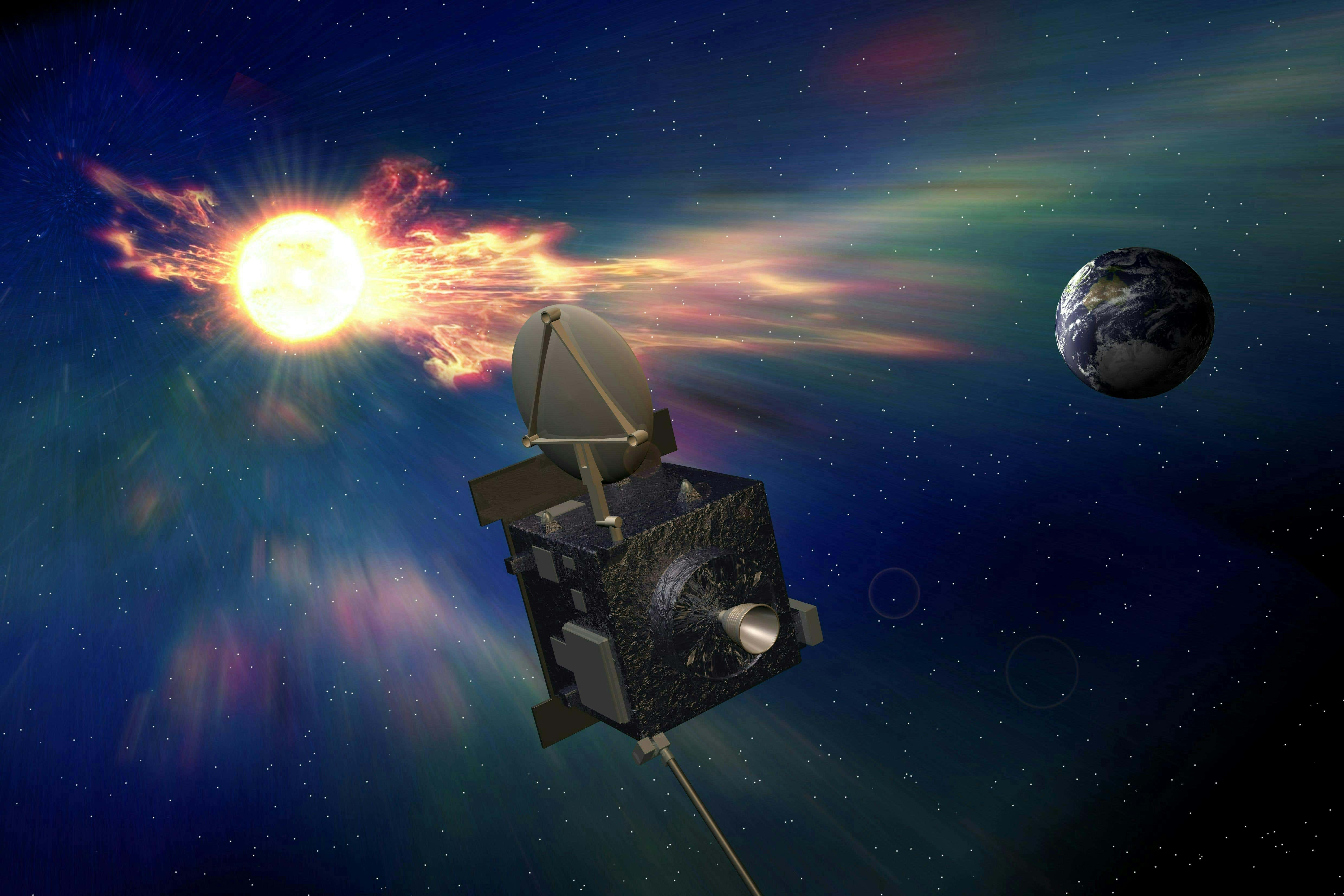

Led by Professor Rami Qahwaji at the University of Bradford, the Space Weather Prediction Group initiative works with Nasa’s Solar Dynamics Observatory satellite to process the latest images in an effort to predict severe solar storms.

According to Professor Qahwaji, the solar maximum has already been reached, and the next few months will bring an intense period of activity.

“Our system successfully predicted the latest solar storms, which produced the northern lights seen across the UK,” he said. “We are now going through the solar maximum. Initially, it was predicted that the solar maximum would be in 2025, but it seems the sun has reached its peak earlier than expected.”

The latest forecast from the Space Weather Prediction Centre in the US suggests solar maximum will take place between January and October of this year, with the number of sunspots peaking at between 137 and 173 – much higher than the 114 sunspots recorded during the 2014 maximum.

In May, the UK Space Agency announced that Europe’s first operational satellite to spot solar storms will be built in Stevenage, which will significantly boost our ability to forecast serious space weather events. It could provide vital extra warning about potentially disruptive storms, giving notice of four to five days of solar winds streaming toward Earth.

The advanced warnings will give time to prepare for the impact of the solar storm. Vulnerable devices could be unplugged or grounded, while power grid operators could ensure that the current is sufficiently regulated so that any additional input will not overload it.

As the solar region responsible for the latest activity rotates to face the Earth once again, more storms may soon be on their way.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks