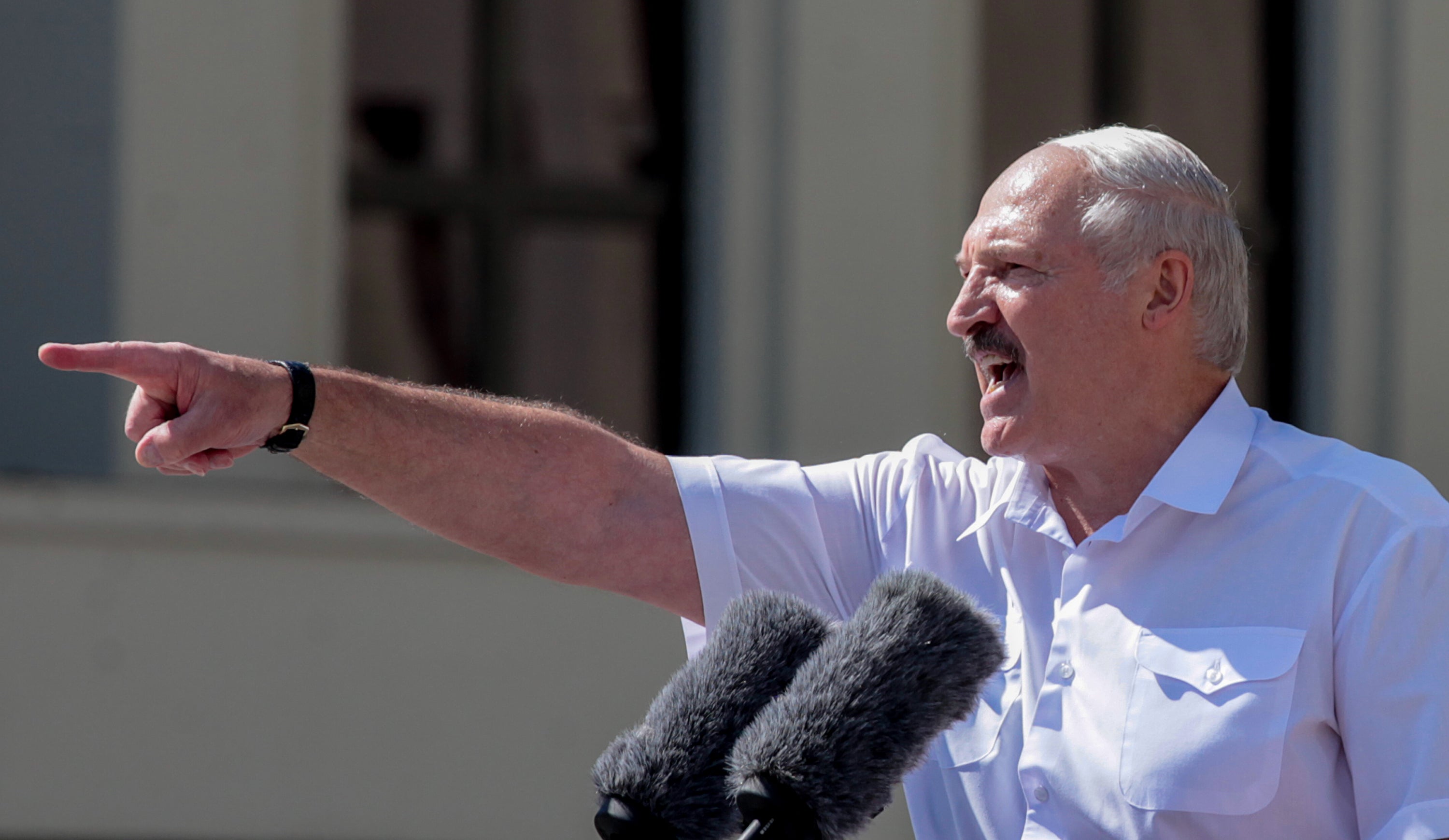

The hackers trying to overthrow Belarusian leader Lukashenko

Belarusian hackers have released portions of a huge data trove that reveals the inner workings of the most secret police and government databases to try to get rid of Lukashenko, writes Ryan Gallagher

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Opponents of the Belarus government say they have pulled off an audacious hack that has compromised dozens of police and interior ministry databases as part of a broad effort to overthrow President Alexander Lukashenko’s regime.

The Belarusian Cyber Partisans, as the hackers call themselves, have released portions of the huge trove they say includes some of the country’s most secret information. It contains lists of alleged police informants, personal information about top government officials and spies, video footage from police drones and detention centres and secret recordings of phone calls from a government wire-tapping system, according to interviews with the hackers and documents reviewed by Bloomberg News.

Among the pilfered documents are personal details about Lukashenko’s inner circle and intelligence officers. In addition, there are mortality statistics indicating that thousands more people in Belarus died from Covid-19 than the government has publicly acknowledged, the documents suggest.

In an interview and on social media, the hackers say they also sabotaged more than 240 surveillance cameras in Belarus and are preparing to shut down government computers with malicious software named X-App.

Belarus’s interior ministry didn’t respond to requests for comment. On 30 July, the head of the country’s KGB security agency, Ivan Tertel, said in a speech aired on state television that there had been “hacker attacks on personal data” and a “systematic collection of information” which he blamed on the work of “foreign special services”, according to local news website Zerkalo.io.

While the immediate impact of the hack isn’t entirely clear, experts say the long-term consequences could be significant, from undermining government proclamations to bolstering international efforts to sanction or prosecute Lukashenko and his subordinates.

“If ever Lukashenko ends up facing prosecution in the International Criminal Court, for example, these records are going to be incredibly important,” says Tanya Lokot, an associate professor at Dublin City University who specialises in protest and digital rights issues in eastern Europe.

The wire-tapped phone recordings obtained by the hackers revealed that Belarus’s interior ministry was spying on a wide range of people, including police officers

Nikolai Kvantaliani, a Belarusian digital security expert, says the data exposed by the Cyber Partisans showed, “that officials knew they were targeting innocent people and used extra force with no reason”. As a result, he says, “more people are starting to not believe in propaganda” from state media outlets, which suppressed images of police violence during anti-government demonstrations last year.

The hackers have teamed up with a group named Bypol, created by former Belarusian police officers, who defected following the disputed election of Lukashenko last year. Mass demonstrations followed the election and some, police officers were accused of torturing and beating hundreds of citizens in a brutal crackdown.

Aliaksandr Azarau, a former police lieutenant colonel who headed an organised crime and corruption unit, says he quit his job last year after witnessing election fraud and police violence. He moved to Poland and joined Bypol, which he says had been working with the Cyber Partisans since late last year. Azarau says the information the hackers released is authentic and that Bypol plans to use it to hold corrupt police and government officials accountable.

The wire-tapped phone recordings obtained by the hackers revealed that the interior ministry was spying on a wide range of people, including police as well as officials working with the prosecutor general, according to Azarau. The recordings also offer audio evidence of police commanders ordering violence against protesters, he says.

“We are cooperating closely with the Cyber Partisans. The information from them is very important for us,” Azarau says. “They hacked most of the main police database and they downloaded all information, including information from the security service wire-tapping department, the most secret department of our police.

“We found that they were wire-tapping the most famous law enforcement agents and now we can listen to them and understand their orders to commit crimes against people.”

Azarau says the group hopes to use the information to pursue sanctions against Belarusian officials in the EU and the US. Both the US and the UK have announced sanctions against individuals and entities tied to Lukashenko’s regime.

During other periods of unrest in recent years, activist hackers, known as hacktivists, have breached government computers. During the Arab Spring in 2011, hackers affiliated with the Anonymous collective carried out distributed denial of service attacks to bring down government websites in Tunisia and Egypt. Meanwhile, in Turkey, a Marxist hacker group named RedHack breached police, corporate and government databases in a series of attacks staged between 2012 and 2014. In 2016, a group of hackers calling themselves the Ukrainian Cyber Alliance formed to counter Russian aggression in Ukraine. They compromised Russian Ministry of Defence servers and breached emails of alleged Russian militants and propagandists.

Gabriella Coleman, a professor at McGill University and an expert on hacktivism, says that the Cyber Partisans’ highly organised and persistent hacks, paired with its collaboration with former police officers, set it apart from other groups, whose operations have often been chaotic and experimental. “I don’t think there are a lot of parallels to this,” says Coleman. “That they are so sophisticated and are attacking on multiple levels, it’s not something I’ve seen before except in the movies.”

A spokesman for the Cyber Partisans, who requested anonymity due to security concerns, says that the group includes about 15 people, three or four of whom focus their efforts on what he described as “ethical hacking” of Belarusian government computers. The rest work on data analysis and other tasks, he says. Most of those involved with the group are Belarusian citizens who work in the information technology business, the spokesman says, and some had worked on so-called penetration testing, a method of evaluating the security of computers and networks by simulating an attack on them.

Earlier this year, an affiliate of the group obtained physical access to a Belarus government facility and broke into the computer network while inside, the spokesman says. That laid the groundwork for the group to later gain further access, compromising some of the ministry’s most sensitive databases, he says. The stolen material includes the archive of secretly recorded phone conversations, which amounts to between a million and two million minutes of audio, according to the spokesman.

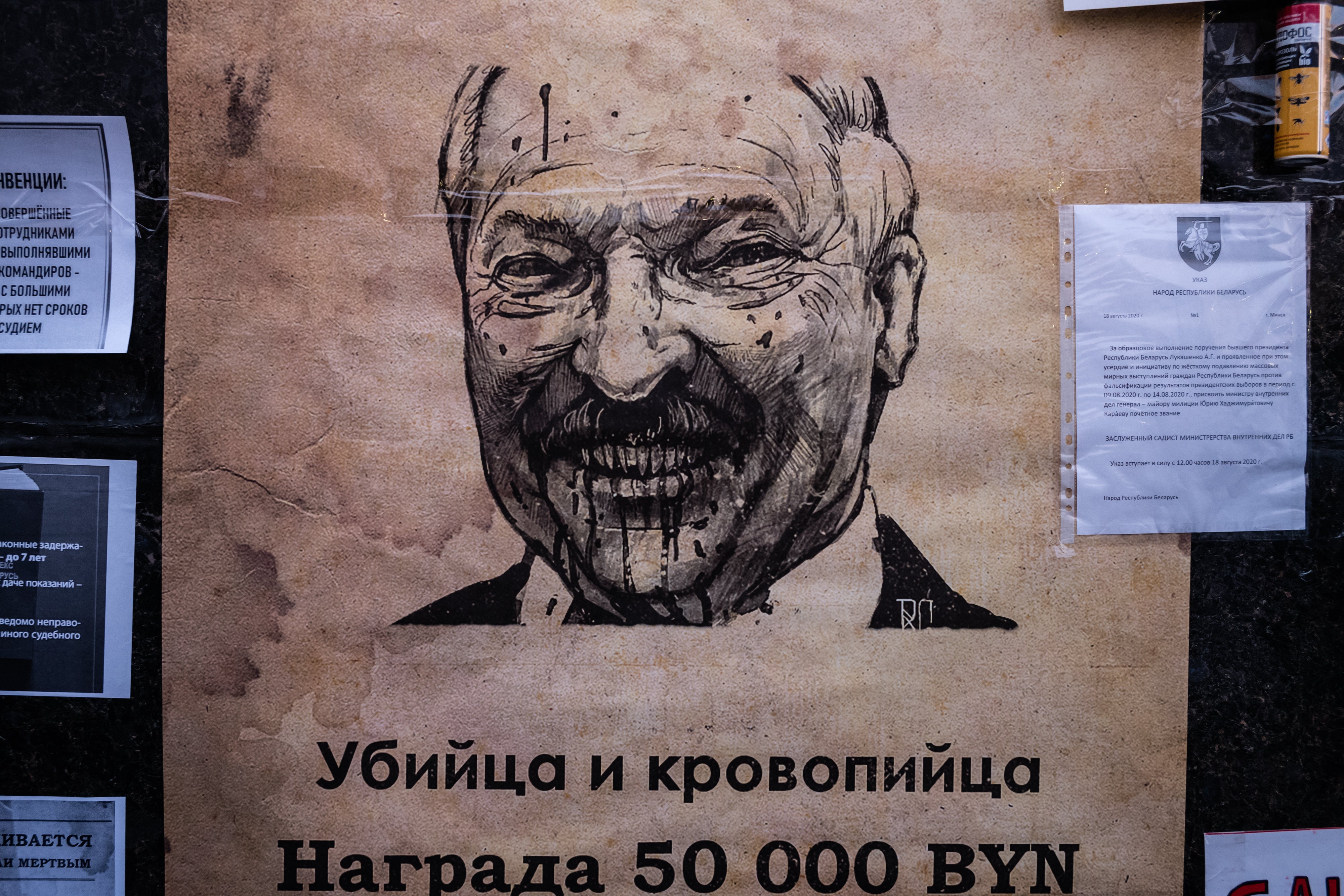

The hackers joined together in September 2020, after the disputed election. Their initial actions were small and symbolic, according to screenshots. They hacked state news websites and inserted videos showing scenes of police brutality. They compromised a police “most wanted” list, adding the names of Lukashenko and his former interior minister, Yury Karayeu, to the list.

And they defaced government websites with the red and white national flags favoured by protesters over the official Belarusian red and green flag.

Those initial breaches attracted other hackers to the Cyber Partisans’ cause and as it has grown the group has become bolder with the scope of its intrusions. The spokesman says its aims are to protect the sovereignty and independence of Belarus and ultimately to remove Lukashenko from power.

Franak Viacorka, a senior adviser to exiled opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, says the hackers were engaged in “non-violent resistance”.

“When people face terror and repression, they can’t defend themselves with arms. They can defend themselves with creativity,” Viacorka says.

Names and addresses of government officials and alleged informants obtained by the hackers have been shared with Belarusian websites, including Blackmap.org, that seek to “name and shame” people cooperating with the regime and its efforts to suppress peaceful protests, according to Viacorka and the websites themselves. That has created difficulties for officials working for the Lukashenko regime, Viacorka says.

“It creates pressure on them. It creates fractures within the government and a feeling that you can’t trust anyone when you are in the system.”

The Cyber Partisans say they are working with other groups to continue to hack government infrastructure. They are progressing toward what they call Moment X, a period that will combine computer sabotage with physical uprising on the streets, resulting in what the group hopes will be the overthrow of the Lukashenko government.

Azarau, the former police lieutenant colonel, is pursing the same goal, working with Bypol to create an “undercover Belarusian army,” he says. “We are building structures inside, and one day we will be ready to change the power, the regime.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments