Stargazing in July: Don’t let the giant moon fool you

If you watch the full moon rising higher in the sky during the night this month, it seems to shrink, writes Nigel Henbest

Don’t be fooled by the moon illusion!

The full moon on 13 July will appear huge, like a vast hot-air balloon resting on the horizon – perfect for a romantic summer’s evening.

Its unusual size is partly real: the full moon this month is a supermoon, when our celestial companion is at its closest to the Earth and so it appears larger and brighter than the average full moon. But that’s not the whole story.

If you watch the full moon rising higher in the sky during the night, it seems to shrink. And that’s the unreal part, because the moon actually stays the same size. You can prove that by taking photos at regular intervals, and comparing the images. Or find something that just covers the moon when it’s on the horizon (like a pencil held at arm’s length), and the moon will stay the same width as the pencil whatever its height in the sky.

Astronomers have known about the “moon illusion” for two millennia. But, astonishingly, it’s still unexplained despite intensive research by astronomers, optical experts and neuroscientists.

Most researchers agree it’s something to do with the fact that the moon seems further away when it’s near the horizon. If you’re on a ship, you know instinctively that the horizon is very far off. On land, you compare the moon’s size to distant landmarks like houses or trees, and again that tells your mind the moon is very distant. And if the moon is far away, it must be big. Conversely, when the moon is high in the sky there are no depth cues, so the lunar disc seems smaller.

As an astronomer, I’ve known about the moon illusion most of my life. But the importance of the moon’s perceived distance hit me on a night-time drive in Australia. It was a dead-straight road, rising slightly towards a horizon that was only a kilometre or two away. I suddenly saw a light appear on the road where it crested the horizon – presumably from an oncoming vehicle.

Oddly enough, it wasn’t a pair of headlights; and the light grew steadily wider. My mind interpreted it as a coach with all the interior lights glowing, and no wider than the breadth of the road. Then I realised the top was curved: it was the moon rising, exactly in line with the highway. As soon as the truth struck me, the moon illusion kicked in. Knowing that this light was far off in the heavens, it suddenly appeared huge.

But scientists have found cues on the horizon are not the whole story. Brain-scanning experiments, using functional MRI show that the moon illusion isn’t created in the brain, as it struggles to reconcile conflicting evidence on the distance and size of the moon.

Instead, the moon illusion largely arise in our eyes. The retina isn’t just a simple camera, sending an accurate image to the brain for analysis. The cells of the retina are busy doing their own image-processing. According to the fMRI measurements, the nerve cells in the eye conclude that the moon on the horizon takes up a larger area of the retina than the moon high in the sky. So the brain is not creating the illusion; it’s just reporting faithfully what the retina is telling it.

So the moon illusion is likely to date way back to our remote past as living creatures, when eyes first developed – and long before the sophisticated human brain ever evolved. I’d love to know if other animals – especially nocturnal creatures like the cats that share my life – will also be treated to a giant summer moon this month.

What’s up

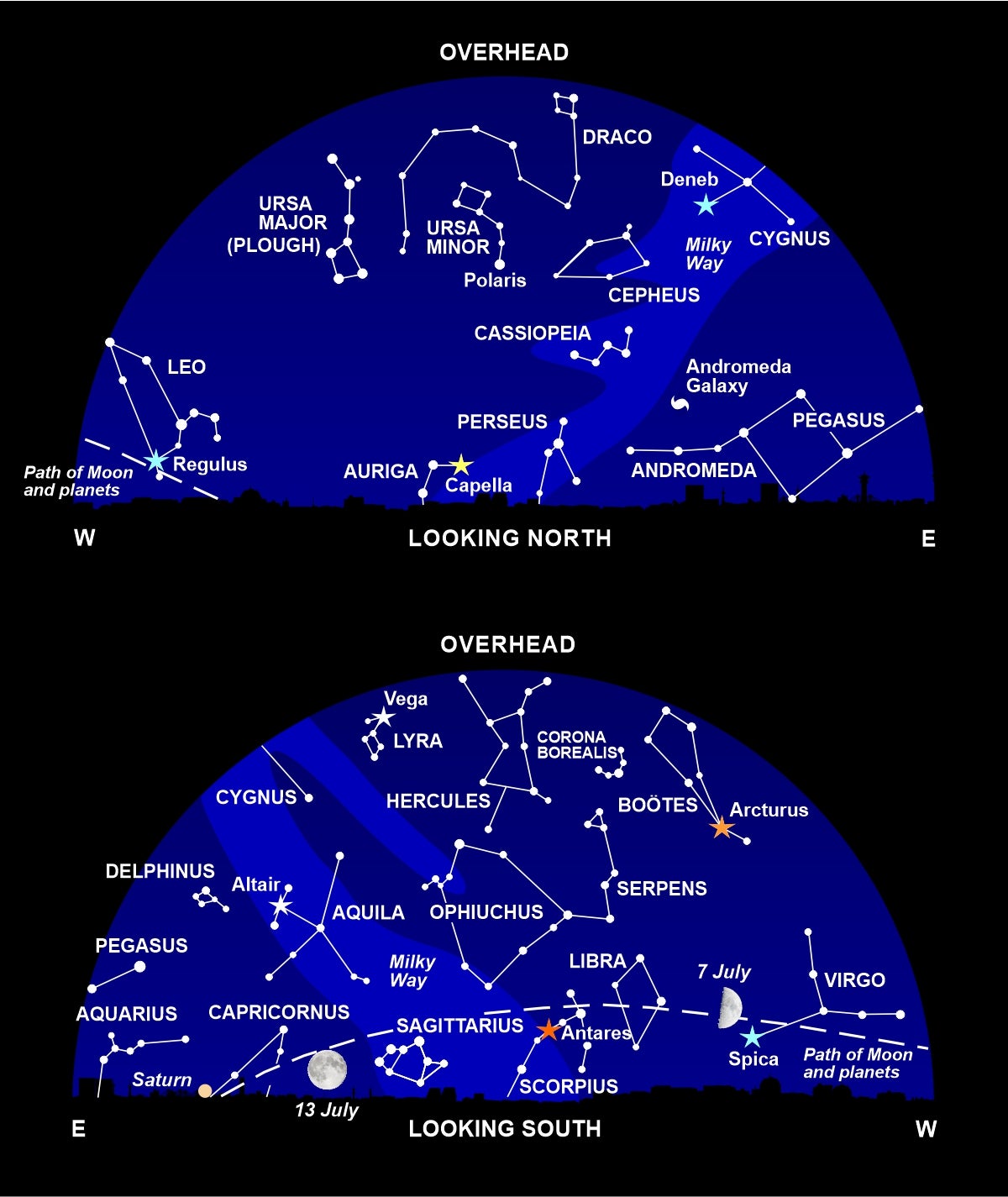

Look low in the south for our best annual view of two ancient and fascinating constellations that – alas! – are never well seen from northern latitudes. If you are travelling to more southern climes on holiday, find a spot away from light pollution and enjoy the sight of Scorpius and Sagittarius higher in the sky.

Dominating these two star patterns is the red giant star Antares. Binoculars will intensify its lurid colour, while a telescope reveals a fainter greenish companion star. Antares marks the heart of Scorpius (the Scorpion): three stars to the upper right demarcate its head; while a line of stars stretching down to the horizon make up its body and tail. From southern latitudes, you can see the tail curl up again, to end in two prominent stars marking its sting.

To the left of Scorpius, there’s a sprawling constellation whose brightest stars – to my eyes – form the shape of a teapot. The ancient Greeks, blessed with more imagination, saw these stars as a half-man, half-horse centaur, with a drawn bow, and called it the Archer (Sagittarius).

Both constellations are filled with pretty star clusters and nebulae: on a dark night, you’ll be well rewarded if you sweep around Scorpius and Sagittarius with binoculars or a small telescope.

After last month’s unusual line-up of all five naked-eye planets in the morning sky, in July we still have four of them in view. First to rise, around 11 pm, is distant Saturn. It’s followed at midnight by giant Jupiter, then an hour or so later by Mars. The red planet is currently far from the Earth, and no brighter than Saturn. Finally, brilliant Venus appears about 3 am.

Diary

7 July, 3.14am: first quarter moon near Spica

10 July: moon near Antares

13 July, 7.37pm: full moon, supermoon

15 July: moon near Saturn

19 July: moon near Jupiter

20 July, 3.18pm: last quarter moon

21 July before dawn: moon near Mars

22 July before dawn: moon near Mars

26 July before dawn: moon near Venus

27 July before dawn: moon near Venus

28 July, 6.55pm: new moon

‘Philip’s 2022 Stargazing’ (Philip’s £6.99) by Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks