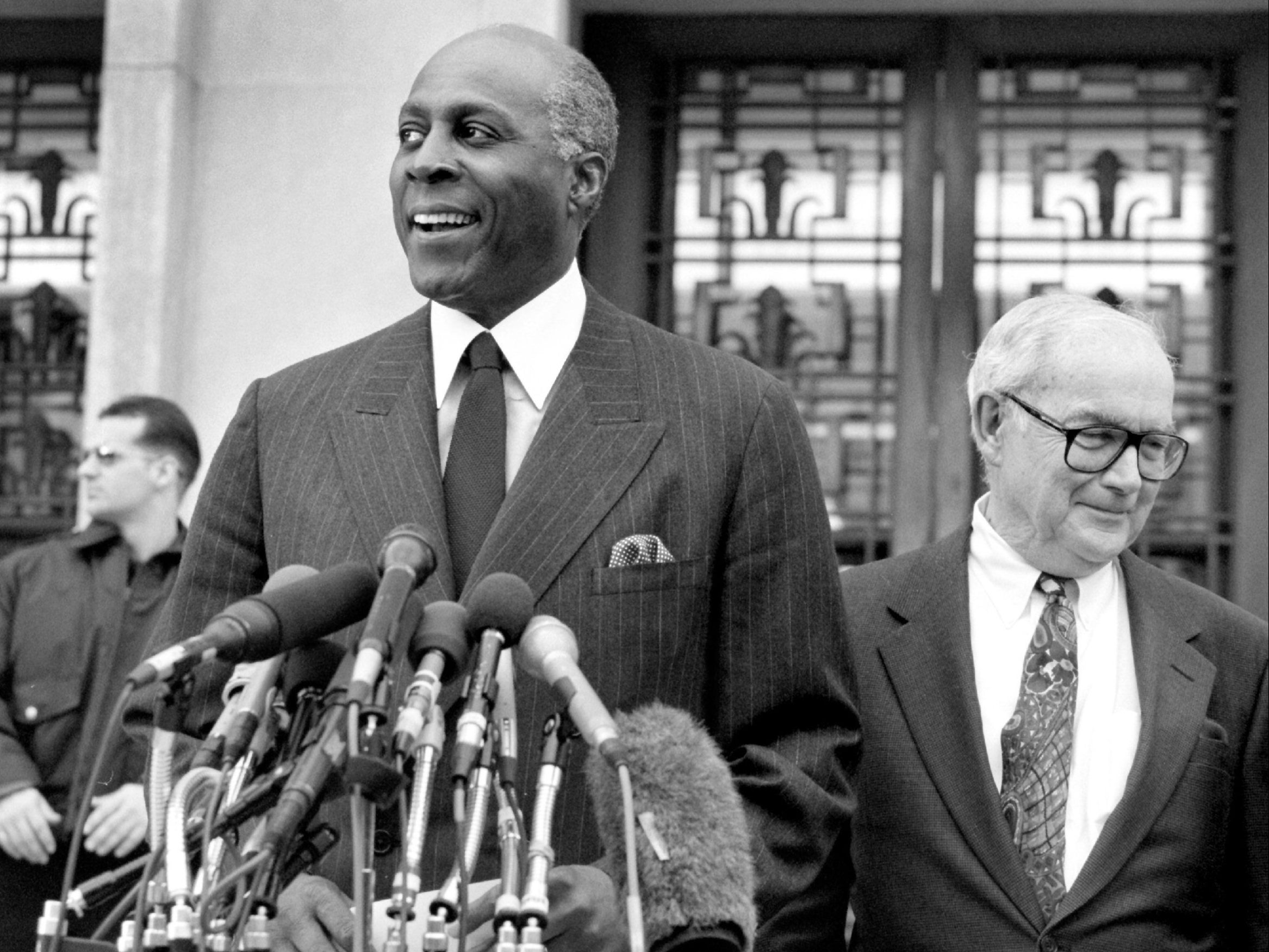

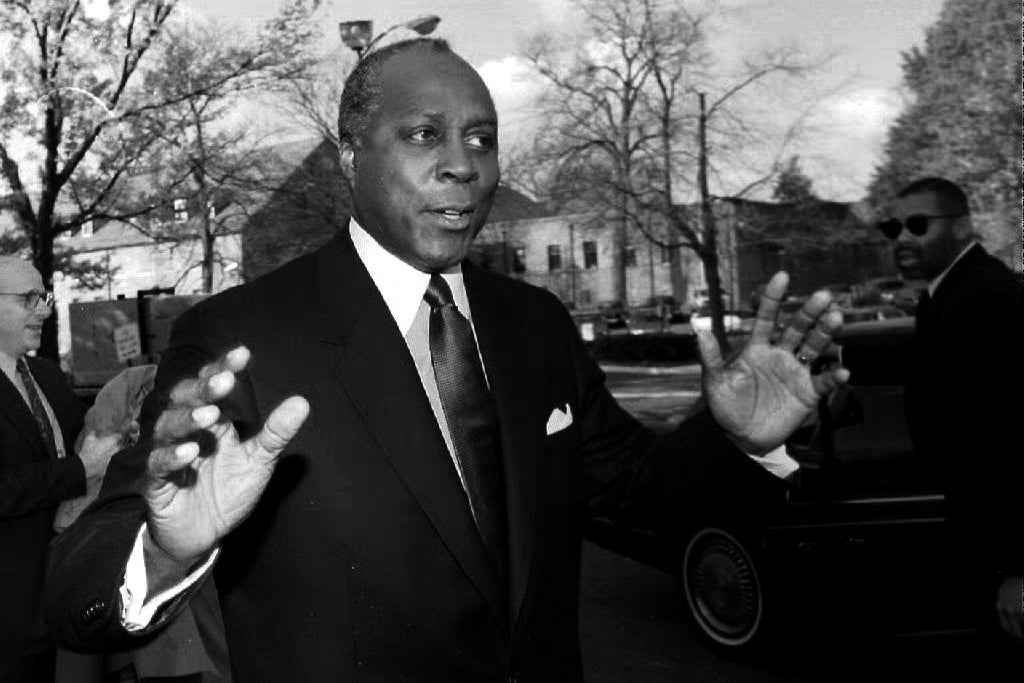

Vernon Jordan: Civil rights leader and adviser to Bill Clinton

The lawyer was the consummate DC power broker, reaching the peak of his quiet authority in the 1990s

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Vernon Jordan never held elective office, was never a member of the US cabinet and never even worked for his country’s federal government. He was a lawyer who rarely appeared in court, a corporate kingmaker who was not a registered lobbyist, a political strategist who did not direct a campaign.

Yet Jordan was, for years, one of the most influential figures in Washington. With a commanding presence, personal charm and an inviolable sense of discretion, Jordan had a rare combination of talents that made him the confidant of presidents, congressional leaders, business executives and civil rights figures.

He was the consummate Washington power broker, reaching the peak of his quiet authority during the 1990s, when he was, with the possible exception of Hillary Clinton, president Bill Clinton’s closest adviser. He had Clinton’s ear through two terms as president, including the most challenging moments, when Clinton faced an investigation and impeachment over a relationship with a White House intern.

“The last thing he’d ever do is betray a friendship,” Clinton said in 1996. “It’s good to have a friend like that.”

Jordan died on 1 March at his home in Washington DC. He was 85. The death was confirmed by his daughter, Vickee Jordan. She declined to state the cause.

Jordan brought a smooth manner and elegant style to dealmaking, anchored in his youth in a housing project in the US’s segregated south. He had the moral authority of a veteran of the civil rights movement – he nearly died in a 1980 shooting by a racially motivated would-be assassin – and was adept at navigating corporate boardrooms and golf course fairways, as well as gospel-filled churches.

There had been earlier generations of Washington insiders giving advice from the sidelines, including Tommy “the Cork” Corcoran, Bryce Harlow, Clark Clifford, Lloyd Cutler and Robert Strauss – Jordan’s mentor at the Akin Gump law firm. But one significant way in which Jordan differed from his predecessors was he was among the few African Americans at the top of Washington’s power structure.

It was a role he had cultivated for decades. As early as 1971, when he became executive director of the National Urban League, Jordan outlined an approach to bring the civil rights struggle to the highest levels of government and business.

“Black power will remain just a shout and a cry,” he said then, “unless it is channelled into a constructive effort to bring about black political power and to influence the established institutions of American politics.”

Instead of marching in the streets, Jordan marched towards the executive suite. He persuaded corporate leaders to hire black workers and support institutions – most notably the Urban League – that benefited African Americans. By the time Jordan came to Washington in 1981, his influence could be felt from Wall Street to Congress to the grassroots of the civil rights movement.

“I’m not a creature of the boardrooms,” he told People magazine that year. “I’ve got relatives on welfare. I’m a creature of the first public housing project for blacks ever built in America.”

Jordan was once under consideration to be commissioner of the National Football League and was rumoured as a possible attorney general or ambassador to Britain. But he never accepted a nomination for any position that would require Senate confirmation.

He sat on the boards of more than a dozen companies and wore custom-made shirts from Savile Row. For years, he spent Christmas Eve with Bill and Hillary Clinton, and presidents and billionaires came to his parties.

Yet the ways in which Jordan wielded his power remained something of a mystery. He had a magnetic quality, which DC delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton described to Vanity Fair as a “personality that seduces men and women differently, but nevertheless seduces”.

Jordan seldom left an official paper trail. People asked to discuss his clout in the capital often kept silent or sought his permission before responding.

“He learned what it was to be the quintessential insider. He was sort of a fixer,” Rice University historian Douglas Brinkley said. “I don’t think he was feared as much as he was a custodian of Washington gossip. He had an accumulation of dirt that could be used as a wedge against an opponent.”

Jordan made his presence felt in phone calls and cloakroom whispers, in casual clubhouse conversations and across the luncheon table. IBM sought Jordan’s advice when it needed a new chief executive; he set the wheels in motion for James Wolfensohn to be named president of the World Bank; he recommended people for jobs ranging from summer intern to secretary of state.

Jordan had an affability and charm – and a sometimes intimidating 6ft-4in physique – that put him at ease in any situation. He was often the only black person in the room. He was a Democrat, but he counted many Republicans among his friends.

“He has the ability and capacity to pick up the telephone almost any time and call almost any member of Congress, especially on the Democratic side of the aisle,” representative John Lewis said in 1992, when Jordan was co-chair of Clinton’s presidential transition team.

He cultivated political figures on the rise, long before they acquired a national profile. Jordan first met Hillary Clinton in 1969, the year she graduated from college, and Bill Clinton in 1973, when he returned to Arkansas from law school at Yale. He met Barack Obama when the future president was a state senator in Illinois.

He and Bill Clinton had a particularly warm rapport, with a shared southern heritage and an interest in golf. Jordan was among the first to suggest then-senator Al Gore as Clinton’s running mate in 1992. After Clinton was elected, Jordan vetted candidates for cabinet positions and the White House staff. When he later visited those officials, he always remembered to bring flowers for their administrative assistants.

“I have seen Vernon – too many times to count – help not just young people but any people,” Strauss told The Washington Post in 1998. “There are individuals in this country leading corporations and financial institutions and labouring in the vineyards because Vernon has been there to help and to make a few phone calls for them. That’s why people respect him.”

One topic often whispered about away from Jordan’s presence was what a 1992 Washington Post profile cited his “reputation as a lady-killer” – which he refused to discuss, except to say, “I like all kinds of people. And I’m not going to stop liking people.”

To Clinton, Jordan was a sounding board in good times and bad. He consoled the president after the 1993 suicide of deputy White House counsel Vincent Foster and after commerce secretary Ron Brown was killed in a plane crash in 1996.

The relationship between the president and his counsellor faced its most severe test in 1998, when Clinton was being investigated for an alleged relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Jordan reportedly arranged to hire a lawyer for Lewinsky and find her a job with Revlon, one of the companies of which he was a board member. (The job offer was rescinded amid the turmoil.)

Jordan made five appearances before a grand jury during the independent counsel investigation of Clinton led by Kenneth Starr. He answered questions during a House of Representatives inquiry that led to Clinton’s impeachment.

As Republican opponents accused Jordan of conspiring with Clinton to obstruct justice, he did not lose his composure. He never discussed the scandal in public, even after Clinton was acquitted by the Senate.

Jordan was so closely identified with Clinton that, as he later told the Los Angeles Times, “People look at me and believe that I was born January 20 1993,” the day Clinton took office as president. “That is not true. My life was defined long before that.”

Vernon Eulion Jordan Jr was born on 15 August 1935 in Atlanta. His father was a postal worker on a military base.

Jordan attended segregated schools, but he also was exposed to Atlanta’s elite white society while working for his mother’s successful catering business. At his mother’s urging, he left the south for college, attending DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana. He organised voter registration drives for black residents of the region and became prominent in campus government and oratory.

During his summer breaks, he returned to Atlanta, working as a chauffeur and waiter for an ageing Robert Maddox, who had been the city’s mayor from 1909 to 1911. Jordan sometimes read the books in Maddox’s voluminous library, prompting a rebuke from his boss.

Even after Jordan received permission to use the library, the former mayor told his family at dinner that he had an announcement to make: “Vernon can read.” Jordan never forgot the incident and used the backhanded comment as the title of his 2001 memoir.

After graduating in 1957 from DePauw, where he was the only black member of his class, Jordan entered law school at Howard University in Washington. He graduated in 1960, then joined an Atlanta firm led by a prominent African American lawyer, Donald Hollowell.

The firm sued the University of Georgia on behalf of Charlayne Hunter, who become one of the institution’s first two black undergraduates in 1961. Jordan escorted her to class through jeering crowds.

Soon afterwards, Jordan became Georgia’s field secretary for the NAACP and led boycotts of stores that refused to hire black workers. He moved to Arkansas in 1964 and coordinated voter registration efforts that added 2 million black voters to rolls across the US south.

By 1969, Jordan was a fellow at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, and the next year he became executive director of the United Negro College Fund. When Whitney Young Jr, executive director of the National Urban League, drowned on a visit to Nigeria in 1971, Jordan was chosen as his successor.

He oversaw a budget of $100m and travelled extensively to raise funds from corporate leaders to support job training, early childhood education and other programmes aimed at improving black life in the United States. He joined the boards of blue-chip companies including American Express, Xerox, Dow Jones & Co, Union Carbide and RJR Nabisco, and used his access to executives to encourage major companies to hire women and members of minority groups.

Early on the morning of 29 May 1980, after addressing an Urban League gathering, Jordan was shot in the back with a high-powered rifle after exiting a car in a parking lot in Fort Wayne, Indiana. He was rushed to a hospital, where doctors managed to close a wound the size of a fist. Jordan noted that the surgeon, internist and anesthesiologist who treated him in Fort Wayne were African American.

“Now what that suggests,” he said, “is that there has been some progress.”

President Jimmy Carter and senator Edward Kennedy went to Fort Wayne to see Jordan. After he was transferred to a hospital in New York, he was visited by Ronald Reagan, then-Republican presidential candidate, and a host of corporate titans as well as religious and civil rights leaders.

Indiana authorities arrested Joseph Paul Franklin in connection with the shooting. He was previously charged but never tried for the 1978 shooting that left Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt paralysed. He had a history of racial violence, including shooting at mixed-race couples. (Jordan had stepped out of a car driven by a white woman.)

At trial, Franklin was found not guilty of violating Jordan’s civil rights. Years later, Franklin confessed to the shooting; after having been convicted of eight and linked to as many as 20 murders around the country, he was executed in Missouri in 2013.

During his 98-day hospitalisation, Jordan reassessed his life. With the Urban League facing a chilly political climate under Reagan and a newly elected Republican Congress, Jordan moved to Washington as a senior partner with Akin Gump.

He was sometimes described as a “superlawyer,” but his role at the law firm and lobbying shop resisted easy definition. He was not a registered lobbyist and did not argue cases in court.

“If you ever see me in the library here, tap me on the shoulder,” he reportedly told a colleague. “For you will know that I am lost.”

As the Clinton presidency was coming to an end in 2000, Jordan took a senior position at the New York investment banking firm of Lazard Frères, for a reported salary of $5m a year.

He retained his position at Akin Gump – “I’m there every Friday,” he said – and continued to be a presence in Washington.

Jordan’s first wife, the former Shirley Yarbrough, died of multiple sclerosis in 1985, after 26 years of marriage. The next year, he married Ann Dibble Cook, a onetime professor of social work at the University of Chicago. In addition to his wife, survivors include a daughter from his first marriage, Vickee Jordan Adams.

During the 2008 presidential election, he supported Hillary Clinton over Obama, saying, “I’m too old to trade friendship for race.”

Yet Obama joined Jordan on the golf course and clearly recognised his eminence. Each year, as business moguls and political luminaries descended on Washington for the annual dinner of the Alfalfa Club, there was one invitation that was even more exclusive: brunch at Jordan’s house. Warren Buffett, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos (Amazon founder and owner of The Washington Post) and congressional leaders were likely to be there, rubbing elbows and sampling the omelettes.

Even when Obama skipped the Alfalfa Club’s white-tie dinner, he made time to show up at Jordan’s brunch.

Vernon Jordan, lawyer and civil rights leader, born 15 August 1935, died 1 March 2021

© The Washington Post