I’ve spent years trying to unravel boarding school damage - Charles Spencer and Nicky Campbell are not alone

Both Charles Spencer and BBC presenter Nicky Campbell have recently talked about the sadistic cruelty they experienced as children at their independent schools. As a teacher from the Edinburgh Academy is convicted of “cruel and unnatural acts”, psychotherapist Joy Schaverien reflects on the devastating consequences for pupils who can suffer from ‘boarding school syndrome’ all their adult lives

It is well known that British boarding schools are favoured by the aristocracy and deemed to confer social advantage on their alumni. It is also widely acknowledged that some have historically fostered a tradition of brutality and emotional deprivation among their pupils, with long-lasting effects.

One only needs to look at the beatings, humiliation and loss of self-worth suffered by the victims of Edinburgh Academy teacher John Brownlee that emerged this week to see how harrowing and life-changing an experience it can be.

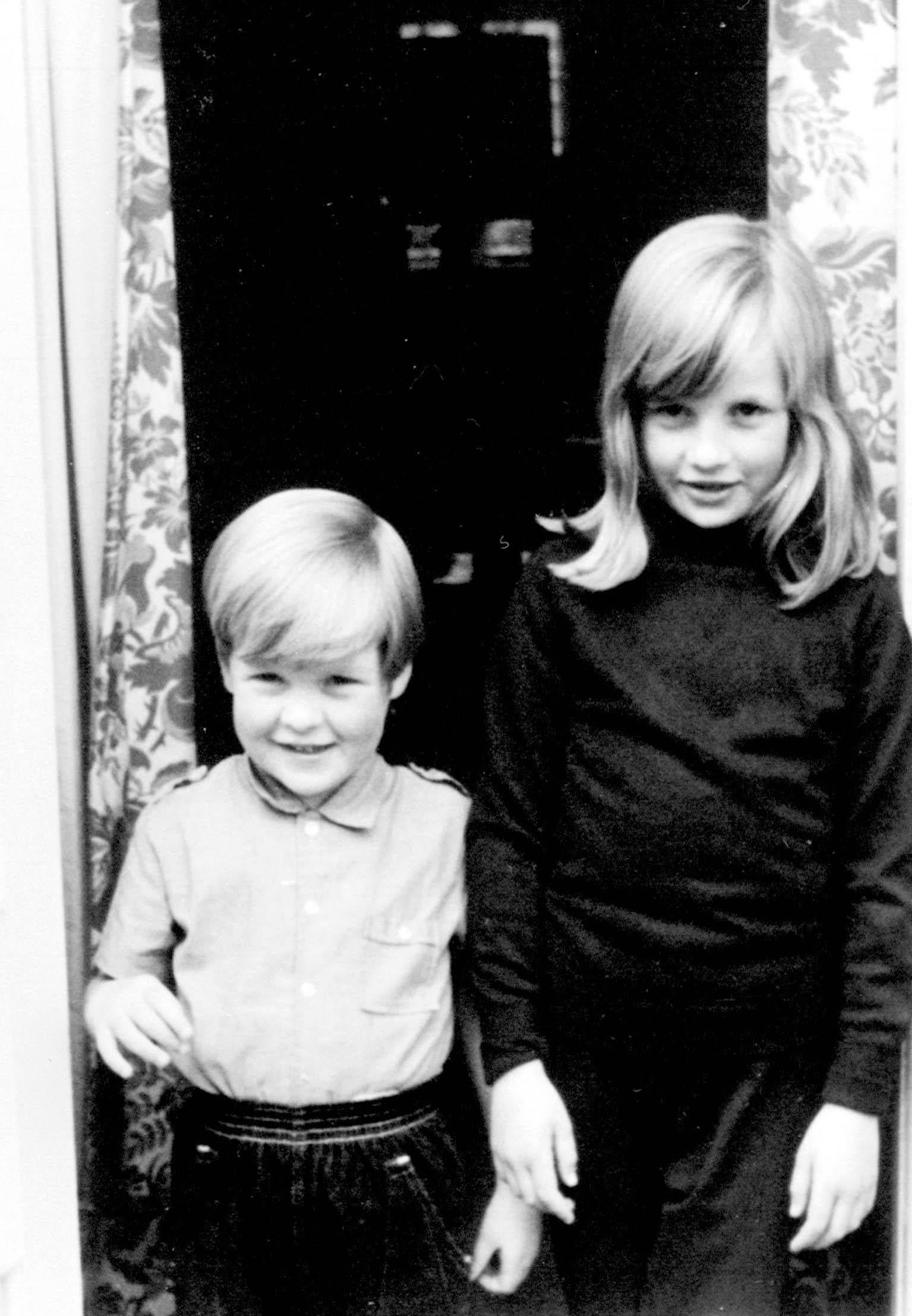

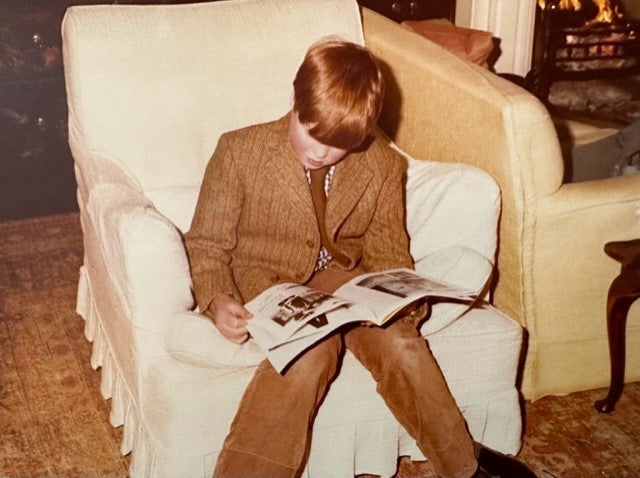

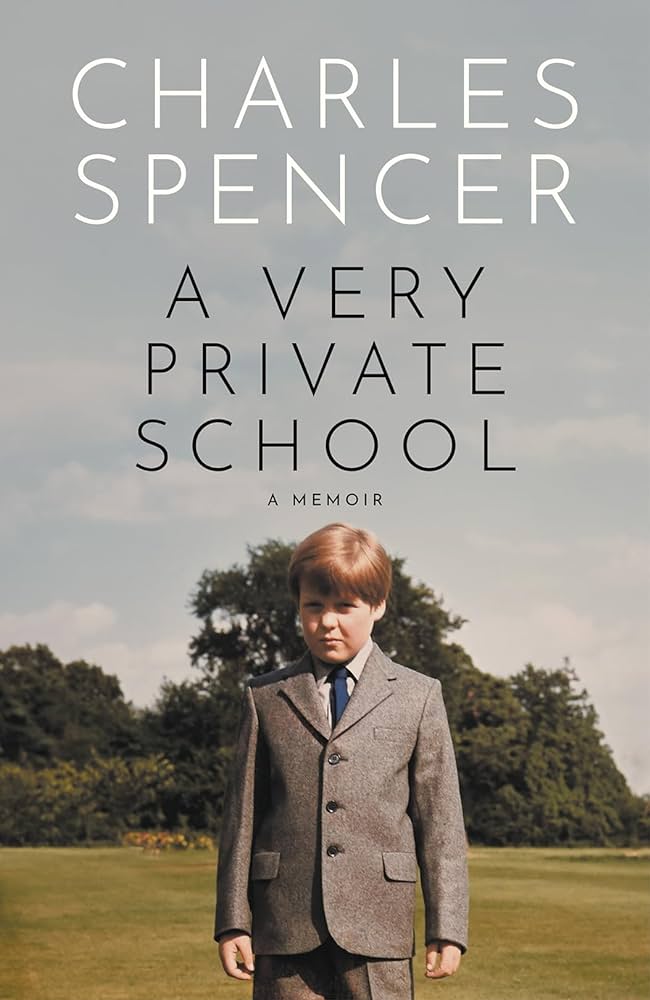

With the recent publication of Charles Spencer’s courageous memoir A Very Private School, came renewed debate around the neglect and privations that have haunted generations of children who were abandoned at the age of seven or eight to a childhood of institutional care. A conversation that is likely to intensify following this week’s court ruling that an ex-teacher Brownlee inflicted “cruel and unnatural acts” on pupils at Edinburgh Academy. A decision welcomed by former pupil, BBC presenter Nicky Campbell, who has spent years campaigning for accountability about abuse at the private school.

Unlike those who are taken into the care of the local authority, however, children in boarding schools are considered to be privileged.

Forms of punishment that had become unacceptable in other echelons of society were condoned in British boarding schools until the late 1990s, and the tradition of sending children away at such a young age endures among parents with social aspirations for their children, as well as those for whom such an education is funded by the military and diplomatic service.

However, as Spencer illustrates, being sent away to a cruel and often abusive environment at such a young age can inflict untold damage that lasts a lifetime.

As a psychotherapist, I know only too well the lasting harm of these childhood traumas and how deeply they can be buried. In my book Boarding School Syndrome: The Psychological Trauma of the Privileged Child, now considered a seminal text in this field, my research addressed the consequences of the losses and abuses suffered by boarders.

I discovered that the oft-repeated and well-known mantra “It never did me any harm” can be a face-saving myth favoured by those who are ashamed to admit what has happened to them.

I have met and heard the stories of adult men and women suffering from depression because of it. In mid-life, and often with successful careers, many came to me struggling with intimate relationships, and their hidden stories tumbled out.

A pattern of symptoms and common behaviours emerged, and I named it “boarding school syndrome”. With their permission, I told their stories – and identified that their problems as adults were a result of multiple childhood traumas, with their experiences of school at the root.

Almost all young children who are sent to boarding school suffer abandonment. A small child doesn’t understand the concept of boarding until it happens, so disbelief that their parents are really leaving them is common.

One man described how it wasn’t until he was standing on the steps of the school with his trunk, surrounded by total strangers, that he saw, with shock, the wheels of his parents’ car turning and realised that they really were leaving. Terror immediately gripped him; he felt totally alone in a strange world. Now in his mid-forties, he admitted this feeling for the first time, and with it came the outpouring of repressed grief.

It is a common story. Another boy knew he was going to board, but he too did not understand what it really meant. He was told to be brave, to not upset his mother – then he noticed, as she turned away, that she was crying. Left alone with the imperative not to express his emotions, he felt guilty because he had not prevented his mother’s upset. This is how children learn not to express or even recognise their own emotions as adults. The man who came to see me had never been able to cry since then.

From earliest infancy, parents give their children words for their feelings – it helps children to process emotion and their experiences. In the absence of this, and in the face of trauma, children have to shut down the capacity to feel – and an armoured personality develops.

However good a school is, a child will live without love. Abandonment may be unconsciously experienced as a betrayal – often as one enacted by their mother. As a result, in adult relationships, they may not trust their partner, because it is too risky to invest emotionally in another person.

More sinister was when the dormitory became a location of terror. In schools where bullying was not quashed, night-time could be like ‘Lord of the Flies’: lawless and unregulated

Bereavement is the second of the traumas many of these children experience. This has traditionally been called homesickness, a term that does not honour the depth of loss felt. It is profound, and children may be consumed with grief.

One man remembered how, as a boy aged six, he was told that he was too far away to go home for the holidays, so he was to be picked up by strangers, friends of his parents. He lost his parents and siblings and all that was familiar; family pets, his toys and his childhood bed.

For a child who is powerless to alter the situation, it is a major psychological rupture. They may feel guilt and shame, imagining they were sent away because they were not good enough. Trying to make sense of the feelings he experienced at the private prep school Maidwell Hall between the ages of eight and 13 in the 1970s, Spencer explains that he felt he had been sent to boarding school “because I’d fallen short as a son”.

The analogy with prison has been jokingly drawn by many, but it is serious. Children are issued with a uniform, told to conform to institutional rules relating to food, sleep and showering, and forbidden to leave unless “on parole”.

Captivity is often seen as the third trauma. One woman recounted to me how, aged 11, she and her friend walked out of their school. After being picked up by the police, they were shown a cell and told that if they ran away again, this is where they would stay.

Back at school, they were punished, and my patient learnt the lesson that she was captive. She did not try to leave again.

Do any of these experiences compare to the trauma of sexual abuse, also recounted by Spencer alongside tales of abandonment and childhood despair? In his memoir, he describes being sexually abused at age 11 by an assistant matron who was around the age of 19 and chose boys to have sex with each term, encouraging her “prey” to compete for her affection. Spencer perfectly encapsulates the confusion of a little boy longing for warmth and yet knowing this was not right.

Many of my male patients have told of how a teacher (usually male) would take them from their bed at night and give them “special attention”. Some were groomed in such a way that made a lonely child feel special. Deprived of love, and craving adult attention, they were easy prey for paedophiles – who were not uncommon in the unregulated system of private schools.

Spencer also details how John Porch, the “terrifying and sadistic” headteacher of Maidwell Hall from 1963 to 1978, inflicted brutal beatings, seemingly gaining sexual pleasure from the violence. Among my patients, sexual exploration and abuse often took place within their peer group as well.

Longing for physical affection, children turned to each other. Innocently seeking solace by getting into bed for a hug might turn sexual. Adults who experienced this form of abuse rarely identify it as such. It is often only when they have children of their own that they realise how unprotected they were.

More sinister was when the dormitory became a location of terror. In schools where bullying was not quashed, night-time could be like Lord of the Flies: lawless and unregulated. There was also abuse that was masked as friendship but bordered on coercive control, where a more powerful child would control their “friend”.

These childhood torments all have consequences in adult life. Spencer only confronted the effects of his time at the school in mid-life, but explains how signs of trauma manifested long before that. He believes that the emotional damage wrought by his time at the school in Northamptonshire had a devastating effect on his first two marriages.

Adults who were sexually abused may continue to have trouble sleeping, suffering from flashbacks or hypervigilance. Like Spencer, some lost their virginity early by paying a sex worker for their services.

For others, this continues into marriage, where sex is split off from love, so that a man with an apparently conventional life has a secret and separate sex life (with women or men). One such man proclaimed to me: “Women are for love and men are for sex.”

Research has also shown that adverse childhood experiences have a profound effect on the developing brain, affecting the development of neural pathways.

Disassociation is an unconscious mechanism that protects the vulnerable self and can become a kind of emotional armour. When, as adults, those who were damaged as children take positions of social power, they can become decision-makers with a lack of empathy.

Their experiences may also have an impact on the parenting of their own children. Boarding is a tradition passed down through the generations, so that parents who had to suppress their own feelings at these cruelties often perpetuate the problem by sending their own children away. Others are fiercely protective and keep them close. In the saddest of cases, some take their own lives.

When men like Spencer offer their stories, it is often claimed that the damage took place in the past and that schools have changed. In response to his book, a spokesperson from Maidwell Hall said that it was “sobering” to read about his experiences and that almost “every facet of school life has evolved significantly since the 1970s”, adding: “At the heart of the changes is the safeguarding of children and promotion of their welfare.”

This week, Mr Campbell paid tribute to the work of Edinburgh Academy rector Barry Welsh in creating a “completely different” environment at the school to the one he left. Mr Welsh reiterated his apology to pupils who suffered abuse and praised the “remarkable bravery” shown by those who gave evidence, adding: “Our commitment to facing up to the wrongs of the past remains unwavering.

It is the case that safeguarding, along with the employment of school counsellors, has made today’s schools safer, and there are those who certainly thrive. But there will still be countless others sent away at this tender age who will never recover from the loss of their home and family.

‘Boarding School Syndrome: The Psychological Trauma of the ‘Privileged’ Child’ by Joy Schaverien is published by Routledge

If you are a child and you need help because something has happened to you, you can call the NSPCC free of charge on 0800 1111. You can also call the NSPCC if you are an adult and you are worried about a child, on 0808 800 5000. The National Association for People Abused in Childhood (Napac) offers support for adults on 0808 801 0331

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks