‘Every kindergarten is a grave’: Survivors of Mariupol siege reveal the darkest horrors of Putin’s war

Tens of thousands of people are trapped in the besieged Ukrainian city of Mariupol, which has become a grim symbol of Russia’s brutal conflict. Those who fled to nearby Zaporizhzhia tell Bel Trew about the starvation, slaughter, and graves being dug across parks, gardens, and schools

The sandpits in the kindergarten playgrounds of Mariupol are now mass graves, because soft soil is quicker to dig when burying corpses under relentless shelling.

The residents of the besieged city have no time to properly lay the dead to rest – or bury whatever remains of them – lest they become the latest victims of Vladimir Putin’s brutal invasion.

And so the abandoned play areas, mauled by war, have become a different kind of resting place.

These days every sandpit, cratered park and communal garden wedged between the bombed out ribcages of buildings in the port city has become a makeshift cemetery.

“One rocket took out a nearby residential building with 20 people inside. People were trying to pull out the bodies with their bare hands, when another rocket landed on top of them,” Alisia, a mother-of-two, tells The Independent after escaping to the relative safety of Zaporizhzhia. It is a city 200km north of Mariupol that is itself on the edge of a moving frontline.

“I saw so many bodies, no one was able to pick all of them up. People are burying them in the sand pits on top of each other,” the 35-year-old adds shakily as her daughters, dressed in matching pink hoodies, tend to their terrified cat behind her. “Grave digging is extremely dangerous.”

Sitting in a supermarket complex turned makeshift reception centre for arrivals from Mariupol, Alisia is relieved to have fled the city where more than 100,000 people are still estimated to be trapped amid incessant Russian shelling.

A few thousand people have managed to escape by their own means – by car, on foot or even by bicycle – in recent days, but multiple efforts to secure a humanitarian corridor and organise evacuation convoys have failed.

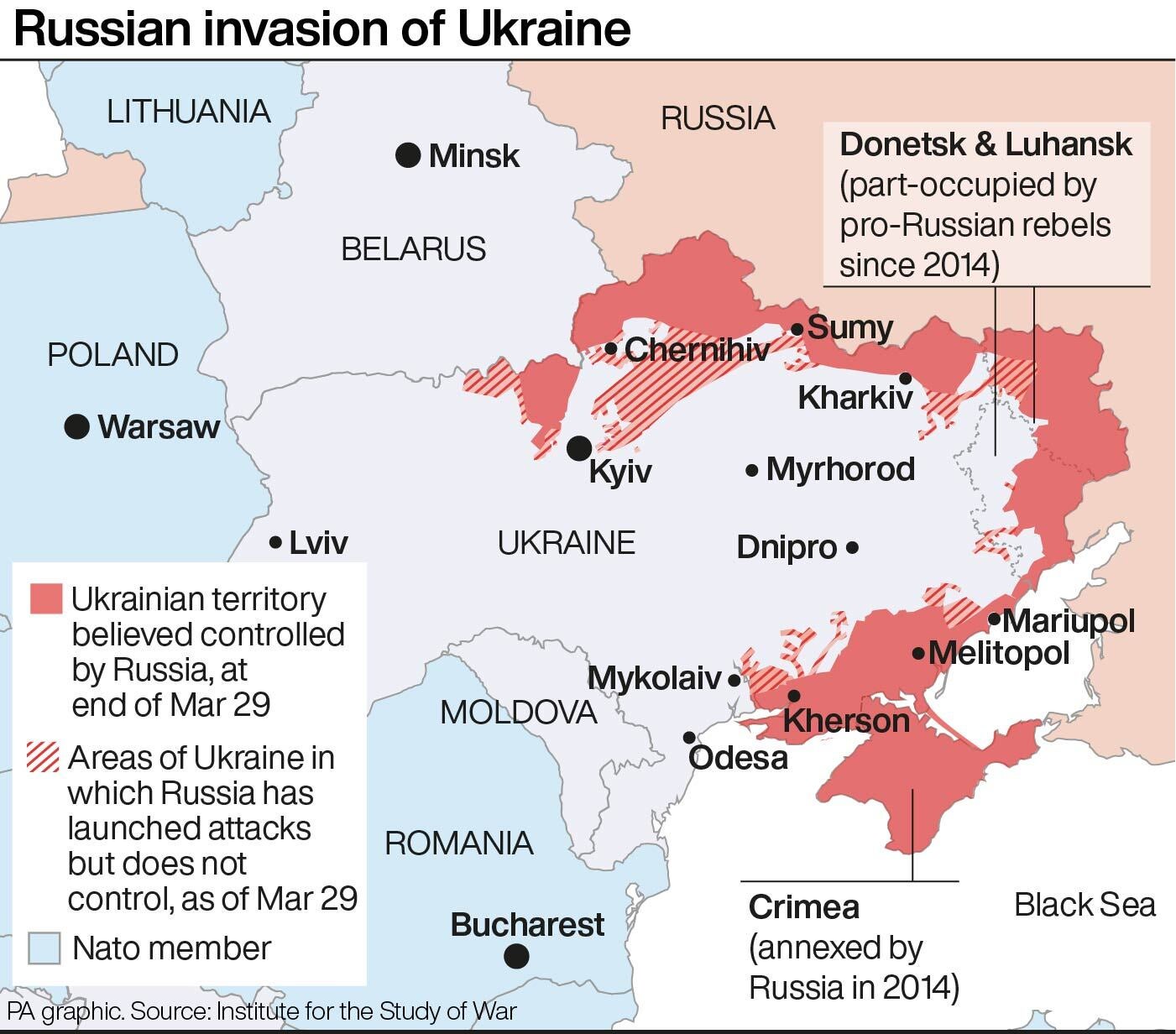

Mariupol, a strategic port and land bridge between Russia and Crimea, which Moscow annexed in 2014, has become synonymous with the brutality of Putin’s invasion. The city has suffered the worst of the bombardment, and has been under constant siege for more than a month.

It is a genocide against the inhabitants of Mariupol

Half of Alisia’s family are missing as they were separated when the frontline engulfed their neighbourhoods in early March.

She finally had to leave them when their supply of food and water, gathered from melting snow and rainwater, ran out.

“We were constantly underground for the last two weeks before we left. I didn’t see the sun,” Alisia says, swallowing her words with a pause.

“We had one sack of potatoes left to eat. We found ourselves in no-man’s land and had to run.”

‘Everyday life in Mariupol is digging a grave for someone’

Alicia’s account was echoed by two dozen other Mariupol residents The Independent has interviewed over the last week, who also spoke of mass starvation, mass slaughter, and mass graves.

Alia, 20, and her boyfriend Max, 21, both students, say the missile fire was so intense, it took them two attempts to escape.

The first time, the young couple were offered a lift from a family friend who had managed to find a working car, but was killed in a bomb strike as he drove to pick up them up.

The second time, relatives from outside the city drove through Russian-occupied territory and navigated the fighting to retrieve them. But Max’s and Alia’s parents are still stranded in Mariupol, having given up the precious places in the car for their children.

“The corner of every kindergarten is a grave. We had 15 bodies buried in the garden next to our building,” Alia says, holding her cat, who is wrapped in a Christmas blanket.

“Everyday life in Mariupol is digging a grave for someone,” adds Max, ashen-faced.

Russia has denied targeting civilians in Ukraine since Putin launched on 24 February what he has called a “special military operation” aimed at “de-nazifying” the country.

But witness testimonies from Mariupol paint a picture of savage attacks that appear indiscriminate at best, and retributive at worst.

The accounts and evidence are so harrowing that Amnesty International, which documented the use of banned munitions, has accused Russia of committing war crimes in the city. The UN has since launched an investigation into crimes committed across Ukraine, and Michelle Bachelet, the UN’s human rights chief said in Mariupol “people are living in sheer terror”.

The coastal city is not just a prized target for the Russians in a geographical sense. Home to the biggest port in the Sea of Azov and one of Ukraine’s largest overall, it has long been a fierce battleground between Russian-backed separatists and the Ukrainian military.

It is also the birthplace of Azov, the far-right battalion founded by members of neo-Nazi groups that was later integrated into the Ukrainian National Guard. They played a major role in recapturing Mariupol from Kremlin-backed forces in 2014.

And so the fight against the city feels almost personal.

Complicating the worsening humanitarian crisis, there has been no mobile phone network, water, electricity, heating or gas for a month. No food or medical supplies are coming into the city.

Thousands – if not tens of thousands – of Mariupol’s once 450,000-strong population are thought to have been killed or wounded in the fighting. But no one can count the dead, let alone bury them.

An unknown number of people are believed to have also died from starvation or thirst.

The Ukrainians, meanwhile, estimate that more than 80 per cent of the city has been damaged beyond repair, or completely levelled. Recent drone footage showed an ashen moonscape that echoes other war-ravaged cities such as Aleppo in Syria.

Multiple attempts to open a humanitarian corridor into the city and establish a limited ceasefire have collapsed. In the latest effort this week, Ukraine said that several buses of aid they had tried to send in were seized by Russian forces, while the shelling continues.

And so without help to flee the city, it is up to civilians themselves to brave the onslaught and escape in their own cars or on foot through shelling, gunfire and Russian-occupied territory.

The desperate search for the missing

Overnight, the battered vehicles, bedecked with white rags, painted red crosses and signs reading “children” in Russian, roll into Zaporizhzhia.

Shellshocked refugees – who have navigated multiple frontlines to get to the volunteer-run reception – use any means possible to flee. The red crosses and signs on the cars are desperate attempts to avoid being shot or shelled en route.

One man, Nikolai, incredibly arrives on a bicycle, having cycled 200km through the war. The 32-year-old tells The Independent how he fled Mariupol last week with a friend who pushed his belongings in a pram.

He said he was detained at a checkpoint for two days by Russian-backed separatists, who suspected him because he was carrying a yoghurt drink with a brand name referencing the historic name for Western Ukraine. He says they also took issue with his blue and white striped top – as it looked like a telnyashka, the traditional undershirt worn by members of the Russian and Soviet armies.

Inside the makeshift prison where he was held, Nikolai says he met a dozen women looking for their missing husbands. He describes how the women – through the cell bars – pushed photos of their spouses, who they said had also been arrested.

“It is like they are taking revenge on the common people,” the electrician adds before getting back on his bike to cycle further west.

“There is an unknown number of people that are unaccounted for.”

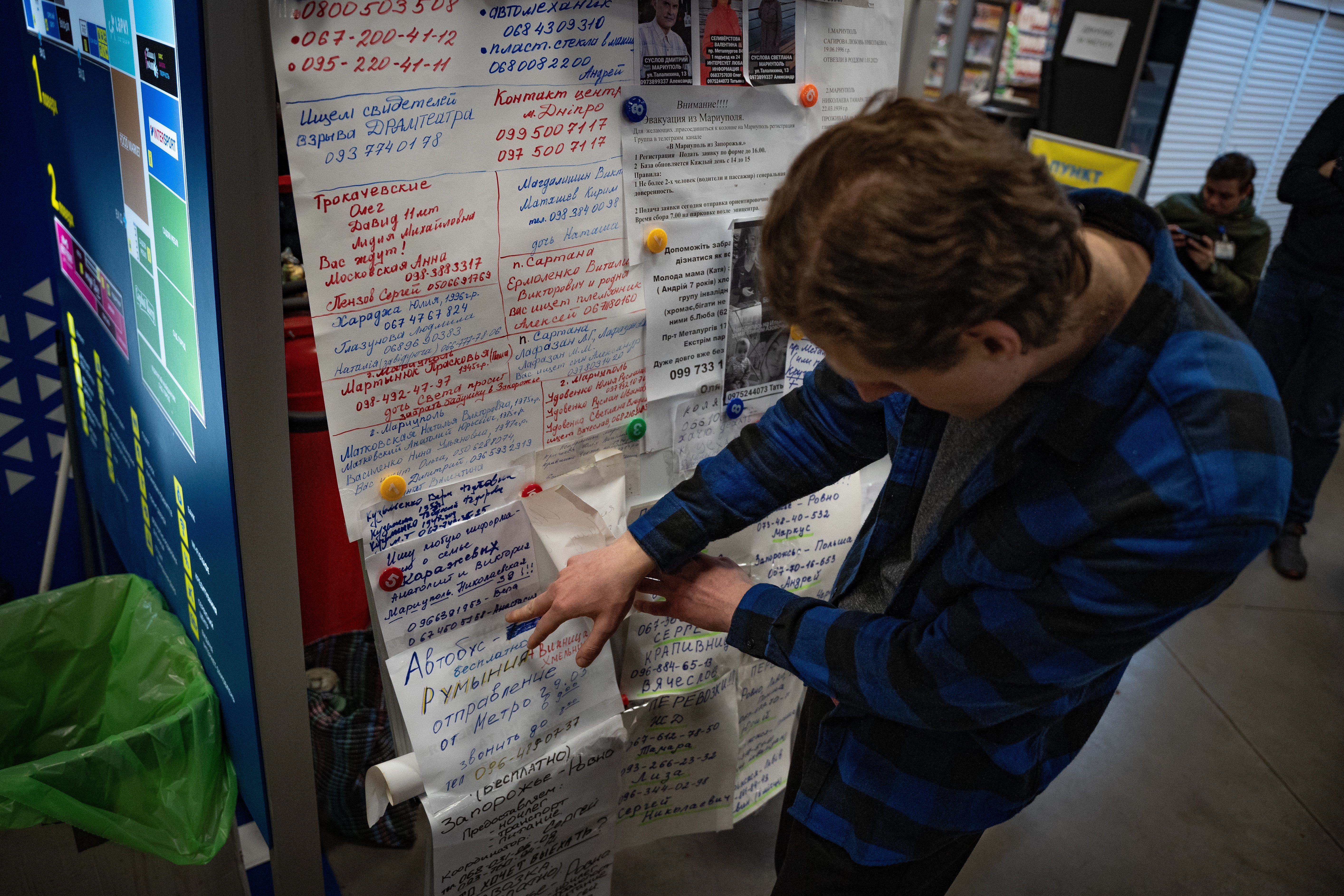

White boards erected across the reception centres of Zaporizhzhia are a chilling indicator of Mariupol’s missing.

Desperate families scribble messages and their phone numbers on scraps of paper, asking for help locating loved ones who have vanished in the nightmarish chaos and confusion. The walls of the centres are covered in photos of those unaccounted for.

“Please go to Prospect Mira Street in Mariupol and bring my relatives back. There is one adult and three children,” reads one note.

“Christine, she is a personal trainer, she last made a phone call on 2 March,” says another next, to an Instagram photo of a woman with her dog.

One message says a friend called Irina has been missing since the start of the war and was last seen in “maternity Ward 1”. “I would be grateful for any information,” reads the missive signed by a man called Stanislav.

In the background one woman, Inna, 45 considers writing her own message, as she has not heard from her husband in a month after he stayed behind in one of Mariupol’s worst-hit areas to protect their house from looters.

“The last time I spoke to him, I heard him cry for the first time in my life,” the 45-year-old says, clutching her son Ivan, 12, and their puppy Monika.

“He said he didn’t care about the apartment or possessions anymore, he just wanted to flee. He said he would try to find shelter but I don’t know if he did.”

‘It feels like vindictive revenge’

Her desperation underscores the urgent need for formal humanitarian corridors to be opened.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) attempted on Friday and over the weekend to yet again lead a convoy from Mariupol after an agreement over safe passage for civilians and a limited ceasefire had apparently been brokered with the Russians.

But Ukrainian deputy prime minister Iryna Vereshchuk said Russian soldiers blocked a convoy of 45 buses and seized 12 Ukrainian trucks containing food and medical supplies.

The ICRC later told The Independent it was unable to even deliver two truckloads of their medical supplies they had prepared to take into the city. Their convoy was also turned around.

Ultimately, the Ukrainians say they were able to evacuate a convoy of about 3,500 people who had made it out of Mariupol themselves.

This marked the single largest arrival of people from the besieged city since the war began. But again, the families interviewed by The Independent say they had to escape by their own means. Some just stumbled upon volunteers in cars looking for anyone who was alive.

“It feels like vindictive revenge – there is nothing else to explain the violence of what is happening,” says Angelica, 45, in tears as she climbed off one of the buses. “It is a genocide against the inhabitants of Mariupol.”

Behind her, a young man called Victor, compares the devastation in Mariupol to Pripyat, the long-abandoned town next to Chernobyl which was evacuated during the nuclear disaster in 1986.

“Mariupol is Ukraine’s second Pripyat but at least that town was still left intact. Mariupol has been utterly devastated.”

‘She burned alive in her bed’

In their last few days in Mariupol under fire, the adults in the shelter where Dasha’s family were hiding had stopped eating and just drank tea in order to save food for their children.

Among the 50 people who lived with them in tomb-like conditions were those who had survived the horrific bombing of the nearby local community shelter in Mariupol’s Drama Theatre on 16 March.

The survivors, who stumbled randomly into their basement one night, told the family that only 100 of the estimated 800 people taking shelter were still alive. Official estimates say at least 300 were killed.

Dasha, 21, clutching her beloved pitbull Zara, plays a video of one of the rare trips she made above ground during those weeks. It shows what appears to be Grad missiles fired at 90 degrees straight into a heavily populated civilian area, as she screams in the background.

Her father, Maksym, says he was asked on that same day to try to retrieve a disabled person trapped in a nearby flat who had not been able make it to the shelter.

As they tried to get him out, he says the Russians appeared with a missile launcher and fired.

“The trajectory was almost flat; they were directly shelling straight into neighbourhoods,” Maksym recalls with disbelief.

Their home, located in the devastated heart of the city, was repeatedly shelled, and more mobile phone videos show clawed out holes in the roof of their apartment. One missile set fire to the basement where they were hiding and nearly burned them to death.

“Everyone was screaming as we scrambled to get out, it was like the Titanic,” Dasha says, recalling the horror.

“The problem is with those who cannot run,” she adds.

In the makeshift medical centre behind them, Nadezhda, 57, who has just arrived from Mariupol and is suffering from an injury caused by shrapnel, says her aunt burned alive as no one could move her to the basement in time when the missiles struck.

“It is the elderly, the disabled, the sick, and the wounded I worry about the most,” she says in confused tears as volunteer medics tend to her leg.

“My aunt suffocated from the smoke in her bed without realising what was happening to her. Then her body burned.”

‘What about the ones we left behind?’

For Alisia, like all of those arriving at the reception centres in Zaporizhzhia, getting to safety does not mean the nightmare is over. She gathers her daughters, her mother, their kitten and a few plastic bags of belongings, to take them further west. But the scars are deep.

Her husband Roman, 40, also a bank worker, is still stuck in Russian-occupied territory as he gave up his place in the bus that took them to safety for other women and children. There is no way to communicate with him and so her only hope is that he joins a new convoy to safety.

Her brother and her niece, meanwhile, remain trapped on the outskirts of the city. The last she heard, they had run out of food and planned to try to walk more than 200km to Zaporizhzhia.

Before she left, Alisia also spent three days under fire going from shelter to shelter trying to find husband’s parents, who were living in a different neighbourhood. They too are missing.

Her home, meanwhile, is levelled, and her life destroyed.

“I guess we will try for other parts of Europe to start a new life,” she says, visibly dazed.

Behind her a fresh stream of displaced people from Mariupol arrive, blinking haunted in the strip light. They drag what little they managed to salvage of their lives behind them.

“But what about the rest of my family who didn’t make it out? The elderly living alone. Those unable to get to the shelters.”

“All I can think about is the ones we left behind.”

The Independent has a proud history of campaigning for the rights of the most vulnerable, and we first ran our Refugees Welcome campaign during the war in Syria in 2015. Now, as we renew our campaign and launch this petition in the wake of the unfolding Ukrainian crisis, we are calling on the government to go further and faster to ensure help is delivered. To find out more about our Refugees Welcome campaign, click here. To sign the petition click here. If you would like to donate then please click here for our GoFundMe page.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks