As MH370 conspiracy theories continue to swirl, why has compelling new evidence not revived the search?

Three years after the Malaysia Airlines jet vanished, new scientific analysis suggests that the most expensive search in aviation history devoted vast amounts of time and money to looking in the wrong place

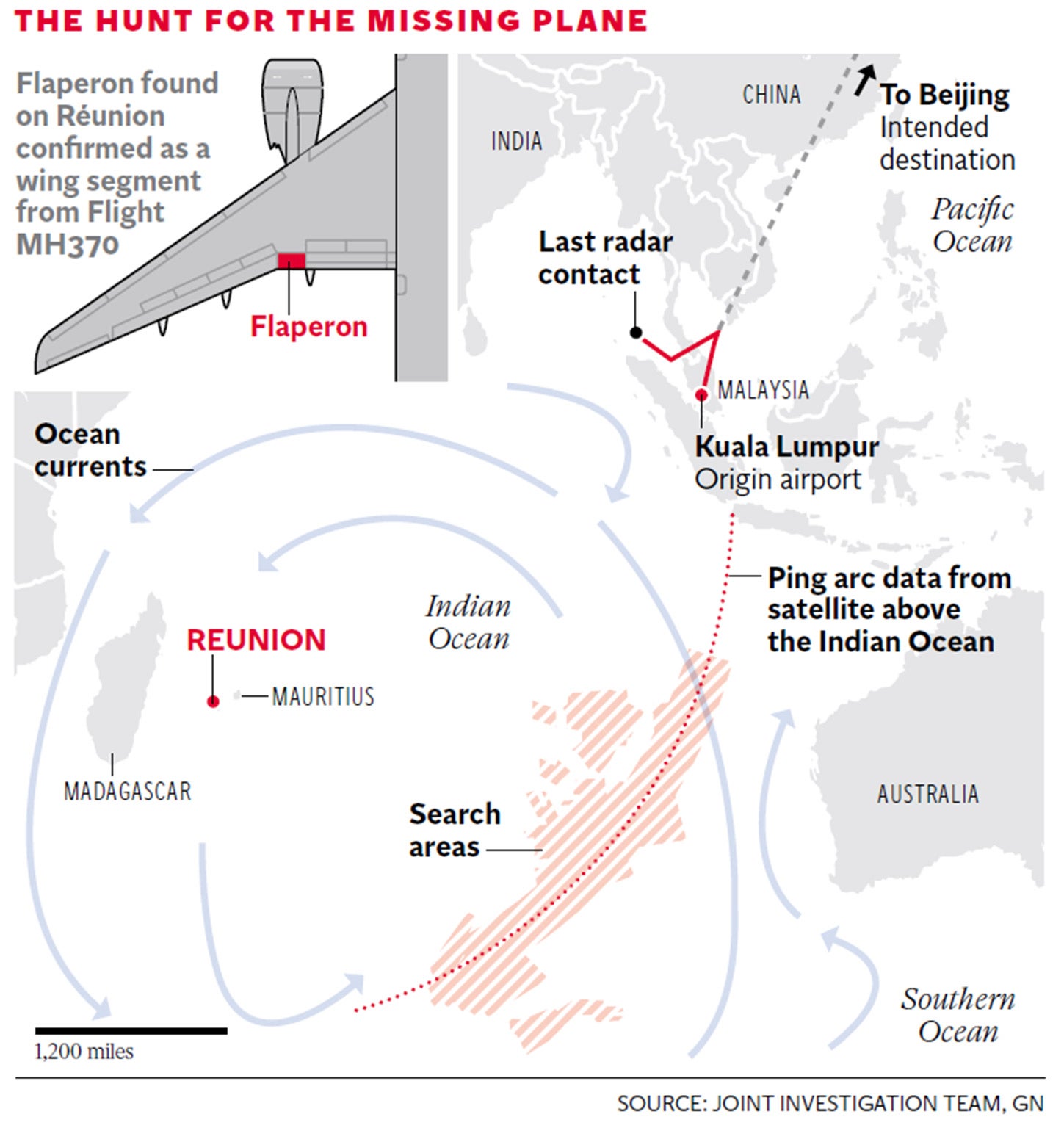

At 00:41 on 8 March 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 took off from runway 32R at Kuala Lumpur International Airport, bound for Beijing with 227 passengers and 12 crew.

At 01:19 someone in the cockpit bade farewell to Malaysian air traffic control with the words: “Good night, Malaysian three seven zero.”

Those were the last words ever heard from flight MH370.

The last radar contact was at 02:22, the final automatic “partial handshake” with a satellite above the Indian Ocean was at 08:19.

And then MH370, with 239 people on board, seemingly vanished into thin air.

As the conspiracy theories swirled – ranging from a secret landing on the US airbase of Diego Garcia, to the world’s first remote-controlled “cyberhijack” – the search for MH370, costing $160m (£125m), became the most expensive in aviation history.

At one point those seeking the final resting place of the missing Boeing 777 faced having to scour about 1.5 per cent of the Earth’s surface, nearly three million square miles, in two arcs stretching from northern Thailand to Kazakhstan, and from Indonesia into the southern Indian Ocean.

They soon “narrowed it down” to a vast, remote area of the southern Indian Ocean, braving the effects of tropical cyclones and some of the roughest waters on the planet to use drones and sonar equipment to scour an area of seabed that was less well-known than the surface of the moon.

They found new underwater volcanoes, anchors, long-lost wrecked ships, but no sign of the bulk of MH370.

Then in January this year, after searching 120,000 square km (46,300 square miles) of ocean, the Malaysian, Australian and Chinese authorities announced that their search was being “suspended”.

Despite every effort,” said the communique from the Joint Agency Coordination Centre (JACC), “using the best science available, cutting edge technology, as well as modelling and advice from highly skilled professionals who are the best in their field, unfortunately, the search has not been able to locate the aircraft.”

And so three years on, for the relatives, the anguish of not knowing what happened to the 239 remains as raw as ever. Because there can be no doubt that the ending of the search has done nothing at all to close down speculation about the fate of MH370 and those who flew in it.

Indeed it seems the plot has now thickened further. Research commissioned by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau has now suggested that for a large part of the search for MH370, everyone was looking in the wrong place.

Since November 2015 the search had prioritised an area between the latitudes 36°S and 39.3°S. But the new research suggests the wreck of the bulk of the plane is further north, in a region near 35°S.

Scientists from Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) based their findings on the first piece of MH370 debris to be found: a flaperon, an aircraft wing part functioning as both flaps and ailerons, that drifted across the ocean until it was found by a council worker having his lunch break in July 2015 on a beach on the island of Réunion, east of Madagascar.

The scientists acquired a genuine Boeing 777 flaperon, cut it down to match photographs of the MH370 flaperon found on the beach, and then analysed how it drifted over water.

The resulting drift patterns and the fact that so far MH370 debris has been found on Réunion, Madagascan and African shores but not on Australian beaches led them to conclude: “The region near 35°S is the only one that is consistent. The available evidence suggests that all other regions are unlikely.”

The publication of this report has added further weight to the argument advanced by the anguished relatives since January: that the search had ended too soon, that if a new 25,000km² (9,650mi²) area could be examined, the mystery of MH370 could finally be solved.

And it is correct to talk about adding further weight: because the CSIRO scientists stressed that their report merely added a greater degree of certainty to their earlier drift analysis, the one they conducted last year using a replica flaperon.

This earlier drift analysis had informed a “First Principles Review” of the MH370 search, conducted under the auspices of the Australian Transport Bureau.

As a result, in December 2016 – one month before the search was called off – the First Principles Review had recommended examining a new, more northerly area – the 25,000km² patch of ocean subsequently cited by the relatives.

And yet the January JACC communique announcing the suspension of the search appeared to brush this aside by stating: “Whilst combined scientific studies have continued to refine areas of probability, to date no new information has been discovered to determine the specific location of the aircraft.”

If the new CSIRO report were not enough to prompt renewed controversy, as so often happens with the mystery of MH370, an alternative narrative has also swiftly emerged.

Last Sunday a loose affiliation of interested scientists calling themselves the Independent Group revealed drift analysis of their own, conducted by Richard Godfrey, suggesting that the wreck of MH370 might lie around latitude 30°S, much further north than even the new 35°S area.

“The pre-conceived idea, that ‘other evidence’ constrains the MH370 End Point to between 32°S and 36°S is a false assumption,” insisted Godfrey, a Frankfurt-based aerospace engineer.

He wondered, for example, about the CSIRO factoring into its calculations the absence of MH370 debris in Australia.

Wasn’t it possible, he suggested, that something could have washed up unnoticed somewhere along the 20,781 km (12,913 miles) of the relatively sparsely populated coast of western Australia, where 86 per cent of the population lives within the cities of Perth, Bunbury, Busselton and Mandurah?

Godfrey also suggested that much of the area around 35°S had in fact been searched prior to November 2015 – despite the CSIRO report having sought to explain that “the new search area, near 35°S, comprises thin strips either side of the previously-searched strip”.

In his report summary, Godfrey seemed to go as far as flatly contradicting this CSIRO explanation by asserting that: “An MH370 End Point at 35°S does not fit the fact that the underwater search has already discounted this location to a 97 per cent level of certainty.”

Amid such technicalities remain the relatives of the 239, and the stark question posed by KS Narendran, a human resources consultant from Chennai, India, who has lost Chandrika Sharma, his wife of 25 years.

“How,” he wrote last month, “can a large jetliner claiming to be the safest, most sophisticated and successful commercial aircraft, with hundreds of passengers on board, just disappear?”

Partly, some think, the answer lies with the chaos that attended the first days of the search for MH370.

The initial efforts sent the bulk of 40 search aircraft and 24 boats in completely the wrong direction – to the east, to look in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea between Malaysia and Vietnam.

At first MH370 was not recognised as the unidentified aircraft last picked up at 02:22 by a military radar which placed it 370km (230 miles) from Penang Island on Malaysia’s western coast, far to the west of where everyone was looking.

Only on 10 March, two days after the disappearance, did the Malaysian Air Force admit that MH370 seemed to have made an unexpected sharp “turn back” to the west, deviating from what should have been its easterly course towards Beijing.

Adding to the confusion was that the Malaysian authorities reportedly initially denied what analysis of the satellite handshakes was now revealing: that for hours after disappearing from the military radar screen, MH370 had kept on flying.

Only on 15 March, seven days after the disappearance, did Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak announce publicly that the South China Sea search would be stopped.

The scenario outlined by the Malaysian PM was now of a jet that had flown on for at least seven hours after the last 01:19 voice message from the cockpit.

The satellite data, he said, suggested the need to look along two possible arcs encompassing a total of nearly three million square miles: the northern one stretching from Thailand to Kazakhstan, the southern from Indonesia into the Indian Ocean.

Further analysis soon allowed the focus to turn exclusively to the southern Indian Ocean.

But by then about 100 relatives waiting for news in Beijing had delivered a handwritten ultimatum demanding proper clarity after so many contradictions.

“We don’t believe Malaysia Airlines any more,” their spokesman told a crowd of reporters. “Sorry everyone, we just don’t believe them.”

China, its nationals making up two-thirds of the passenger manifest, weighed in with statements stretching the bounds of diplomatic politeness.

The Malaysian prime minister’s 15 March disclosures had been “painfully belated”, said Xinhua, China’s state news agency. “Due to the absence of timely authoritative information, massive efforts have been squandered and numerous rumours have been spawned, repeatedly racking the nerves of the awaiting families.”

It was undeniable that the gap left by an absence of consistent official information was being filled by a whole host of theories, some credible, some completely untethered from reality.

Traumatised relatives found themselves accused online of having faked their relationships with the vanished passengers, as part of some sort of “arch-Zionist” Mossad disinformation plot to spread fear of Islamist terrorism. In one version, they became a “clique of falsifiers” faking relationships with “phony passengers” on a flight that itself had never even existed.

Back in the real world, Najib’s press conference claim that someone had deliberately switched off MH370’s communications reporting system before turning it west re-ignited the hijacking theories.

These had initially focused on two Iranian men named as Pouria Nour Mohammad Mehrdad, 18, and Delavar Seyed Mohammadreza, 29, who had been travelling on stolen passports.

But neither man was found to have had any links with terrorist groups and they were largely written off as asylum seekers travelling – as is relatively common – with false documents.

Instead the speculation turned to other passengers, and the crew – especially the crew.

Malaysian police were searching the homes of Captain Zaharie Ahmad Shah and 27-year-old co-pilot Fariq Abdul Hamid.

Captain Shah in particular became the focus of enduring speculation. Perhaps the 53-year-old Muslim wasn’t really the mild-mannered grandfather who raised money for the poor and enjoyed watching recordings of the renowned atheist Richard Dawkins?

Wasn’t he, after all, a supporter of the opposition Malaysian People’s Justice Party?

And most intriguingly of all, what to make of the six-screen flight simulator that he had built in his own home?

Was this really just another “aviation junkie” seeking to share an innocent passion, as suggested by such Facebook posts as: “Time to take to the next level of simulation motion! Looking for buddies to share this passion”?

Over time, speculation about Captain Shah has only intensified. Last July it was reported that an FBI forensic examination of his flight simulator’s hard drive had revealed he had plotted one practice route – among thousands, it should be said – that took an aeroplane into the southern Indian Ocean.

Comparisons started to be drawn between Captain Shah and Andreas Lubitz, the suicidal co-pilot of Germanwings Flight 9525, who in March 2015 had locked the cockpit door and deliberately flown the plane into a French mountainside.

There were unconfirmed reports of a marriage breakdown, speculation about a life insurance scam. Was MH370 another case of pilot suicide-murder?

“Someone was looking at Penang,” experienced Boeing 777 captain Simon Hardy told the BBC in April 2015, after analysing MH370’s last known movements. “Someone was taking a long, emotional look at Penang.

“The captain was from the island of Penang.”

“It flew in and out of the countries [Malaysia and Thailand] eight times,” added Mr Hardy. “This is probably very accurate flying rather than just a coincidence. Both air traffic controllers in both those countries would probably assume that the aircraft was in the other country’s jurisdiction and not pay it any attention.”

Some have sought to match the pilot-suicide theory with investigators’ suggestions that MH370 became a “ghost plane” flying for hours without human control, probably on autopilot, with crew and passengers rendered unconscious or dead by oxygen starvation.

Had a suicidal Captain Shah deliberately depressurised the jet, leaving everyone with just 20 minutes more oxygen, to be breathed from the masks that would have automatically dropped down from above their seats, before unconsciousness rendered them oblivious to their impending deaths?

Other theories have suggested “the world’s first cyber-hijack” using a mobile phone or even a USB stick to hack into the plane’s control software.

Or perhaps Captain Shah was a non-suicidal hero who steered a stricken jet away from heavily populated areas to carry out a controlled ditching in a remote stretch of ocean?

A controlled ditching was, at least, effectively ruled out by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau last November. It reported that examination of wing flap debris that had by now drifted ashore, combined with “burst frequency offset” analysis of the final 08:19 satellite handshake, suggested “a high and increasing rate of descent” of up to 25,000 feet per minute – a death spiral as some commentators have described it.

There are other theories, ranging all the way up to alien abduction, and plenty of seekers. One man, Blaine Gibson, from Carmel, California, having already travelled to Ethiopia in search of the Lost Ark of the Covenant, has devoted much of the past three years to scouring foreign beaches for MH370 debris.

Such independent investigators may soon be joined by others, with more deeply personal motives.

Despairing of the suspension of the official search, relatives of the MH370 passengers last month revealed they would be seeking to raise $15m (£12m) to fund their own hunt for the missing plane.

“We do not envisage such a search replacing the government or in any way releasing the governments involved in the search thus far from their obligations,” wrote Mr Narendran, explaining that the relatives were acting out of “a sense of anger, betrayal and chaos”.

If the official search did not resume, he said, “We will work to elicit fund commitments from world governments, corporations, high net-worth individuals and the travelling public.”

“This is not likely to be easy,” he admitted.

But what choice did he and the other relatives have?

“Like most family members of passengers,” wrote Mr Narendran, “I have survived. It is not to say that the living process has been repaired and normal has been restored.

“While I presume that lives of passengers have ended, memories are strong, vivid and make the process of looking ahead painfully difficult.

“It is made worse by the knowledge that we actually don’t know very much more than what we gathered on 8 March 2014... that a plane had just disappeared.”

And while the mystery of MH370 was unsolved, he suggested, there remained a pressing issue, not just for the relatives but for anyone travelling on a modern passenger jet: “I don’t believe we can feel safe while flying when the possibility of another similar incident lurks.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks