The extraordinary hidden life of one of Queen Elizabeth’s closest friends according to her diaries

As one of Queen Elizabeth’s longest-standing companions, Lady Pamela Hicks had encounters with Gandhi, Martin Luther King and Haile Selassie. Here, her daughter India tells Anna Tyzak about the stories she is still unearthing in her mother’s most private papers

The day after India Hicks was bridesmaid at the marriage of her godfather, King Charles, to Lady Diana Spencer, her mother sent her straight back to boarding school. Lady Pamela Hicks had been a royal bridesmaid herself, at the wedding of Prince Philip to her cousin Princess Elizabeth in 1947 and did not want the pomp and ceremony going to her 13-year-old daughter’s head.

“There was no more mention of it; she didn’t want me to think I was any more special than anyone else,” says India, a designer and humanitarian. “When we joined in royal occasions my mother always made it feel absolutely normal.”

For Lady Pamela, though, whose great-great-grandmother was Queen Victoria and who came of age in India, where her father, Lord Mountbatten, was the last viceroy, there was no normal, only fairy tales.

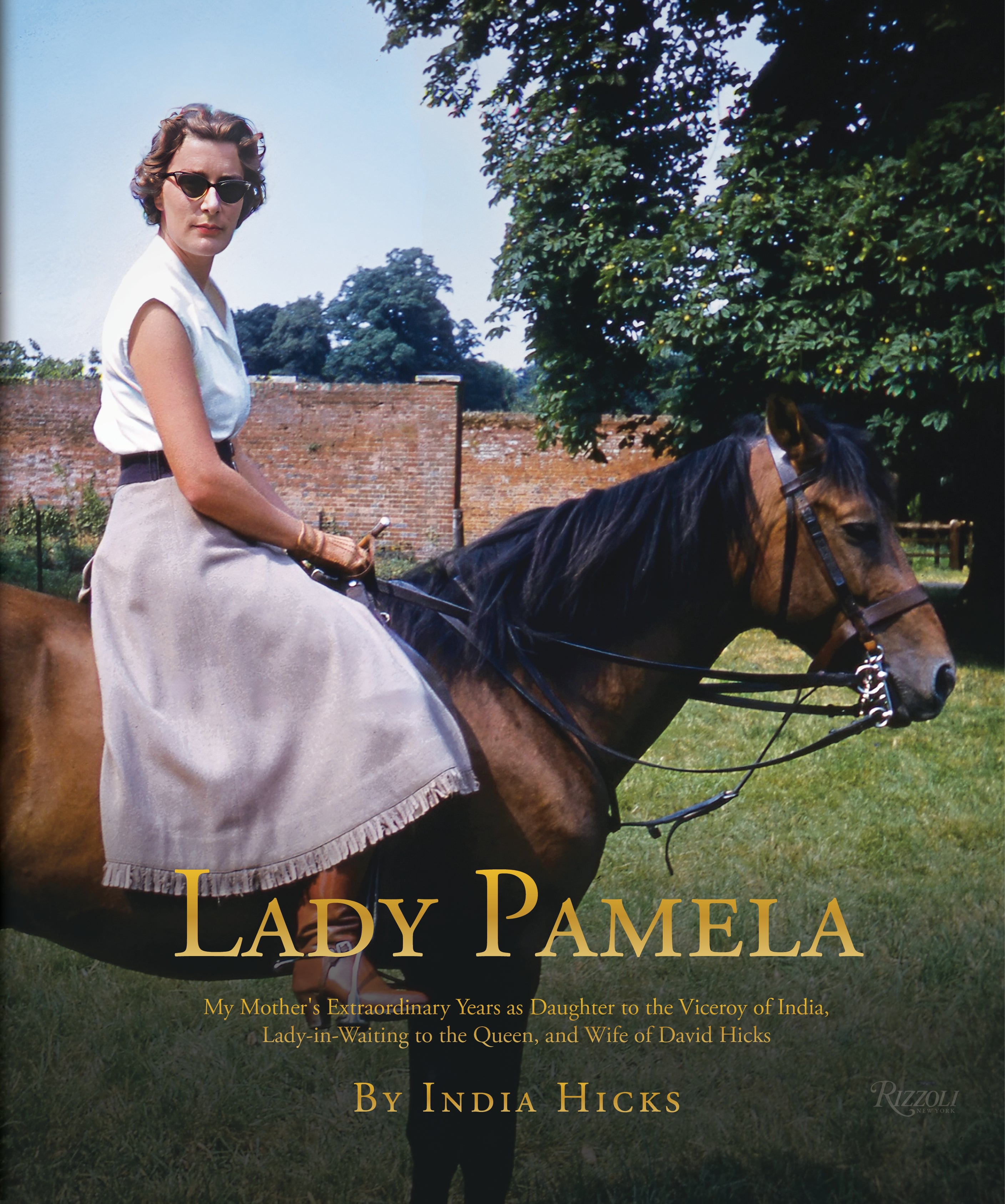

India’s new coffee table biography of her mother’s life, Lady Pamela, is a front-row look at 20th-century society, illustrated with diary extracts, photographs and mementos.

Much of it centres around the stories India herself grew up on: her mother’s encounters with Gandhi, Martin Luther King, and Haile Selassie, whose pet black panthers reminded her of Sabi, the lion she grew up with. Wild animals are a theme: her mother also had a honey bear, Rastus, who her grandmother used to discipline with a parasol, and was nearly eaten alive in the Kenyan bush as a lady in waiting to Princess Elizabeth on the first Commonwealth Tour.

The following day, when she learnt that King George VI had died in his sleep, she went to embrace her cousin before remembering herself and dropping into a curtsey. “Mum is a brilliant raconteur – she’s the voice of a fading world,” India says. “Whether that world is right or wrong it existed; it’s part of history.”

When she told her mother, who is 96 years old with a voice like Maggie Smith as the Dowager Countess in Downton Abbey, that she wanted to write her biography, Lady Pamela was baffled. She didn’t think anybody would be interested. In her mind, it was her late husband, the flamboyant designer David Hicks, who was the famous one.

On a podcast series she recorded with India in 2020, she discusses her experience of being a bridesmaid at Princess Elizabeth’s wedding as if it were any chaotic family gathering – skimming over details of her white Norman Hartnell bridesmaids dress and sapphire powder compact gifted by the groom (“it’s still in the safe”), to focus on frustrations such as a broken tiara and the Princess’s missing bouquet, which a footman has helpfully placed in a vase behind a door.

She refers to the biography as “a persuasive assault” and permitted it only on the grounds that it included a glamorous photograph of her winning the ladies’ race in Malta in a pith helmet and shades – her proudest moment – and that it began in 1928, the year she was born. “It was important to her that people realise it’s a glimpse into a bygone world,” India says.

What struck India, though, during long conversations with Lady Pamela, eating their way through boxes of violet creams, was how modern she was. Despite being born into such privilege, she was always self-aware, constantly questioning her role in life and what she could do with it.

She was also enviably resilient, probably because she moved from pillar to post during childhood, once being left by her mother and Bunny, her lover, in a castle in Hungary for six months with nannies after her mother lost the address. “These days you’d get therapy for that but my mother just got on with it. She thinks my generation is far too indulgent and emotional,” India says.

At 17, the same age as India’s own daughter, Domino, her mother was working in a medical centre in Delhi, helping treat smallpox and TB; her patients were Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and Buddhists. When Princess Elizabeth, who was three years older, asked her to be her lady in waiting, she saw it as her honour and duty; chatty letters from the Princess suggest that she considered Pamela a friend and confidante.

“My mother was reliable, discreet, and shared the same sense of humour. Later, when the Queen was busy or she’d just had a baby she’d say, “Pammy darling, would you think about coming back?”

India has always been close to her godfather, the King, and Queen Camilla but as an adult, she resisted moving in Royal circles. “I didn’t want to marry and live a conventional life. I wanted to make my own money and get out of the shadow of my family. My father, my grandparents, my brother, everyone was brilliant and clever and design-oriented. I wanted to stand on my own two feet,” she says.

She modelled for Ralph Lauren in her twenties before falling in love with hotelier, David Flint Wood, who was running a hotel on a small Bahamian island. India never left; her four children and one adopted son, Wesley, have been raised on the island.

Recently, she’s become more conventional, though, marrying Flint Wood in 2021 after 27 years together in a traditional ceremony in Oxfordshire with Domino as bridesmaid. Alongside her design work, she is now a patron for The Prince’s Trust and on the board of Global Empowerment Mission and Gem Mission Ukraine. “I do feel I need to earn my place in the world, which I think comes from my mother,” she says.

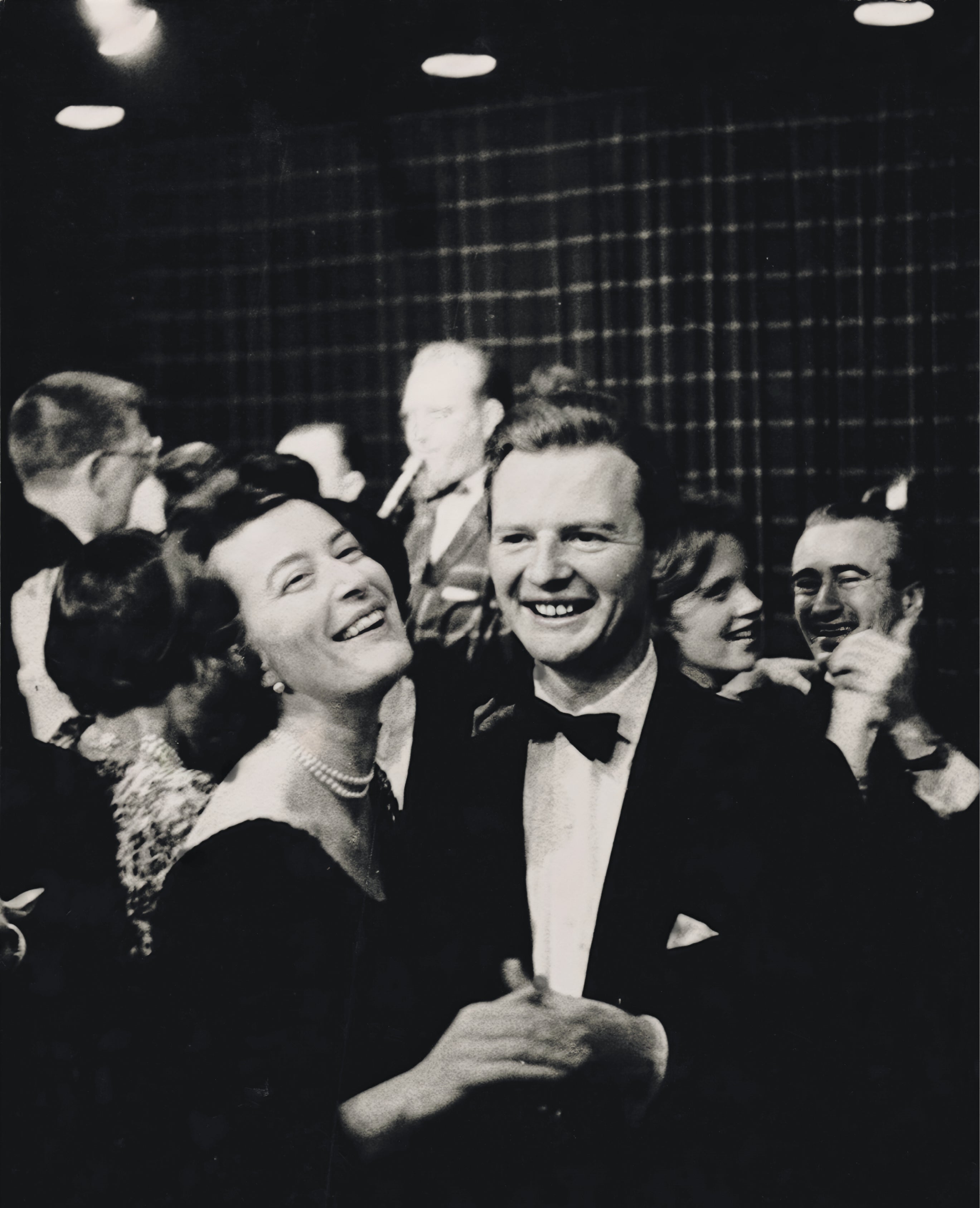

Lady Pamela also had an urge to escape convention, India suspects – although it wasn’t as easy back then. Her marriage to David Hicks, the son of an Essex stockbroker, was a rebellion against the sensible marriages her friends were making.

“She’s been through so much in India and was struggling to find her place back in Britain. My father was dazzlingly good-looking with an extraordinary mind and a whole different set of friends,” India says. “It felt refreshing – we lived in extraordinary homes with vibrant colours and a black swimming pool and were driven to school in a custom colour chocolate Jaguar.”

The flip side of this was that David Hicks was “definitely a difficult father” and “an exhausting and complicated husband” who lived much of the time in Mayfair, where he swished around in a cape and bespoke red-heeled dancing shoes.

India’s brother, Ashleigh, describes him as “the greatest snob who ever lived”. India’s relationship with her father was tricky – she’d never have gone to him with a problem – but she now feels proud to have his design genes. “I look back and appreciate that a lot of who I am is because of who he was,” she says. She’s also certain that her parents loved each other, even though they lived separate lives. “It was an extraordinary partnership – it suited my mother to be in the country with her children and animals.”

Not that Lady Pamela did much parenting. India and her siblings were brought up by nannies and then India went to Gordonstoun where she received a “fairly limited” education. When she became a parent herself for the first time she left her baby with her mother, only to find him screaming in the nursery when she returned – Lady Pamela had mistaken the wailing sound for a partridge.

They’re very close, though, she says: cut from the same cloth and find the same things funny, and she’s a devoted grandmother. “She was a parent of her time but I think she’s right in thinking that the pendulum has now swung too far the other way – I’m probably guilty of over-parenting,” India says.

Given how guarded Lady Pamela is when it comes to her personal life, India knew that what didn’t make it into the diaries would be as interesting as what did. The only reference she can find to her mother’s breast cancer in the early Eighties, for example, is in a brief postcard to her brother. “The corresponding diary entry simply says that she was driven to the hospital by the gardener – she didn’t want to be an inconvenience or create drama.”

India says, “When I asked her about it she said that breast cancer was a forbidden topic in the early Eighties. It wasn’t a conversation women were having. I dread to think how frightening it must have been: the brutal operation, the medication, the following up, she wrote nothing about it.”

Her mother is similarly tight-lipped in her diaries about the assassination of her father Lord Mountbatten by the IRA in 1979 but India knew she must include it in the book. She was 11 at the time and on holiday in Sligo with her parents, grandparents, aunt and uncle and seven cousins. She heard the bomb going off from the television room at Classiebawn Castle, where the family was staying. Her grandfather was killed as well as her cousin, Nicholas Knatchbull, 14, Nicholas’s grandmother, Doreen Knatchbull, and Paul Maxwell, a crew member.

“In that chapter, I only really scratch the surface of several tragedies that came into my mother’s life at the time – it’s meant to be a coffee table book – but I wanted people to recognise that she suffered, too, and the example my mother and aunt set about grief and understanding and moving forward was quite remarkable. They never lived a life of bitterness and I think there are lessons to be learnt from their behaviour.”

Does she think that the current Royal Family has the grit to survive the modern era? The younger royals are, in her view, getting it right, although it must be very difficult right now, she says.

She admits she feared for her godfather, King Charles, coming to the throne after his mother’s flawless reign. “There could have been a slight awkwardness in him coming on board and yet he hasn’t put a foot wrong and the English public has embraced him,” she says. “It’s a very different reign but he has a very strong wife beside him.”

She particularly approves of Queen Camilla elevating the role of lady in waiting. “She has a remarkable circle of ladies in waiting but calls them companions, which is perfect. It sums up so much of what that role is,” India says.

For Lady Pamela, the Queen’s death in 2022 was the closing of a chapter. She wore black for a month as she mourned her monarch, cousin and close friend. India accompanied her to the funeral at Westminster Abbey and the committal service at St George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle, which she says was one of the most moving experiences of her life.

“I was there as my mother’s walking stick,” she says. “As the coffin approached, she whispered to me to get her out of her wheelchair. Her 93-year-old knees were creaking and sore but she went down into a deep curtsy and stayed there until the coffin had moved very slowly past. Only then did she stand up.”

Lady Pamela: My Mother's Extraordinary Years as Daughter to the Viceroy of India, Lady-in-Waiting to the Queen, and Wife of David Hicks (£46, Rizzoli International Publications) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments