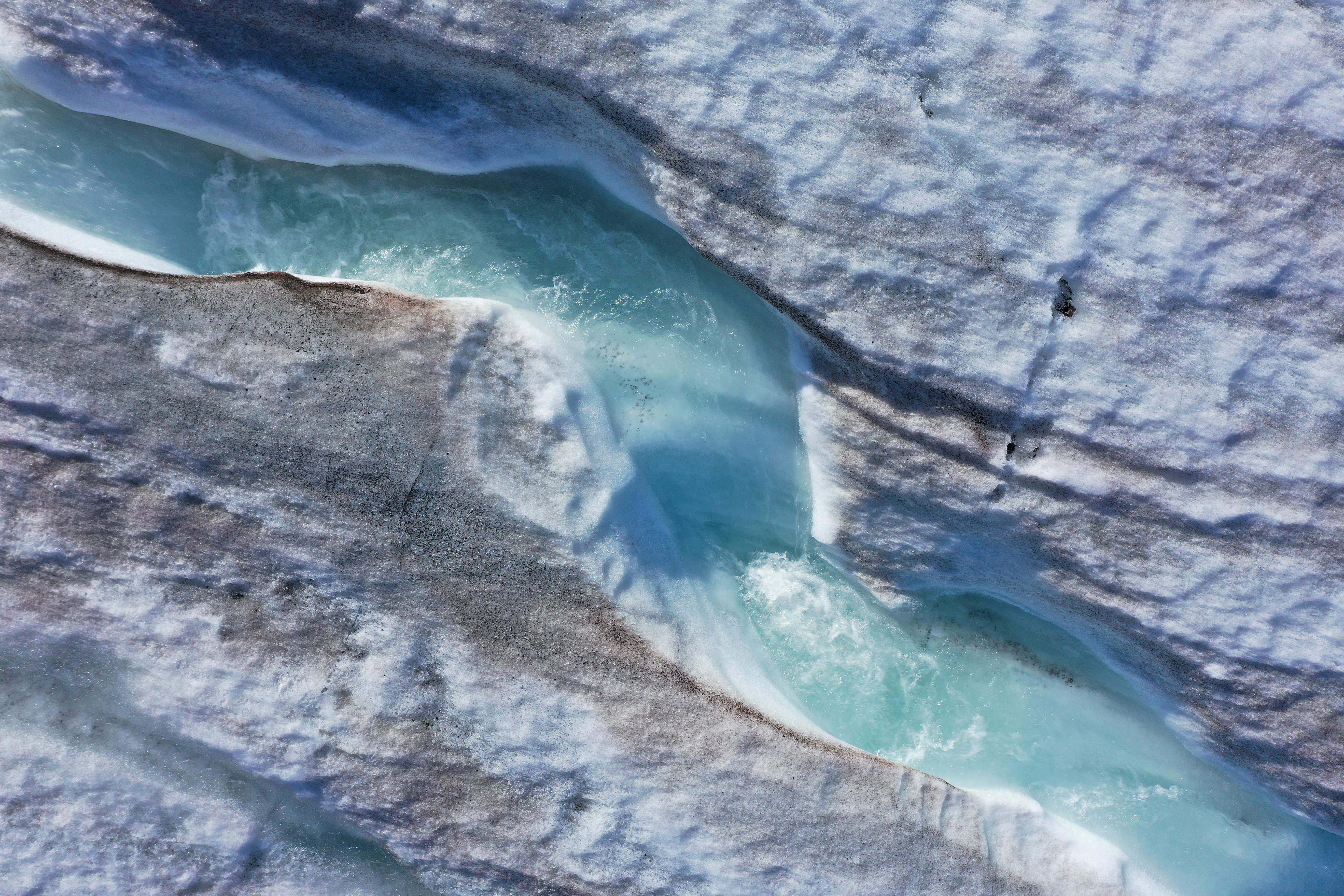

The Svalbard glaciers lost their protection in the 1980s and have been melting ever since

Glaciers are the canary down the mine when it comes to the climate crisis and our time is running out, warn Brice Noël and Michiel van den Broeke

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The archipelago of Svalbard, a land of ice and polar bears, is found midway between mainland Norway and the North Pole. Its capital Longyearbyen, on the main island of Spitsbergen, is the world’s most northerly city, some 800 miles inside the Arctic Circle.

Svalbard is also home to some of the Earth’s northernmost glaciers, which bury most of the archipelago’s surface under no less than 200 metres of thick ice. Taken together, Svalbard glaciers represent 6 per cent of the worldwide glacier area outside the large ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica – if they totally melted, they would raise the sea level by 1.7cm.

Because they are so far north, these glaciers are found at relatively low elevations, mostly below 450m above sea level compared to 800m or more elsewhere in the Arctic. Moreover, they are shaped like domes with steep sides and extensive flat interiors. These peculiar features make Svalbard glaciers highly vulnerable to climate warming, as we discovered in our research now published in Nature Communications.

Svalbard has a relatively dry climate, and each year the amount of meltwater exceeds the amount of snowfall that nourishes the glaciers. This was the case even before the climate started to warm in earnest. So how do these glaciers survive such unfavourable conditions?

Their secret is hidden below the surface, in a mantle of cold, compressed snow – called “firn” – that covers the glaciers’ interior. The porous firn layer can be up to 40m deep, and acts as a sponge that can store massive amounts of meltwater in its air pockets.

About half of all meltwater produced on Svalbard in the Arctic summer is stored and refrozen in the firn layer, preserving glacial mass by preventing the water from flowing into the ocean. When the glaciers stop melting in winter, the buffer capacity of the firn layer is replenished by the accumulation of fresh, fluffy snow, prepping it to store next summer’s wave of meltwater.

Being located at the margin of the rapidly declining sea ice cover in the Arctic Ocean, Svalbard is among the fastest warming regions on Earth. And this warming is testing the limits of the firn layer’s capacity to store meltwater.

Rising air temperature in the mid-1980s considerably increased the amount of water that was melting across the glaciers and rapidly filled the air pockets in the firn, progressively weakening its buffer capacity. To make matters worse, the firn layer retreated fast inland to reach the elevation of 450m – a critical point that left more than half of the archipelago’s glacier area unprotected.

The disappearance of firn leaves glaciers without their protective buffer, exposing the underlying dark bare ice at the surface. As dark ice absorbs more sunlight than the brighter firn, melt increased even further.

The rapid retreat of firn in the mid-1980s triggered a period of sustained mass loss, which has been confirmed by satellite observations. The loss of the meltwater buffer makes Svalbard glaciers highly vulnerable to a further temperature rise. In the warm summer of 2013, water reached the ocean from three-quarters of the glacier area, and mass loss more than doubled compared to previous years. In July 2020, Svalbard experienced record high temperatures once again. Some climatologists predict increases of up to 10℃ by the end of this century – if that happens, the archipelago’s glaciers could completely disappear in the next 400 years.

Further warming will completely reshape Svalbard’s climate, its landscape and its fragile ecosystems. Rain will progressively replace snowfall. Glaciers will trade their white firn mantle for dark ice. Open waters will invade fjords as sea ice and floating glacier tongues retreat. On land, receding glaciers will leave behind moraines and lakes as a reminiscence of a bygone glacial era. The landscape will start to resemble that of Iceland today, with bare rocks surrounded by grass, mosses and shrubs.

The retreating ice will allow increased human activity, including mining, farming and tourism, and further increase the pressure on the wildlife, including the polar bears. Already, polar bears are more frequently sighted on land as the rapid decline in sea ice has forced them to adapt and look for new hunting grounds, endangering both humans and the animals themselves.

Being located among the fastest warming regions on Earth, Svalbard glaciers are the canary in the coal mine. They can be seen as thermometers monitoring the devastating impacts of the climate crisis. It may not be too late to save part of Svalbard’s glacial landscape and the fragile ecosystems it supports, but time is quickly running out.Brice Noël is a post-doctoral researcher at the institute for marine and atmospheric research, Utrecht University. Michiel van den Broeke is a professor of polar meteorology and scientific director, at the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research, Utrecht University. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments