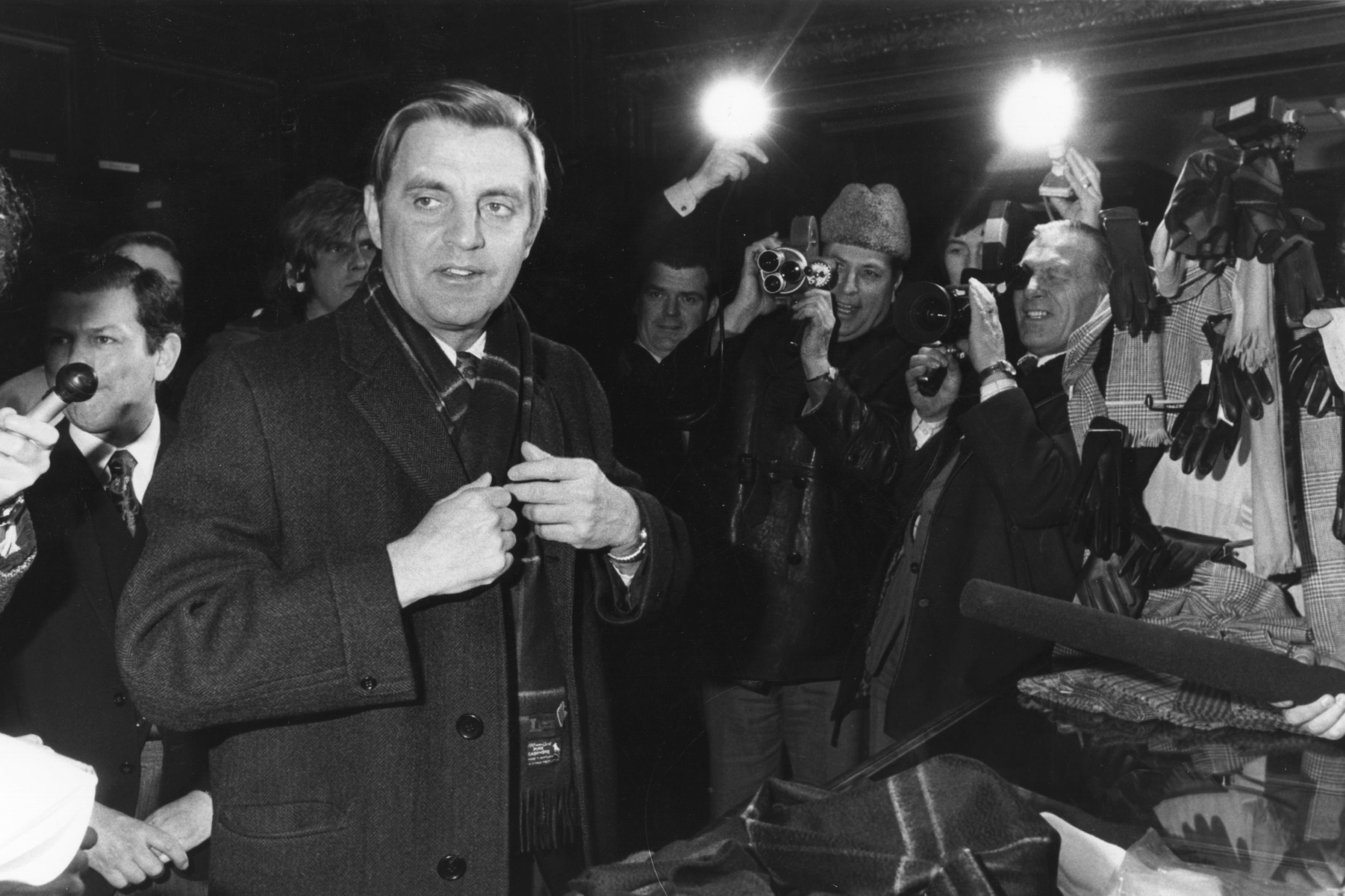

Walter Mondale: US vice president who quietly redefined his role

The Minnesotan was imbued with the civic values and social conscience of his traditionally Democratic state

Walter Mondale might have been on the wrong end of one of the biggest presidential election landslides in American history. But he will also be remembered as a vice president who quietly redefined his job, and as the first major-party candidate for the White House who chose a woman as his running mate. He was also one of the warmest, most decent and least self-important figures to set foot on America’s political stage.

Mondale, who has died at 93, was a Minnesotan, imbued with the civic values and social conscience of that traditionally Democratic state, bordering Canada and largely populated by emigrants from Scandinavia and northern Europe. Mondale himself was of Norwegian stock – the old family name was Mundal. His father was a Methodist minister, his mother an elementary-school teacher, and Mondale spent his childhood in the small towns of southern Minnesota.

Those were the years of the Great Depression, and inevitably the young man gravitated to the Democratic Party. His ambition was to be a lawyer, a goal he achieved in 1956 after graduating from the University of Minnesota Law School. By then he had also served two years in the military – not least to benefit from the post-war GI Bill, which paid for the law school course his parents could not afford. Most importantly, Mondale’s political career had already long been launched, under the aegis of another great Minnesotan liberal, Hubert Horatio Humphrey.

Humphrey and Mondale, mentor and protege, were unrelated. But they formed a de facto political dynasty that lasted more than half a century, and left an indelible mark on national politics along the way. Both were old-school liberals, their instincts harking back to Roosevelt and the New Deal. Mondale managed Humphrey’s first successful US Senate campaign in 1948; in 1964, when HHH was named vice president by Lyndon Johnson, Mondale was appointed by the governor to the vacant Senate seat.

Mondale won re-election in his own right in 1966 and then again in 1972. But his spell in the Senate ended after a dozen years when Jimmy Carter picked Mondale to be his running mate in 1976. After a race that grew steadily closer, the Democratic ticket narrowly defeated the Republican tandem of Gerald Ford and Bob Dole. Having been one of the youngest US senators in history, Mondale now became one of its younger vice presidents, aged barely 49 when sworn into office on 20 January 1977.

Until then the job had been mainly ceremonial and frequently detested by its occupants. Carter however gave Mondale broader new responsibilities, as spokesperson, troubleshooter and close counsellor. He was the first vice president to have an office in the west wing of the White House, and the first to have regular weekly lunches with his boss.

But this redefined relationship at the apex of American power was cut short by Ronald Reagan’s annihilation of Carter in November 1980. Briefly, Mondale went back to practising law, but his sights were already set on winning the biggest prize of all. Long before he formally declared his candidacy, he was his party’s acknowledged front-runner for 1984, with money, contacts and organisation that no rival could match.

For a while Gary Hart, the dashing and innovative young senator from Colorado, seemed to have a chance of upsetting the odds. But Hart ultimately faded. “Where’s the beef?” Mondale asked, pointing to his opponent’s failure to enunciate clear policies. At the 1984 convention in San Francisco, he was nominated on the first ballot – and his policies were all too clear. He would raise taxes, he told the convention, and so would the incumbent. “The only difference is, Ronald Reagan will not say so. I did.”

To the campaign, Mondale brought clear assets. He had resources and name recognition, and an obvious appeal to the party faithful. By the same token, though, he appeared to many as shopworn goods; as yesterday’s man, reminding Americans of a Carter presidency they were happy to forget.

Even so, he did take one groundbreaking decision, by choosing the New York congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate. Alas, much of the move’s positive impact quickly vanished amid questions over the finances of Ferraro’s husband.

But presidential elections are not won and lost by vice-presidential nominees, and Reagan vs Mondale was a mismatch. In private, the Democrat had a terrific sense of humour (he was an ardent fan of Monty Python) but on the campaign trail that autumn, levity was not his forte. Mondale’s stodgy style earned him the nickname of “Norwegian Wood”, after the Beatles song.

In a TV-driven election, his plodding emphasis on honesty and sincerity was easily trumped by the sunny optimism of “The Great Communicator”. Mondale came across as an old-fashioned machine politician, beholden to the unions and other interest groups. To be sure, he was the unabashed champion of the poor and downtrodden. But the vast majority of American voters consider themselves “middle class” – and in 1984 they went massively for Reagan.

A flicker of a chance beckoned after the first candidates’ debate, in which the president, then 73, seriously showed his age. But in the second debate, Reagan righted the ship, joking that he would not “make an issue” of his opponent’s youth and inexperience.

In reality, however justifiable the criticism of Mondale’s campaign, the likelihood of any Democrat winning that year was minimal. Reagan was judged to have boosted America’s standing abroad, while the economy was tangibly on the mend. Ferraro hardly sparkled, and many Democrats felt Lloyd Bentsen, the patrician Texan with wide appeal in the south, would have been a better choice. But even with George Washington on the ticket, the Democrats would probably still have lost.

On 6 November 1984, Mondale carried just his home state and the District of Columbia, and lost the electoral college by 525 votes to 13 – the heaviest defeat of any Democratic candidate ever, and eclipsed only by Franklin Roosevelt’s 523-8 trouncing of Republican Alf Landon in 1936.

After the election, Mondale returned to his former law practice in Minneapolis, but remained active within the party, chairing the newly created Democratic Institute for International Affairs. In 1993, there came an unlikely and seemingly final incarnation of Walter Mondale the public servant, as Bill Clinton’s first ambassador to Tokyo.

It proved an inspired choice. Mondale made a real effort to master the complexities of Japanese society and politics. Though not a Japanese speaker, he skilfully exploited his status as a former vice president and presidential candidate. On vexatious issues like Japan’s protectionist trade policies, and its reluctance to assume a military role remotely commensurate with its economic might, Mondale was chiding, but never impolite. He was also good at apologising – a valuable talent in Japan. By the time he left in 1997, “Monderu-san” was an almost revered figure.

And that seemed to be that. The retired ambassador again went home to his law practice, slipping comfortably into the role of party grandee and liberal icon, in an age when liberalism was often a tainted cause. But in October 2002 came a quite unexpected final call to arms.

By then, the Humphrey-Mondale mantle in Minnesota had passed to the progressive populist Paul Wellstone, who was defending Mondale’s old Senate seat. Less than a fortnight before that year’s midterm elections, Wellstone was killed in a plane crash. In desperation, the Democrats picked Mondale, at the age of 74, as an emergency replacement.

Reliably liberal Minnesota had changed, however. For younger suburban voters, his venerable name barely resonated, and on 5 November 2002, Mondale was narrowly defeated by the Republican Norm Coleman.

In 2008, Mondale endorsed Hillary Clinton for president, but switched his allegiance after Barack Obama sealed the nomination.

He married Joan (nee Adams) in 1955. She gained the nickname “Joan of Art” for her efforts during Mondale’s time in the White House to secure more government support for the arts.

The couple had two sons, Ted and William, and a daughter, Eleanor. Ted served in the Minnesota Senate and made an unsuccessful bid to be the Democratic nomination for governor in 1998. William served as an assistant attorney general. Eleanor, a broadcast journalist, died of brain cancer in 2011. Joan Mondale died in 2014 at 83.

Walter Frederick “Fritz” Mondale, lawyer, politician and diplomat, born 5 January 1928, died 19 April 2021

Rupert Cornwell died in 2017

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks